I. Introduction

The term “involution”内巻[nèi juǎn]) originally referred to social problems in China related to excessive competition (Note 1). Especially among the younger generations, it was at first used to symbolize a sense of stagnation in school entrance examinations, employment, and daily life, and has widened as a concept expressing disappointment with situations in which efforts do not always lead to desired results (Note 2).

In recent years, the scope of this concept’s application has rapidly expanded into the economic arena. In particular, low-price competition among firms and excessive competition among local governments to attract industries are regarded as examples of “involutional competition.” These phenomena are not merely temporary intensifications of competition but reflect distortions in markets and institutions and have come to be regarded as important policy issues for the government.

This column first summarizes the actual situation, adverse effects, background and causes of “involutional competition,” and then presents the specific measures that are required in light of the Chinese government’s “anti-involution policy” initiatives which gained full momentum in 2024.

II. “Involutional Competition” in the Economic Field

In principle, economic competition serves the functions of improving efficiency and promoting innovation. However, in China, inefficient competition that relies on excessive inputs of resources (capital, human resources, time)―so-called “involutional competition”―has become a problem. Particularly serious is the fact that such competition often yields meager benefits for all participants and may even result in negative outcomes in which everyone incurs losses. Excessive investment aimed at maintaining market share or status, a glut of undifferentiated products, and extreme price cuts are together hindering the healthy development of industries.

At the corporate level, “involutional competition” can be categorized into two main patterns. The first is “low-price competition,” in which companies ignore profitability and sell below cost. The second is “homogenization competition,” in which companies follow the actions of their competitors and repeatedly make capital investments and expand production without a strategy, leading to a flood of similar products and oversupply. Advertising wars waged to expand market share are also frequent. As a result, even if sales increase temporarily, the lack of improvements in quality or services prevents companies from earning long-term trust from consumers.

The problem of “involutional competition” reach beyond companies into the economic policies of local governments. The following phenomena are particularly notable:

(1) Overuse of preferential policies

In the name of attracting businesses and promoting regional development, local authorities often provide excessive benefits in areas like taxation, subsidies, and land supply, encouraging zero-sum competition with other regions.

(2) Unplanned industrial entry

By ignoring regional characteristics and long-term perspectives and rushing into emerging industries, overlapping investments and oversupply in the same sectors occur frequently.

(3) Market enclosure and exclusionary measures

By prioritizing the protection of local companies, restrictions on the entry of companies from other regions and the imposition of unfavorable conditions exacerbate market fragmentation and unfair competition.

III. The Adverse Effects of “Involutional Competition”

As “involutional competition” intensifies, its impact spreads beyond companies and industries to the overall economy and structure of society.

1. Micro-level impacts: Squeezing profits and stifling innovation

The intensification of “involutional competition” squeezes corporate profits and seriously affects business sustainability. Driven to cutting prices and reducing costs, companies see their profit margins shrink and are forced to postpone research and development as well as human resource development. This hinders innovation and industrial upgrades.

2. Industry-level impacts: Distorted market competition

“Involutional competition” is causing serious distortions in industrial structures. In mature industries, oligopolization is advancing, with incumbent industry leaders strengthening their market dominance, while entry opportunities for small and medium enterprises are narrowing. In emerging sectors such as electric vehicles, subsidies and policy support have led to a proliferation of companies that prioritize short-term competitive gains resulting from policy benefits over technological innovation and actual quality improvements. Such distorted market competition hinders efficient resource allocation and makes sustainable growth and structural transformation for entire industries more difficult.

3. Macroeconomic impacts: Deflationary pressure, excess supply, and insufficient domestic demand

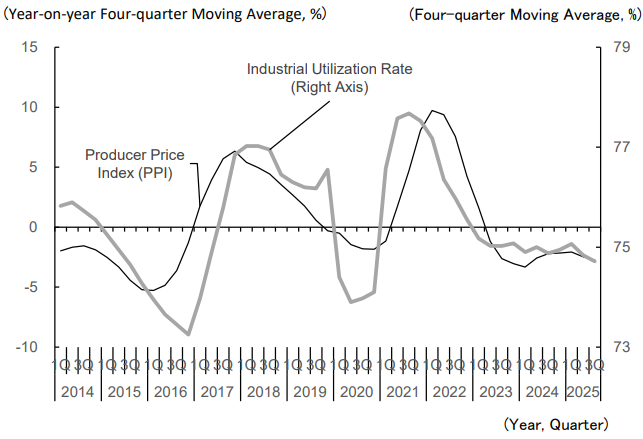

At the macroeconomic level, “involutional competition” expands production capacity and actual supply of products, while simultaneously exacerbating the decline in industrial utilization rates and increasing deflationary pressures (Figure 1). In fact, China’s Producer Price Index (PPI) recorded −3.6% (year-on-year) in July 2025, marking 34 consecutive months of negative growth. Price declines without productivity improvements deteriorate corporate earnings and act as a restraining factor on employment and wages. This could lead to sluggish private consumption and, ultimately, weaker domestic demand.

