I. Introduction

In the 21st century competition in science and technology, human capital has become the most critical resource. In particular, the movement of outstanding researchers in cutting-edge fields is drawing significant attention as a major factor in determining national competitiveness. Chinese researchers based in the United States occupy a unique place in this ecosystem as researchers who deeply understand both the United States’ state-of-the-art research environment and China’s rapidly evolving innovation ecosystem. Their movements have become a core factor shaping the trajectory of the U.S.-China rivalry in science and technology.

This paper analyzes the structure and impact of this human capital migration from two perspectives: the “push factors” whereby policy environment changes under the second Trump administration encourage Chinese researchers to return home, and the “pull factors” strategically deployed by the Chinese government. Furthermore, based on the latest Nature Index, we examine the already emerging shifts in the global landscape of science and technology and consider future prospects and policy implications for various nations.

II. “Push Factors” Encouraging the Return of Chinese Researchers

To understand the trend of Chinese researchers affiliated with U.S. universities and research institutions returning to China, it is first necessary to analyze the “push factors” that are driving them out of the United States. Under the second Trump administration, the combination of a significant reduction in science research funding, the continuation of hardline policies toward China, and the intensification of discriminatory treatment of Chinese researchers have led many of them to seriously consider whether they should leave the United States.

1. Reductions in Scientific Research Funding and the Deterioration of the Research Environments

The deterioration of the research environment in the United States is at the core of the “push factors” encouraging the return of Chinese researchers. In particular, reductions in scientific research funding are leading to institutional instability and accelerating the outflow of researchers.

In the second Trump administration, the funding based on laws enacted under the Biden administration such as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), as well as the CHIPS and Science Act, which support science, technology, and economic competitiveness, have seen successive freezes and reviews (Note 1). Meanwhile, proposals for significant budget cuts and grant suspensions have been presented for major scientific institutions such as the National Science Foundation (NSF) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), raising concerns about increased uncertainty and reduced transparency in research administration (Note 2).

These developments are leading to grant reductions and the downsizing of research infrastructures across a wide range of fields including public health and medical research, climate science, clean energy, education and social sciences, and humanities research. Furthermore, this could result in a decline in the number of papers published and research results obtained, as well as structural weakening such as increased employment instability for early-career researchers, graduate students, and postdocs.

A survey conducted in March 2025 by the British scientific journal Nature targeting over 1,600 researchers residing in the United States found that approximately 75% responded that they were “considering leaving the United States due to the deterioration of the research environment under the Trump administration(Note 3) .” This figure vividly reflects the profound sense of crisis within the research community.

2. Escalation of U.S.-China Tensions

The recent deepening of tensions between the United States and China in the field of science and technology has also led to increased pressure on Chinese researchers.

The "China Initiative," introduced in 2018 under the first Trump administration, was originally intended to counter economic espionage by China, but in practice the focus was on issues such as failures to disclose researchers’ funding sources and relationships with overseas institutions, and nearly 90% of the defendants prosecuted under this initiative were of Chinese descent (Note 4). Although this policy ended under the Biden administration, its aftereffects persist.

The revision of the U.S.-China Science and Technology Agreement (STA), which defines the framework for scientific cooperation between the two nations, has also cast a shadow over personnel exchanges. While the 2024 agreement extended the STA for five years, cutting-edge fields directly tied to national security—such as artificial intelligence (AI), quantum technology, and semiconductors—were excluded from cooperation. Collaboration is now limited to basic sciences like meteorology and geology. As a result, a “decoupling” between the U.S. and China in the scientific sphere has become unavoidable, and the opportunities for Chinese researchers to thrive within this framework have been significantly reduced.

3. Tightening Constraints in U.S. Immigration and Visa Policies

U.S. immigration and visa policies are also imposing stricter restrictions on Chinese researchers. For graduate students and researchers in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) fields, visa durations are being shortened, and rejection rates are rising, undermining the stability of their research activities and long-term stays.

Moreover, under the second Trump administration, for new H-1B visa applications, a $100,000 application fee has been newly introduced (Note 5). As a result, companies’ hiring costs are rising substantially, and it is expected that hiring foreign researchers will become more difficult, especially for startups, universities and research institutions.

