Economic, environmental and food security are central to Japan’s G7 agenda as prime minister Kishida hosts the leaders from the group of advanced economies in Hiroshima in May. The agenda aims to be relevant for the ‘Global South’ as global inflation, uneven recovery from the pandemic and the food and energy crises, a fallout from Russia's invasion of Ukraine, are challenges that are not unique to advanced economies.

Great power strategic competition between China and the United States and the rise of an assertive China has elevated the issue of economic coercion on Japan’s G7 agenda. China has tried to use its economic power to extract political concessions from Japan and other countries, including South Korea, the Philippines and most recently Australia.

The response to these new circumstances in Japan has seen the introduction of economic security laws that aim to protect Japanese intellectual property and critical infrastructure and make supply chains more resilient. Much of this is sound economic policy but there is also an element of protection from Chinese practices and an attempt to avoid collateral damage from US-China strategic competition. Both Beijing and Washington are forcing countries to choose sides in a competition where each sees the gain of the other as a loss to them.

Australia and India have been invited to the G7 summit as guests. Both are members of the strategic Quad grouping with Japan and the United States, and India is chairing the G20 this year and an important leader of the ‘Global South’. Australia has much to share from its experience in withstanding Chinese economic coercion since 2020.

Learning the right lessons from Australia’s experience is important to helping Japan secure a safer and more prosperous regional and global economy.

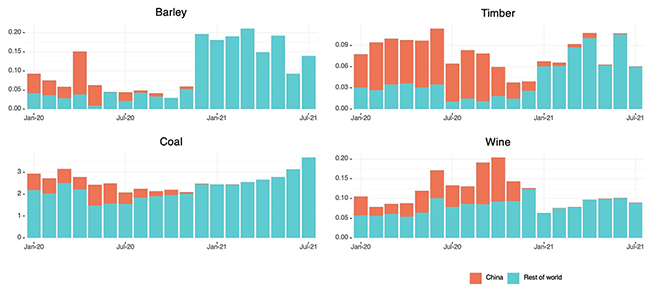

From May 2020 Beijing blocked the import of a dozen or so Australian goods worth around A$20 billion annually including coal, wine, barley and lobsters where China was the major market. The context was a deteriorating political relationship between Canberra and Beijing and a trade deal between Beijing and Washington that required increased Chinese imports of US agricultural and other goods. American wine exports, for example, quickly took Australia’s market share in China even as Washington intoned support for Canberra.

Such large disruptions to trade — as Japan experienced in 2010 with rare earth metals from China — are costly and threaten economic security. But retreat from openness and economic engagement is not the answer. That’s a pathway to a poorer and less secure world.

Australia’s exports to China remained steady in 2020 and grew by 14 per cent in 2021 and again by 6 per cent in 2022, all while both countries and the global economy went in and out of COVID lockdowns and downturns. Australian exports of iron ore, which could not be easily sourced by China from elsewhere, and the rapid growth of other commodities like lithium exports, led the way. China accounted for over 40 per cent of Australian goods exports during that time and helped Australia weather the economic effects of the pandemic.

Australia is no stranger to having one country dominate its international trade shares, in the past having had Japan, the United States and the United Kingdom account for around as much as China does today. That is a sign of success in utilising Australian economic endowments and taking advantage of opportunities internationally. Australia has put in place institutions and economic policy settings to manage these highly interdependent economic relationships and managed the inevitable shocks in their fortunes, some self-inflicted, that occur from time to time.

Chinese trade sanctions caused Australian exporters, especially wine and lobster exporters, huge losses. But most exporters quickly found other markets as Chinese imports of barley, coal and other commodities did not slow and opened up other demand. Flexible markets in Australia helped but the crucial external source of resilience was an open multilateral trading system.

[Click to enlarge]

Australian exporters found other markets because they were open thanks to the multilateral trading system. Neither exporters nor the Australian government knew exactly where those markets would be ahead of time. The redirection of trade was led by market opportunities. At the centre of that system is the WTO, that despite all its weaknesses, holds together the scaffolding of the trading system with a patchwork of WTO-plus free trade agreements built around it.

Europe, Australia, Singapore and two dozen other WTO members, including and importantly China, have signed onto the Multi-Party Interim Appeal Arbitration Arrangement (MPIA) so that WTO rules are enforceable even while the United States holds the system hostage with its veto of arbitration judges. Japan has now joined the MPIA, a major development that signals Japanese commitment to take a lead on international economic rules. Australia has cases against China in the WTO that will be enforceable. As the world’s largest trader, China has a huge stake in the existing multilateral trading system, having a track record at least as good as Europe and the United States in abiding by major rulings like its loss to Japan in the rare earth metals dispute a decade ago.

China’s non-observance of the spirit of multilateral trade rules and gaming the system are not reasons to give up on the WTO. Chinese efforts at economic coercion have almost entirely failed and in every case its actions backfired economically or politically. Multilateralism diffuses power and keeps options open especially for smaller countries.

It is possible to find ways to mitigate and diffuse trade risks by deepening engagement and by strengthening and extending the rules, rather than by avoiding engagement. Economic engagement builds national wealth and power and when combined with multilateral rules, broadens the range of strategic policy options available to national policy makers.

A Chinese economy and society that is much less integrated into the global economy is one with far fewer constraints and much more of a security risk.

Russia’s strategic use of gas supplies against Europe is sometimes cited as a counterpoint to the argument for interdependence. But Russia was not integrated into European supply chains; European energy dependence on Russia is qualitatively different from the complex interdependence in East Asia, and interdependence underpinned by multilateralism effectively diffuses risks.

Nowhere is the power of multilateralism understood better, and exercised more instinctively, than in Southeast Asia’s ten member ASEAN grouping. There’s an opportunity for Japan to reinforce that and to keep the Indo-Pacific free and open in the 50th anniversary Japan–ASEAN summit later this year and through working with ASEAN to build economic security through intensifying economic cooperation in RCEP, including with China.

Small and medium-sized powers are protected by international rules and markets. Open, contestable markets importantly constrain big powers who will fully choose to skirt established rules and use economic leverage, with no thought for the ramifications. That is the primary lesson of Australia’s experience of economic coercion as the economic weapons that China fired at Australia were blunted by the multilateral trading system. Even if big powers deviate from the rules, defending and extending the multilateral system is still the top priority for the rest of the world — not following them down that self-destructive road.

The strategic interest on China is still to lock it into rules, norms and markets. Australia and Japan should take China’s application to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership, or TPP-11, to serious negotiation, defining the milestones in Chinese reform that are needed for it to attain membership. CPTPP membership can be expanded without eroding the rules or standards.

The reality now is that the United States has vacated leadership of the global trade regime and become a source of uncertainty as it deals with its own domestic challenges. The United States Trade Representative Katherine Tai disparaging the unfavourable WTO ruling over its use of steel and aluminium tariffs in the name of national security in December makes advocacy of a rules-based international order that much harder.

But the rest of the world needs the rules-based international order for economic security. Japan’s leadership was crucial to the conclusion of CPTPP. The global economic situation has deteriorated since then and the challenge has become much harder. Australia and Japan are actively shaping the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework to keep the United States locked into Asia, and our joint objective should still be to get the United States back into the CPTPP. These efforts should not come at the expense of the main game of elevating collective political commitment to preserving and strengthening the multilateral trading system, especially the WTO.