Source: Compiled by the author based on data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China

4. Impact on foreign relations: Export expansion and intensifying trade frictions

The export of massive volumes of inexpensive Chinese products generated by “involutional competition” has resulted in global oversupply in certain industries. This has prompted numerous anti‑dumping investigations and the imposition of high import tariffs on such Chinese products as steel, electric vehicles, and solar panels by the United States, the EU, Japan, India, and other countries. These external pressures directly affect the profitability of China’s exporting firms and exacerbate trade frictions, while at the same time highlighting the need for measures such as diversifying export destinations and shifting to local production.

5. Serious impact on fairness: Growing disparities

“Involutional competition” is also having a serious impact on economic fairness. First, intense competition in education and employment has created a structure in which “hard work does not pay off.” Especially disadvantaged groups such as people from rural areas, employees of small and medium enterprises, and non-regular workers are often forced into low wages and long working hours. As a result, social mobility has declined, and social stratification has become more entrenched. Furthermore, the uneven distribution of resources and oligopolization within industries are widening income disparities between sectors.

Ⅳ. Background and Causes of “Involutional Competition”

The“involutional competition”observed in China is not a temporary or accidental phenomenon, but the result of multiple structural factors acting in a layered manner.

First, chronic demand shortages underlie this phenomenon. While China, as the world’s largest manufacturing nation, possesses enormous supply capacity, growth in household consumption and private investment has been sluggish, highlighting the fragility of domestic demand. As a result, companies are forced into excessive competition to secure market share.

Second, deficiencies in the institutional framework and administrative mechanisms needed for healthy market competition are also a major problem. Some regional governments overly prioritize short-term performance evaluations and tend to implement excessive preferential and protective policies for enterprises within their jurisdictions. This reduces the efficiency of resource allocation, undermining a fair, unified market environment. Moreover, the underdevelopment of bankruptcy and corporate restructuring systems delays the market exit of inefficient firms, which preserves excess production capacity.

Third, strategic nurturing policies by the government have encouraged simultaneous entry into emerging industries, triggering “involutional competition.” For example, in the solar panel industry, subsidy competition among regional governments led to the disorderly expansion of production capacity and severe oversupply. Similarly, in the field of electric vehicles, numerous companies have emerged, intensifying price competition.

Fourth, the existence of so-called “soft budget constraints,” whereby even underperforming firms can expect fiscal support or bailouts from the government, is fueling overheated investment (Note 3). In China, not only state-owned enterprises but also private companies routinely receive support through government-affiliated funds and regional subsidies, significantly distorting the risk preferences and resource allocation of firms.

Lastly, Chinese corporate behavior remains deeply influenced by past successes and a tendency to prioritize short-term results. Since the reform and opening-up period, there is a history of companies expanding their market shares through low-price strategies. Therefore, even in today’s new market environment that demands high quality and diversification, they are entrenched in low-price competition, relegating brand building and research and development to a lower priority.

V. “Anti-involution” Added to the Policy Agenda

As “involutional competition” has intensified and its adverse effects have become more pronounced, responding to it has emerged as an important policy issue.

The Communist Party of China (CPC) leadership first mentioned the need to curb “involutional competition” in the context of economic policy at the Politburo Meeting of the Central Committee of the CPC held on July 30, 2024. However, looking back, the regulatory tightening on platform companies and cram schools that has been advancing since around 2020 can also be positioned as part of the corrective measures against this “involutional competition.” In fact, regulations on platform companies aim to curb the disorderly expansion of capital and promote anti-monopoly measures, while regulations on cram schools seek to address social problems such as excessive study burdens and soaring education costs.

On April 10, 2022, the Central Committee of the CPC and the State Council of the People's Republic of China issued the “Opinions on Accelerating the Construction of the National Unified Market,” setting out the basic principles of a national strategy aimed at correcting regional protectionism and market fragmentation and establishing a fair competitive environment (Note 4). Based on this, institutional development has progressed, and on June 13, 2024, the State Council promulgated the “Regulations for Fair Competition Reviews” which came into effect on August 1 of the same year. The regulations require the authorities to conduct a prior review of the impact on fair competition when formulating policies, with the aim of eliminating improper administrative interference.