III. “Pull Factors” Encouraging the Return Home of Chinese Researchers

While the United States’ “push factors” are driving Chinese researchers away, China is also strengthening a national strategy to make itself a more attractive host. Specifically, measures to enhance incentives have been implemented not only in terms of economic incentives, but also in multiple dimensions―such as appealing to cultural identity, enhancing social status, fostering a sense of participation in national development, which have created “pull factors” that encourage researchers to return to their home country.

1. Economic Factors

Since the launch of the China’s Thousand Talents Plan in 2008, the Chinese government has positioned the recruitment of overseas human capital as a national strategy and has offered special economic incentives (Note 6). Local governments have also raced to roll out their own support programs—such as Beijing Overseas Talent Aggregation Project, Shanghai Pujiang Talents Program, and Shenzhen Overseas High Level Talent (Peacock Plan) Project— engaging in a coordinated central–local competition to attract talent.

Large-scale investment in the research environment has also become a major incentive for researchers. In 2024, China’s research and development (R&D) spending reached 3.61 trillion Chinese Yuan, amounting to a 2.7% share of GDP (Note 7). As a result of this investment, world-class research facilities have been established, and the research environments at the Chinese Academy of Sciences and major universities have been significantly improved. In industry as well, companies such as Huawei, Alibaba, and Tencent have established large-scale research labs, and high-paying positions in AI, biotechnology, and new energy fields are rapidly increasing.

Also, as national policy, China is promoting “mass entrepreneurship and innovation” to boost startups and improve the startup environment. Regulatory reforms have advanced, such as the digitalization of company registration procedures and the acceleration of business license granting procedures, and financing channels have been enhanced through the growth of the venture capital market and the establishment of markets for emerging companies, such as the Shanghai Stock Exchange Science and Technology Innovation (STAR) Board Market. Startup support facilities and incubators have been established across the country, and tax incentives for startups as well as tax credits for research and development expenses have been introduced. Furthermore, digital infrastructure such as electronic payment systems, cloud services, and e-commerce platforms has advanced significantly, creating an environment in which entrepreneurs can more easily start businesses.

Moreover, on October 1, 2025, China introduced a new “K visa,” launching a system that offers long-term residency and multiple-entry visas without a sponsor for young professionals and overseas researchers in STEM fields (Note 8). This system simplifies procedures compared to traditional work visas and provides a framework that can be flexibly utilized for research and entrepreneurship. As a result of these various measures, research and startup opportunities within China are expected to expand both for Chinese-origin individuals who have already acquired foreign citizenship and for overseas talent.

2. Social Factors

A sense of belonging within Chinese culture and a Chinese identity are among the factors that encourage many researchers to return home. After extended periods living overseas, family connections and interest in conducting research in their homeland often resurface. Regarding children’s education, options have increased significantly with the expansion of international schools and the establishment of Chinese campuses by overseas universities (Note 9).

Aspects related to social status should not be overlooked. Returning researchers often receive a certain level of recognition and attention domestically, and they may be given opportunities to engage not only in academia but also in industry and policymaking. As a result, they have increasing opportunities to apply their expertise to improving society.

In addition, the opportunity to participate in national projects and policies is another motivation for returning. National strategies such as “Building a Strong Country in Science and Technology” and “Made in China 2025” are creating platforms on which they can leverage the experience accumulated overseas.

IV. Reverse Brain Drain from the United States to China

As a combined result of both the “push” and “pull” factors analyzed in the previous section, China has been undergoing a historic shift from “brain drain” to “brain gain” since the beginning of the 21st century. This change is not merely a quantitative shift: it is also accompanied by qualitative improvements in the talent returning to China.

1. Return Home of Chinese International Students

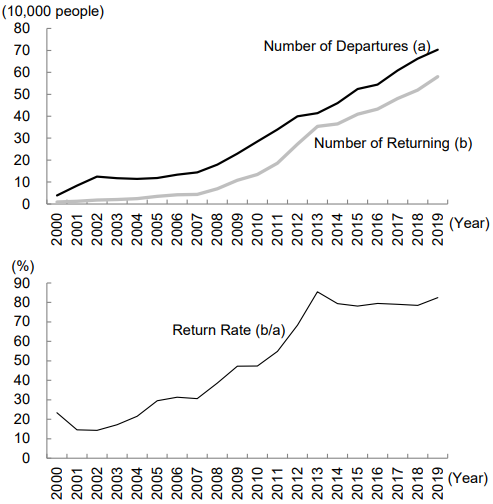

Even before the advent of the Trump administration, the return rate of Chinese international students had been on an upward trend since the early 2000s. According to statistics from China’s Ministry of Education, while 83,973 students left China to study abroad in 2001, only 12,243 returned, resulting in a return rate of just 14.6%. However, against the backdrop of China’s rapid economic growth, both the number of students going abroad continued to rise and the return rate also gradually increased. By 2019, the number of students going abroad had increased to 703,500, while the number returning reached 580,300, raising the return rate to 82.5% (Figure 1).

