China has been undertaking massive foreign exchange intervention in a bid to stem a strengthening of the yuan, even after shifting to the managed floating system with the currency reforms carried out in July 2005. As base money increases with this action alongside foreign currency reserves, China is finding it increasingly difficult to control the money supply. To curb the rapid increase in liquidity, the monetary authorities originally placed an emphasis on suppressing the growth in base money through the issue of central bank bills, but subsequently switched to hiking the statutory reserve ratio, so as to reduce the burden of interest payments. In particular, with inflation accelerating from 2010 onward, the authorities have been raising the statutory reserve ratio to a record-high level as part of their credit tightening. This has led to a sharp slowing in money supply growth from the high levels recorded in 2009 when monetary easing was in full swing. This is expected to reduce inflationary pressure going forward.

A major shift in the prime means of sterilization

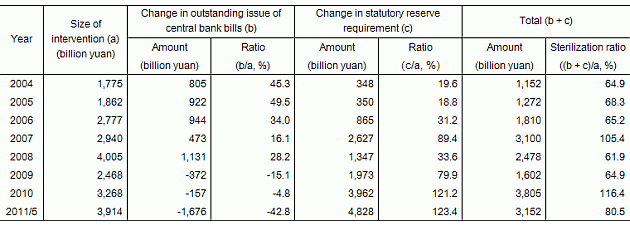

In an attempt to slow down the pace of the yuan's appreciation, China has been intervening in the foreign exchange market by selling yuan and buying dollars on a daily basis. If the base money injected into the market by the intervention is left as is, it can create an asset bubble and inflation through the expansion of liquidity. To prevent this from occurring, the authorities have been trying to sterilize its intervention through open market operations in which the central bank primarily issues its own bills and manipulates the statutory reserve ratio applied to commercial banks. In recent years, the scale of sterilization has been increasing in step with the expanding scale of foreign exchange intervention, and the prime means has been changing from open market operations to reserve requirement manipulation (Table 1).

Table 1: Open Market Operations and Reserve Requirement Manipulation as Means of Sterilization |

|

(Notes)

|

| (Source) People's Bank of China |

The scale of foreign exchange intervention refers to the increase in the "Position for Forex Purchase" in the "Summary of Sources and Uses of Credit Funds of Financial Institutions" published by the People's Bank of China. According to the data, the scale of the intervention reached 1,774.6 billion yuan in 2004, with 45.3% of this amount being sterilized through the issue of central bank bills (a net increase in the outstanding balance) and 19.6% through the hike in statutory reserve requirement. The ratio of sterilization combining both reached 64.9% of the intervention.

Even after China shifted to the managed floating system in 2005, the size of the intervention has continued to increase, reaching 2,939.7 billion yuan in 2007. However, in the same year the net increase in the issuing of central bank bills fell to an amount equivalent to only 16.1% of the size of the intervention. In contrast, the scale of sterilization through the hike in statutory reserve requirement exceeded that through the issuing of central bank bills, as the statutory reserve ratio was raised from 9.0% at the beginning of the year to 14.5% at the end of the year.

That situation has continued. Particularly since 2009, the scale of newly issued central bank bills has been falling below redemptions due to maturity, and the net increase in the outstanding issuing of central bank bills has turned negative. On the other hand, since the stance of monetary policy has shifted to tightening from easing in January 2010, the statutory reserve ratio has been raised 12 times, by 6 percentage points, in total reaching a record level of 21.5% as of July 2011. Base money frozen by this action has exceeded the scale of the intervention.

By switching its policy tool from the issuing of central bank bills to the hiking of the reserve ratio as just described, the central bank is able to contain the costs associated with the sterilization. The reason for this is that although the central bank does have to pay interest rates for both the bills it issues and the reserves deposited by commercial banks, the interest rates the central bank will pay for the latter (1.62% in the case of statutory reserve requirement and 0.72% in the case of excess reserves as of July 2011) are lower than those paid for the former (3.4% in the case of one-year bills). However, the hike of statutory reserve ratio may squeeze the profits of commercial banks.

Decelerating growth in money supply due to a lower credit multiplier

What kind of impact does a switching of the prime instrument of monetary policy from open market operation to reserve requirement manipulation have on money supply (M2), the intermediate target of monetary policy?

Conceptually, growth in M2 can be divided into two parts: growth in the base money and changes in the credit multiplier. In other words, the credit multiplier can be defined as M2 divided by base money, and if we rewrite as:

M2 = Credit multiplier x Base money,

we will see that growth in M2 is proportionate to growth in base money and changes in the credit multiplier. While the issuing of central bank bills directly suppresses the amount of base money, raising the statutory reserve ratio does not have a direct impact on base money but lowers the credit multiplier. (note)

In China, growth in base money is accelerating with the contraction in the scale of sterilization through the issuing of central bank bills, while foreign currency reserves continue to increase. However, growth in M2 (year on year) has slowed significantly from its peak of 29.7% in November 2009, to 15.9% in June 2011. The reason why growth in M2 is decelerating amid a sharp increase in base money is that the repeated hikes in the statutory reserve ratio have caused a fall in the credit multiplier through a rise in the reserve ratio that also covers excess reserves (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

Figure 1: Factor Analysis of Growth in M2 Contribution of the base money and the credit multiplier |

|

| (Note) Rate of change in M2 = Rate of change in base money + Rate of change in credit multiplier. The rate of change in each variable is measured in terms of the first difference of its natural logarithm. |

| (Source) People's Bank of China and the CEIC Database |

Figure 2: Credit Multiplier Inversely Proportional to Reserve Ratio |

|

| (Note) The statutory reserve ratio varies based on the size of banks, and that applied to large banks is used here. Reflecting the fact that this is higher than the reserve ratio applied to small and medium-sized banks, the reserve ratio (including excess reserves) of the banking sector as a whole may be lower than the statutory reserve ratio (for large banks). |

| (Source) People's Bank of China and the CEIC Database |

Cooling inflation

As suggested by the economics dictum "inflation is always a monetary phenomenon," money supply is the critical variable influencing the inflation rate in China, as in other countries. Although inflation reached 6.4% in June 2011, the highest level for three years, this is simply the aftereffect of the ultra-easy monetary policy adopted following the collapse of Lehman Brothers. While there is a concern that inflation may continue to rise, that possibility appears low, given that growth in the money supply is slowing as the tight monetary policy proves effective.