Tariff escalation between China and the US will result in decoupling of goods trade, raising fears that Chinese exports destined to the US market in 2024 will be redirected or deflected to third markets. Fearful of intensified competition from Chinese products, some business associations and officials are calling for pre-emptive measures by importing governments. This column uses the most disaggregated US import data available to demonstrate that there are only 101 Chinese product categories where these were sufficient exports in 2024 to realistically raise export redirection risks. The majority of those Chinese products were losing ground in the US market, calling into question whether, in fact, the exporters responsible will become fearsome competitors in world markets, as some assert.

Now that exports from China face astronomical import tax (tariff) rates in the US market, concerns have been raised that these goods will be redirected – or ‘deflected’, to use the trade policy term – to third markets.

Some worry this will intensify competition for customers, result in price cutting and profit margin reduction wherever this ‘wave’ of Chinese exports ends up. Over the past fortnight stories amplifying these concerns were published in the New York Times and the Financial Times.

Certain business associations have already started lobbying governments to raise import barriers – arguing that it is better to take pre-emptive action than to deal the fallout from Chinese dumping. Such proposals risk setting off a domino effect of import restrictions on Chinese exports, likely triggering Chinese retaliation.

If corporate executives and government officials misjudge the extent and consequences of Chinese export redirection, then what started off as a bout of American trade unilateralism followed by Chinese retaliation could degenerate into system-wide increases in trade restrictions. The likelihood of a repeat of the 1930s resort to protectionism would rise. There is much at stake.

The purpose of this column is to gauge the competitive threat in third markets from Chinese trade deflection in the months and years ahead. In a first step, I identify the products where a key precondition for Chinese trade deflection is met.

The second step is to marshal evidence on whether Chinese exporters of these products have been gaining ground in the US market to assess whether they are likely to be formidable rivals in third markets. Just because a product can be deflected in large quantities from the US market doesn’t mean the Chinese firms responsible have been gaining in competitive strength.

This column complements the one written by Fernando Martin and myself (Evenett and Martin 2025). Rather than the prospective analysis presented here, in that column we looked back at the onset of the first US-China trade war to assess the extent of Chinese trade deflection and the frequency with which importing governments took defensive measures in response. We found that, within 18 months of the onset, trade deflection was detected in 42% of possible cases.

Moreover, we found that importing governments – taken here to be the rest of the G20 and Switzerland – took defensive measures in only half of the instances of trade deflection. For sure, there was significant variation across importers in their exposure to Chinese trade deflection and in their resort to defensive measures.

From this, we concluded that, yes, there is precedent for Chinese trade deflection, but not on the scale that some contend (now or then). Furthermore, it seems many importing governments allowed their consumers and companies to benefit from greater supplies of Chinese products at lower prices. These governments’ behaviour calls into question the assumption that all Chinese trade deflection must be bad and therefore merits defensive measures.

Now that China faces even higher import tariffs than in 2018 and 2019, it makes sense to use the latest available US import data to assess the competitive threat posed by Chinese products that may in the near term be redirected from the US market to third markets.

China’s exports to the US are concentrated

The most granular classification of US imports groups them into 18,701 product categories (Note 1). It is a testament to how concentrated China’s exports to the US are that more than $500 million was shipped in only 101 product categories in 2024 (Note 2). Those 101 product categories accounted for $213 billion of the $429 billion imported into the US from China in 2024. An Excel file is available that identifies all of these 101 product categories.

Why focus on these 101 product categories? Surely, any ‘wave’ of Chinese exports redirected to third markets requires large amounts to be exported to the United States in the first place. Sixty of the 101 product categories are found in five ‘chapters’ of the US Harmonized Tariff Schedule.

Twenty-three were in Chapter 85 (lithium batteries and smartphones being the biggest ticket items), 10 were in Chapter 84 (computers and computer parts), and nine each were in Chapter 39 (plastics), Chapter 87 (motor vehicles and parts) and Chapter 95 (toys and video games). The upshot: many goods sectors are not at risk of deflection.

Next, I deploy more US import data to assess whether Chinese exporters of these 101 products are gaining in strength in the American market. My assessment is based on absolute and relative performance measures – it is, therefore, data-driven rather than speculative.

Absolute performance assessment

For each of these 101 goods exported from China, I examined their absolute performance in the US market from 2022 to 2024 (Note 3). I will be transparent about my priors: if Chinese exporters in these product categories were in retreat in the US market, then they are less likely to be fearsome rivals in third markets. The opposite could be true. The approach taken here is to let the data reveal the degree of absolute competitive strength of Chinese exporters in these product categories.