Although these statistics have not been released since 2020, the upward trend in return rates is believed to be continuing. Partly due to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of returning students from overseas exceeded the number of departing students for the first time in 2020, and it has been reported that the gap widened further in 2021 (Note 10).

2. The Accelerating Return of Researchers

Amid U.S.-China tensions, the return of Chinese researchers has also accelerated. According to a survey conducted by the Asian American Scholar Forum from December 2021 to March 2022 targeting Chinese scientists and engineers in the United States, 61% are considering leaving the United States. As reasons, 35% cited “not being welcomed in the U.S. as researchers,” 72% cited “not feeling safe conducting research in the U.S.,” 42% cited “being afraid to conduct research activities in the U.S.,” and 65% cited “concerns about joint research with China.” In addition, against the backdrop of restrictions on the admission of Chinese students, 86% stated that “recruiting outstanding students has become more difficult than before (Note 11).”

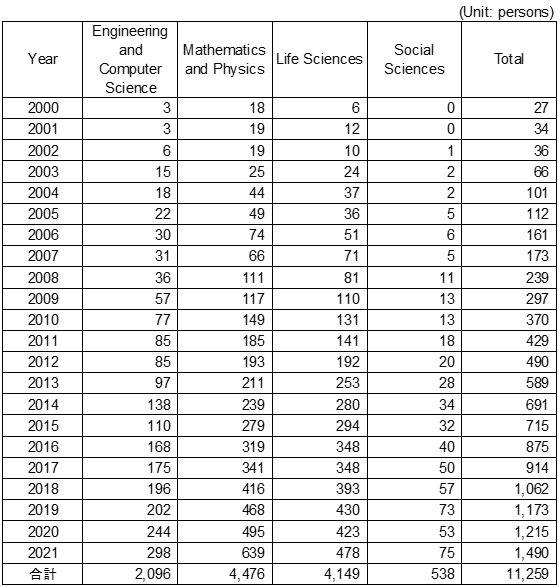

The cumulative number of returning Chinese scientists (including social scientists) reached 11,259 between 2000–2021. Of these, 4,940 people, or 43.9%, returned between 2018–2021 (Figure 2). Among them are not only established academic authorities approaching retirement but also many up-and-coming researchers.

Source: Compiled by the author based on Xie, Yu, Xihong Lin, Ju Li, Qian He, and Junming Huang, “Caught in the Crossfire: Fears of Chinese-American Scientists,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Volume 120, Issue 27, June 2023.

3. Contributions of Returning Researchers to Science and Technology

Since the founding of the People’s Republic of China, especially under the modernization policies propelled by the Reform and Opening-up policy beginning in 1978, the role of Chinese researchers returning from overseas has expanded significantly. While this was limited to the military technology sector during the Mao Zedong era, as reform and opening progressed, it came to encompass basic science, applied research, and industrial technology (recent cases are discussed below. For contributions by returning scientists during the Mao era, see BOX1).

Returning researchers have linked China’s research community to international academic networks by facilitating joint research and human capital exchanges with Europe, the United States, and elsewhere, thereby enhancing the ability to disseminate work through co-authored papers and international conferences, while also raising the next generation to international standards through education and mentoring at universities and research institutions. They have also contributed to areas such as building research infrastructure, fundraising, and introducing evaluation systems, supporting the construction of a long-term innovation foundation. Furthermore, they have promoted the commercialization and industrial application of technology, making significant contributions to the establishment of startups and the industrialization of research outcomes.

V. Case Studies of Returning Researchers in Basic Science

In basic scientific fields such as mathematics, physics, chemistry and materials engineering, and life sciences, top-tier Chinese researchers have continuously returned to the country (Note 12).