Furthermore, at the Central Economic Work Conference in December 2024, the need “to comprehensively correct involutional competition” was emphasized. Subsequently, the Government Work Report delivered by Premier Li Qiang at the National People’s Congress in March 2025 continued to highlight the need to correct “involutional competition.” as a priority. In this way, China is aiming to achieve sustainable economic development by gradually advancing legislation and guidelines while fostering a fair competitive environment and market unification.

VI. Comparison between the “Anti-involution Policy” and the “Supply-side Structural Reform”

The currently advancing “anti-involution policy,” in a similar fashion to the “supply-side structural reform” implemented about a decade ago, is an effort to address structural issues in the Chinese economy. The “supply-side structural reform” was proposed by General Secretary Xi Jinping in November 2015 and has been fully implemented since 2016. Centered on the principle of “three cuts, one reduction, and one strengthening” (three cuts: eliminating excess production capacity, real estate inventory, and debt/leverage; one reduction: reducing corporate costs; one strengthening: strengthening weak areas), this reform focused particularly on eliminating excess production capacity in the steel and coal industries. The government used administrative measures to promote the closure and consolidation of inefficient factories.

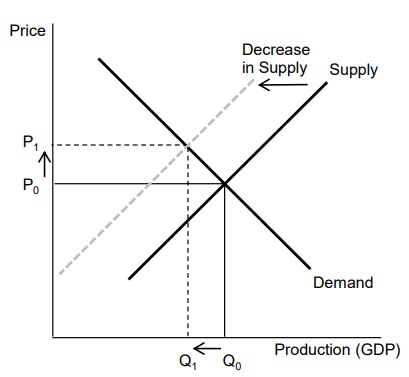

The “anti-involution policy” and the “supply-side structural reform” share the following concrete similarities. First, both policies were introduced under conditions where excessive supply and competition were forming economic inefficiencies, leading to deflation. In addition, both aim to shift from a growth model dependent on “quantity” to one that emphasizes “quality” and sustainable growth, with the goal of correcting inefficiencies inherent in the economic structure. Furthermore, because both emphasize the suppression of supply, they produce similar short-term effects, such as reduced production and rising prices (Figure 2).

On the other hand, there are also the following differences between the two policies.

First, in terms of the scope of policy targets, while the “supply-side structural reform” mainly focused on manufacturing industries centered on state-owned enterprises, such as steel and coal, the “anti-involution policy” spans a wide range of sectors―including electric vehicles, IT, education, employment, and overall public livelihoods―also encompassing private sector entities and the broader social system.

Next, in terms of policy instruments, while “supply-side structural reform” focused mainly on direct measures such as factory consolidation and workforce reductions, the “anti-involution policy” centers on more indirect and institutional approaches, such as legal and regulatory frameworks.

Finally, in terms of historical context, the “supply-side structural reform” was implemented around 2015, when economic growth was gradually slowing but policy space remained, whereas the “anti-involution policy” is being promoted amid a multifaceted downturn involving U.S.-China trade friction, the housing bubble collapse, and high youth unemployment.

Although both policies are aligned in pursuing economic sustainability, the “supply-side structural reform” was a short-term, intensive reform addressing inefficiencies in physical capital, whereas the “anti-involution policy” is a long-term and comprehensive attempt at institutional transformation that tackles issues in human resources and social systems.

VII. Measures Required to Overcome “Involutional Competition”

To overcome “involutional competition,” comprehensive measures aligned with the government’s policy direction are necessary.

First, a dynamic equilibrium between supply and demand must be achieved. To this end, it is necessary to expand domestic demand with a focus on consumption while promoting higher quality and differentiation on the supply side. In addition, expanding external demand by developing overseas markets while avoiding trade friction will help to mitigate excessive competition in the domestic market.

Second, restoring market order by strengthening the legal framework and supervisory systems is a necessity. Simultaneously improving market exit mechanisms to enable the smooth exit of inefficient firms will be beneficial in enhancing industrial efficiency.

Third, regional governments must refrain from protectionism and excessive preferential policies. In particular, in emerging industries, unplanned duplicate investments should be avoided.

Fourth, it is necessary for companies and industry associations to independently and autonomously adopt sound competitive practices to overcome “involutional competition.” Industry associations should urgently foster a culture of fair and honest competition by establishing industry guidelines and standards. Companies must also abandon their excessive focus on short-term, price-dependent strategies and shift their goals toward establishing long-term competitive advantages through technological innovation, brand building, and enhanced services.

Fundamentally, “involutional competition” is a structural problem accompanied by resource waste, institutional distortions, and individual exhaustion, posing risks not only to economic efficiency but also to sustainable development. To correct it, endeavoring beyond mere economic policy and fundamentally rethinking the nature of competition and institutional frameworks will be essential.

First published in Japanese on August 27, 2025. English version updated on October 31, 2025.