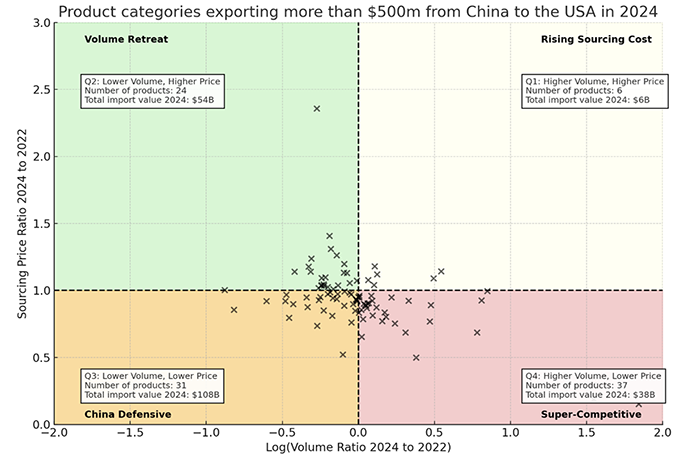

I checked if the average price paid per unit to the exporter in China (excluding transport costs and tariffs) fell – indicating reduced sourcing costs and greater potential to lower prices in the US market. I was also interested in whether the volume of a product exported to the US rose. This information was available for 98 of the 101 product categories. The two measures computed are plotted in Figure 1. Each product falls into one of four quadrants.

[Click to enlarge]

The upshot is that there is a huge variation across the 98 product categories in their recent (absolute) performance in the US market. Thirty-seven product categories saw the quantity shipped to the US (import volumes) rise from 2022 to 2024 as well as sourcing costs fall. These 37 product categories were associated with $38 billion of imports into the US in 2024 and I label this quadrant of Figure 1 “super-competitive.” Readers can check if local firms of interest compete against Chinese rivals in these 37 product categories (Note 4).

By far the largest value of imports was associated with products in the China Defensive quadrant. Here, Chinese exporters have shipped lower volumes even though their sourcing costs have fallen. A total of 31 product categories accounting for $108 billion of imports were in this quadrant.

Thirty other product categories are found in the two quadrants where Chinese sourcing costs have risen. The latter may reflect diminished cost control or upgrading of these Chinese products. In either case, the likelihood is that there is a floor on the prices of these products should they be deflected to third markets – undercutting price wars concerns.

On the basis of this evidence, generalising the competitive threat posed by Chinese exporters of deflected products is unwarranted. Granular, case-by-case assessments are warranted.

Relative performance assessment

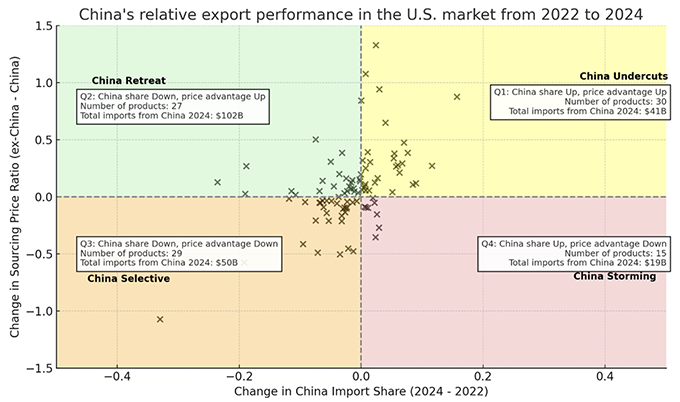

For many, corporate performance is best thought in relative terms—I have a lot of sympathy with that view. Consequently, I separated Chinese and non-Chinese suppliers of each product category and calculated the change in the Chinese import share in the US between 2022 and 2024 (Note 5).

I also calculated the difference between the proportional change from 2022 to 2024 in average sourcing price paid by non-Chinese suppliers and those of Chinese exporters. To fix ideas: my priors are that increasing Chinese import shares while coping with average sourcing costs that rise faster (Note 6) in China is associated with more fearsome Chinese exporters – these cases are the ones where competitors in third markets might want to worry about.

Data are available to make these calculations for 94 of the 101 product categories. The resulting metrics are plotted in Figure 2. Again, so diverse are the findings across the 101 products that I separate them into four quadrants.