1. Mathematics (YAU Shing-Tung)

Among the mathematicians who have returned, Shing-Tung Yau's contributions are particularly noteworthy. Born in Guangdong Province in 1949, Yau moved to Hong Kong in childhood, studied at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and earned his Ph.D. at the University of California, Berkeley. Subsequently, he taught at institutions such as Stanford University, Princeton University, and Harvard University, and in 1982 he received the Fields Medal, achieving global recognition for his work on the Calabi–Yau manifolds in differential geometry. Since his first visit to China in 1979, Yau has continuously supported the development of China’s mathematics education and research environment, and in 2022 he formally returned as a professor at Tsinghua University. Through his dedicated efforts, the modernization of China’s mathematics education system, the establishment of research environments to international standards, and the cultivation of young mathematicians have all advanced significantly.

2. Physics (YANG Chen-Ning, PAN Jianwei)

The return of Chen-Ning Yang, the 1957 Nobel Prize laureate in Physics, made a significant contribution to the development of physics in the country. Born in 1922, Yang specialized in theoretical and particle physics, earned his Ph.D. at the University of Chicago after graduating from the National Southwestern Associated University, and subsequently conducted research and teaching at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton and at the Stony Brook University, the State University of New York (SUNY). In 2003, he joined Tsinghua University, where he devoted himself to nurturing young personnel and promoting international research exchange.

Pan Jianwei, born in 1970, is noted for his contributions in the fields of quantum physics and quantum communication. He earned his Ph.D. at the University of Vienna after graduating from the University of Science and Technology of China, and following research experience at the Heidelberg University, moved to the University of Science and Technology of China in 2001. The research team he leads has been at the global forefront of quantum communication technologies, and in 2016 they successfully launched the world’s first quantum communication satellite, Micius, propelling China’s quantum technology research to the global cutting edge.

3. Chemistry and Materials Engineering (WANG Zhonglin, GAO Huajian)

Nanotechnology specialist, Wang Zhonglin was born in 1961, graduated from the Northwest Telecommunication Engineering Institute (now Xidian University), and obtained his Ph.D. at the Arizona State University. He then served for many years as a professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology, establishing the foundations of nanogenerator technology. In 2024, he became the director of the Beijing Institute of Nanoenergy and Nanosystems, Chinese Academy of Sciences, aiming to advance the practical applications of nanogenerator technology, especially in energy harvesting technologies.

Gao Huajian, born in 1963, has also made significant contributions in the fields of material mechanics and nano mechanics. He earned his Ph.D. from Harvard University after graduating from Xi'an Jiaotong University, and conducted research and teaching at Stanford University, the Max Planck Institute for Metals Research, and Brown University. He joined Tsinghua University in 2024 and has been promoting the strengthening of the foundation for new materials development and promoting research at the interface between biomaterials and artificial materials.

4. Life Sciences (SHI Yigong, FU Xiangdong)

Shi Yigong, a specialist in structural biology and cell biology, was born in 1967. After graduating from Tsinghua University, he earned his Ph.D. at Johns Hopkins University and served as a professor in the Department of Molecular Biology at Princeton University, achieving outstanding results in structural studies of the RNA splicing mechanism. He joined Tsinghua University in 2008 and became the president of Westlake University, China’s first research-focused private university, in 2018. He has elevated China’s structural biology research to a world-class level and, through Westlake University, is building a new model for research universities.

Born in 1963, Fu Xiangdong has also played a significant role in the field of RNA biology. He specializes in RNA biology and gene regulation, served for many years as a professor at the University of California, San Diego, and established an international standing in RNA splicing research. In 2023, he joined Westlake University and now serves as Chair Professor of RNA Biology and Regenerative Medicine at the School of Life Sciences.

VI. Case Studies of Returning Researchers in the Applied and Industrial Technologies Field

In the field of applied and industrial technologies, the returning researchers are particularly notable in cutting-edge areas such as AI, semiconductor technology, new energy technologies, and IT platforms.

1. Artificial Intelligence (Andrew YAO)

Born in Shanghai in 1946 and moving to Taiwan in his childhood, Andrew Yao (Yao Qizhi) has made significant contributions to the development of artificial intelligence (AI) in China. He studied physics at National Taiwan University and earned his Ph.D. at Harvard University, then continued his research at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Stanford University, and Princeton University. Recognized for his achievements in computational theory, he received the Turing Award in 2000. After moving to Tsinghua University in 2004, he established the Institute for Interdisciplinary Information Sciences (IIIS), introduced first-class computer science education, and as the inaugural dean of the College of AI, he helped build the foundation for cultivating AI human resources in China.

2. Semiconductor Technology (Richard CHANG)

Born in Nanjing in 1948 and raised in Taiwan, Richard Chang (Zhang Rujing) is known as the “Father of China’s Semiconductor Industry.” He studied mechanical engineering at National Taiwan University, earned a master’s degree at the State University of New York at Buffalo, and a Ph.D. at Southern Methodist University. He then gained experience at Texas Instruments and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC). In 2000, he established Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC) in Shanghai, which became China’s largest semiconductor foundry, playing a crucial role in laying the foundation of China’s semiconductor industry. Thanks to Zhang’s efforts, China acquired independent technological development capabilities in semiconductor manufacturing and was able to enhance the industry’s autonomy.

3. New Energy Technologies (SHI Zhengrong)

Born in 1963, Shi Zhengrong played a pioneering role in the development of China’s new energy industry. After graduating from Jilin University in 1983, he engaged in optical research at a Chinese government-affiliated research institute. Subsequently, he studied in Australia, earned a Ph.D. in Electronic Engineering at the University of New South Wales, and gained experience at the university-spun-out venture Pacific Solar. Returning to China in 2001, he founded Wuxi Suntech Power, which grew into the world’s largest solar cell manufacturer. Although Suntech Power went bankrupt in 2013, the talent and technology cultivated at the company became a strong force, propelling the growth of China’s photovoltaic industry.

4. IT Platforms (Robin LI, WANG Xing, Colin HUANG)

In the IT platform field, returning entrepreneurs have driven the development of China’s digital industry. Three representative figures are Robin Li (Li Yanhong), Wang Xing, and Colin Huang (Huang Zheng).

Born in 1968, Robin Li graduated from the Department of Information Management at Peking University, went to the United States in 1991, and obtained a master’s degree in computer science from the University at Buffalo, SUNY. After working at a subsidiary of Dow Jones in the United States, he joined Infoseek in 1997 to develop search engines. Retuning to China in 2000, he founded Baidu, building the country’s largest search engine. Beyond search, Baidu expanded into AI, autonomous driving, and cloud computing, making major contributions to the foundational digital ecosystem in China.

Born in 1979, Wang Xing graduated from the Department of Electronic Engineering at Tsinghua University and then studied at the University of Delaware in the United States, where he obtained a master's degree in computer engineering. He returned to China in 2003 and launched several internet ventures before founding Meituan in 2010. Meituan started as a platform specializing in group-buying services which has grown into an integrated platform offereing a wide range of life-related services, including food delivery, mobility, hotel and travel booking, and movie ticket reservations.

Born in 1980, Colin Huang graduated from Zhejiang University and then earned a master's degree in computer science from the University of Wisconsin–Madison in the United States. After working at Google, he returned to China in 2007, started multiple ventures, and established Pinduoduo in 2015. Leveraging a social e-commerce model that combines group buying with social networking elements, Pinduoduo rapidly attracted price-sensitive consumers in rural areas and small and medium-sized cities. Furthermore, through its platform “Temu,” it has expanded into the U.S. and European markets, leading the internationalization of Chinese e-commerce.

VII. The Growing Possibility of U.S.–China Reversal

Driven by the contributions of returning researchers and the Chinese government’s strategic investments, a fundamental change is occurring in the traditional U.S.-centric international framework of science and technology. As indicated by international research evaluation metrics such as the Nature Index, China is showing signs of matching or surpassing the United States in many fields, making the possibility of a historic reversal in the global science and technology landscape increasingly realistic.

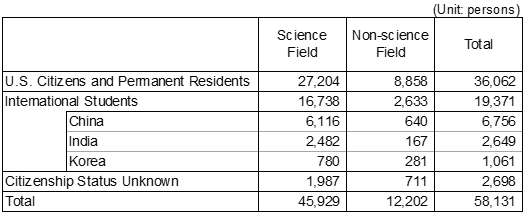

1. Decline of U.S. Science and Technology Competitiveness

In 2024, among the 45,929 doctoral degree recipients in the United States in the field of science (including social sciences), 6,116 were Chinese international students, accounting for 13.3% of the total and 36.5% of all international students (16,738) (Figure 3). When including fields outside science, 6,756 Chinese international students received doctorate degrees (11.6% of the total, 34.9% of international students). Of these, 78.0% remained in the United States after graduation (Note 13). For the United States, Chinese international students represent a significant source of human capital.