[Click to enlarge]

Only 15 product categories involve higher Chinese import shares despite Chinese sourcing costs rising faster than rivals, the so-called China Storming quadrant in the lower right-hand side of Figure 2. Arguably, firms competing with Chinese rivals in this quadrant may have something to worry about if the same competitive strengths the Chinese firms have in the US market carries over to the third markets (Note 7). Some $19 billion of Chinese exports are in the China Storming quadrant, the smallest total of the four quadrants – a finding that cautions against exaggerating the system-wide threat represented by ultra-competitive Chinese firms deflecting products originally destined to the US market.

A striking finding in Figure 2 is that the Chinese import share is falling in 56 product categories (the China Retreat (Note 8) and China Selective (Note 9) quadrants). These products account for a majority of the plausible candidates for Chinese trade deflection and comprise three-quarters of the imports into the US of those products where more than $500 million of each were shipped by China in 2024.

This is not to imply that firms having Chinese rivals in these 56 product categories have ‘nothing to worry about’. Rather, it is that their rival’s diminished competitive position in the US market calls into question whether these firms would constitute a first-order threat in third markets. Moreover, it raises the question what steps other firms took to put these Chinese exporters on the back foot in the American market.

Combining assessments

I now turn to the question of whether the Chinese products that did well on the absolute performance criteria also excelled on the relative performance criteria. Surely it is these Chinese particular exporters that are likely to become fearsome competitors on third markets?

For the 94 product categories that could be classified into a quadrant in both the absolute and relative performance assessments, I then produced the summary Table 1 with 16 cells. In only two product categories – amounting to just over a billion dollars of US imports in 2024 – were Chinese exporters able to increase volume, increase import share, reduce their sourcing costs in absolute terms while their non-Chinese rivals were cutting their sourcing cost by proportionally more. These two product categories were footwear and plastic table coverings. These are not the product categories one typically hears business people and policymakers worry about when they discuss Chinese manufacturing prowess.

The middle columns and rows of this summary table reinforce a point made earlier – that the majority of products where China shipped more than $500 million in 2024 were ones where the volume of goods shipped and Chinese import shares were falling. Such poor performance undercuts assertions that, having lost access to the US market on account of higher tariffs, the Chinese exporters in question will be formidable competitors in third markets.

[Click to enlarge]

Concluding remarks

The tariffs imposed this month by the US on Chinese imports have reached unprecedented levels and will accelerate the decoupling of goods trade between these two economies. In the future, a settlement between Beijing and Washington may result in lower import tariffs, but there is no expectation that American import tariffs on Chinese products will return to levels seen during the Biden administration (Note 10). As a result, China’s exporters may seek out new markets in the months and years ahead, leading to fears that trade deflection will undermine the commercial performance of rival firms operating in third markets.

A central lesson from this briefing is that publicly and freely available high-quality data exists to enable analysts, executives, and officials to (a) identify at a highly granular level in which products Chinese trade deflection is likely to happen; and (b) assess whether the exporters responsible have been gaining a greater foothold in the US market, likely reflecting underlying competitive strengths. Fear should be set aside – discussions on the form and scale of future trade deflection can and should be informed by evidence.

Two broad findings arose from this analysis. The first is that Chinese exports to the US are highly concentrated in about 100 product categories which accounted for around half of total Chinese exports to the US in 2024. For trade deflection to occur there has to be significant amounts of Chinese exports in the first place – so looking at the product categories where more than $500 million was shipped from China in 2024 is a sensible starting point. Sixty of those product categories are associated with a limited number of business sectors (Note 11).

The second finding is that most of the products where there were sufficient Chinese exports to the US in 2024 to make trade deflection a distinct possibility were also ones where Chinese firms have been on the back foot in American markets. Now, there may well be some superstar Chinese firms shipping these goods in these lacklustre categories but, broadly-speaking, most of the candidates for trade deflection are products where Chinese export volumes and Chinese shares of total US imports have been falling since 2022. If unassisted by Chinese government export support, then one must question how much of a threat these Chinese exporters will become to rivals in third markets.

In principle, two factors could revise the sanguine assessment presented here. First, that the US restores the now-paused high import tariffs on other exporters. Taking this step would increase the range and value of goods ripe for export redirection. Second, that Beijing – or for that matter any government hit by significant US import tariff increases — offers significant incentives to affected exporters. Those incentives may overcome, in whole or in part, the competitive disadvantages that held back their ability to penetrate the US market. Tracking state-provided export support will be at a premium going forward.

This article first appeared on VoxEU on April 25, 2025. Reproduced with permission.