2. International students are classified as “temporary visa holders.”

3. China’s data include Hong Kong.

Source: Compiled by the author based on National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, “Survey of Earned Doctorates 2024,” August 28, 2025

To begin with, the U.S. high-tech industry has long depended on the inflow of talented individuals from overseas. Iconic examples include Google co-founder Sergey Brin (born in Russia), Tesla and SpaceX founder Elon Musk (born in South Africa), and NVIDIA founder Jensen Huang (born in Taiwan), who transformed the semiconductor industry. Immigrant scientists and engineers, including these individuals, have not only founded companies, but have also created new industries through venture capital activity and investment in research and development, sustaining the competitive advantage of the U.S. economy. If this international inflow of talent stalls, there is a risk that the very status the United States has built over many years as the “center of global innovation” will be shaken.

In fact, the Federation of American Scientists delivered the following warning that brain drain poses a serious threat to the United States, leading to a decline in science and technology strength and a loss of national competitiveness (Note 14).

First, the “magnetism” that the United States has cultivated over many years that attracts outstanding scientists and researchers from around the world is weakening. As a result, international personnel educated at U.S. universities are returning to their home countries or migrating elsewhere, diminishing the United States’ ability to attract the most brilliant minds.

Second, due to insufficient research funding and uncertainties about career prospects, young scientists and engineers are losing the incentive to remain in the United States. If this trend continues, it carries the risk of losing an entire generation of young scientists who should be driving future innovation, potentially weakening the foundation of U.S. research.

Third, brain drain is not merely a loss of human capital; it leads to the loss of the intellectual capital that underpins innovation, industrial competitiveness, and national security. These risks could cause the United States to fall behind in international competition, particularly in the fields of AI and energy.

2. Understanding China’s Scientific and Technological Advancement through the Nature Index

Meanwhile, China is achieving a leap forward in science and technology by making the most of domestic and international resources. This can be confirmed in the Nature Index by Nature.

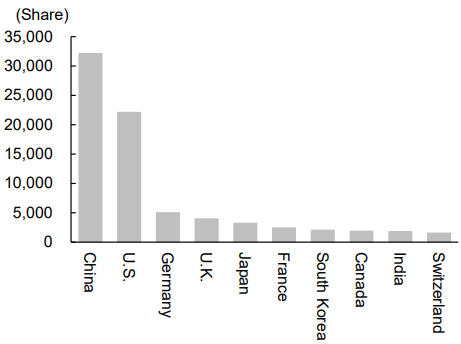

The Nature Index is a database and a ranking system that tracks and evaluates high-quality scientific research output by universities, research institutions, and countries worldwide. It focuses on research quality by considering only primary research articles published in top-tier academic journals selected by an expert committee. According to this index, China’s Nature Index value in the first survey covering papers published in 2013 was about one-third of that of the United States, but it surpassed the United States for the first time in 2022 to take first place, and it exceeded the United States by 45.5% in 2024 (Figure 4).

2. For coauthored papers, there are two counting methods: "Count," which adds one to each institution and country based on each author’s affiliation, and "Share," which allocates credit among authors so that each paper contributes at most 1.0. The latter method used here more accurately reflects contributions in collaborative research.

Source: Plackett, Benjamin, “Nature Index 2025 Research Leaders: United States Losing Ground as China’s Lead Expands Rapidly,” Nature, June 11, 2025.

In the Nature Index rankings of research institutions, as of 2024, Chinese institutions account for eight of the top 10. The Chinese Academy of Sciences (1st), the University of Science and Technology of China (3rd), Zhejiang University (4th), Peking University (5th), the University of Chinese Academy of Sciences (6th), and Tsinghua University (7th) dominate the upper ranks, and as for research institutions outside China, only Harvard University (2nd) in the United States and the Max Planck Society (9th) were included (Note 15). Looking at trends by subject, China ranks first globally in chemistry, physical sciences, and earth and environmental sciences. While the United States continues to demonstrate strength in biological sciences and health sciences, it is being outpaced by China’s growth in other fields.

VIII. The Accelerating Realignment of the Global Science and Technology Power Structure

The retreat of U.S. science and technology policy and the Chinese government’s aggressive investment in human resource and funding is significantly disrupting the traditional U.S.-centric international research order. Led by the return of Chinese researchers, inflows of other researchers into China are also expected to accelerate. In fact, an increasing number of researchers concerned about the research environment in the United States and Europe are moving to China in search of more stable funding and opportunities to participate in large-scale projects (see BOX2 for researchers moving to Chinese universities from overseas, excluding returnees). China will grow in importance not only as a “destination for studying abroad” but also as a “research hub.”

Furthermore, by combining the international networks brought in by returning researchers with China’s abundant domestic funding and infrastructure, China is no longer merely a research cluster but has begun to function as a global hub of academic exchange. The venues for international conferences and the centers of large-scale collaborative research are shifting to China. Its influence is growing in setting priorities for research topics as well as in establishing international standards and guidelines for scientific research and technological development.

These changes are intensifying the U.S.-China competition for technological supremacy while offering opportunities for expanding resources and research hubs within the global research environment. Going forward, how countries engage with the new research networks centered on China will become a critical issue.

BOX 1: Returning Scientists Who Played the Leading Roles in the “Two Bombs and One Satellite” Project

In China during the Mao Zedong era, which was effectively closed off from the outside world, the promotion of the “Two Bombs and One Satellite” project―the development of the atomic bomb, the hydrogen bomb, and an artificial satellite―marked a decisive turning point for national security and the advancement of science and technology. At its center was the contribution of scientists who had returned from overseas.

Many of the 23 recipients of the “Two Bombs and One Satellite Merit Award” in 1999 had studied or conducted research overseas, and each played a significant role in fields such as missile design, space technology, and nuclear weapons development.

Qian Xuesen (1911-2009) studied at the California Institute of Technology under Theodore von Kármá―hailed as the “father of aeronautics”― and took part in founding the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), then returned to China to oversee ballistic missile development, rapidly transforming China into a nation possessing operational ballistic missiles.

Ren Xinmin (1915-2017) studied aeronautical engineering at the University Clermont in France, and after returning to China led the design of satellite launch rockets, successfully launching China’s first artificial satellite, Dongfanghong-1, in 1970.

Deng Jiaxian (1924-1986) earned a Ph.D. in physics from Indiana University. After returning to China, he led the theoretical design of the atomic bomb (1964) and the hydrogen bomb (1967), elevating China to the world’s fifth nuclear-armed state.

Admiration for these pioneers has also become one factor encouraging modern scientists to return to China.

BOX 2: Researchers Other than Returnees Who Transferred from Overseas to Chinese Universities

The trend of overseas researchers other than returnees transferring to Chinese universities has become increasingly prominent in recent years, with three representative examples being Gérard Mourou, Kenji Fukaya, and Charles M. Lieber.

Gérard Mourou, a physicist from France, was appointed as a Chair Professor in the School of Physics at Peking University in October 2024. Having served as a professor at the University of Michigan in the United States and at École Polytechnique in France, he was awarded the 2018 Nobel Prize in Physics for his research on generating high-intensity ultrashort optical pulses.

Kenji Fukaya, a mathematician from Japan, moved from Stony Brook University in the United States to Tsinghua University in September 2024. He specializes in symplectic geometry, and has received numerous awards, including the Shaw Prize in Mathematical Sciences in 2025, the Asahi Prize, and the Mathematical Society of Japan Geometry Prize.

Charles M. Lieber, a former Harvard University professor specializing in nanoscience and chemistry and a recipient of honors including the Wolf Prize in Chemistry, was appointed as a Chair Professor at the Tsinghua Shenzhen International Graduate School in April 2025. He was arrested in 2020 under the China Initiative and was found guilty in 2021 on charges including fraud and tax offenses for allegedly failing to disclose to the U.S. federal government his participation in China’s Thousand Talents Plan and his contract with Wuhan University of Technology. The case sparked debate in the academic community and became a symbolic example of tightening regulations on academic exchanges with China.

First published in Japanese on October 20, 2025. English version updated on December 19, 2025.