Increasing geopolitical fragmentation can create dilemmas for neutral countries. This column studies how firms in neutral countries adjusted their supply chains in response to Western sanctions on Russia. Firms in non-sanctioning countries reduced exports of sanctioned products to Russia when their headquarters were in sanctioning countries. However, domestic firms in neutral countries significantly increased exports of sanctioned products, undermining sanctions. Sanctioning multinational enterprises expanded exports to both sanctioning and Russia-friendly countries, blending compliance and evasion. To improve sanctions, stronger secondary sanctions and multinational enterprise involvement are essential.

In today’s geopolitical landscape that is often characterised as the ‘New Cold War’, many neutral countries face a dilemma: comply with or evade US-led sanctions against Russia. While neutral nations rely on globalisation, sanctions severely restrict trade, offering little incentive for compliance. Their non-participation undermines the effectiveness of Western sanctions.

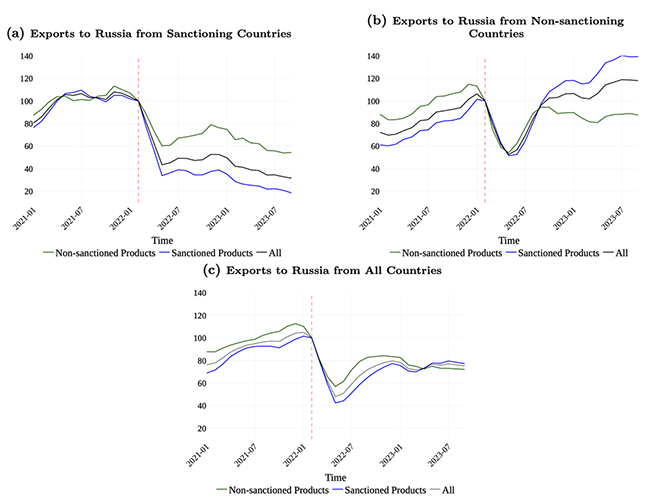

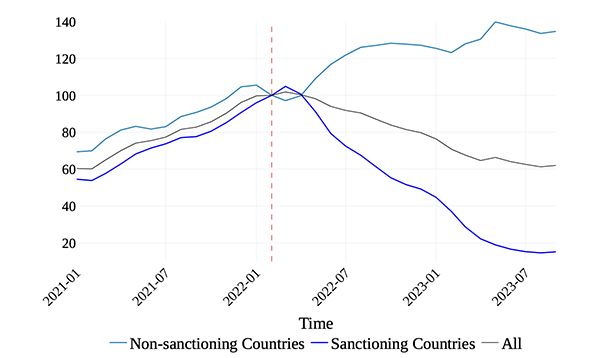

Figure 1 shows that sanctioning countries reduced exports of sanctioned products to Russia by 80%, while non-sanctioning countries increased their exports of these products by 40%. Despite sanctions, Russia’s total imports of sanctioned goods did not decrease relative to non-sanctioned products due to non-sanctioning countries. Figure 2 highlights that sanctioning countries cut imports from Russia by 80%, while non-sanctioning nations increased them by 40%.

As enhancing compliance by firms in non-sanctioning countries remains a political priority, in Li et al. (2024), we investigate how these firms adjusted their supply chains to Western sanctions on Russia. We focus on two key mechanisms: extraterritorial export sanctions and financial sanctions, through which Western sanctions on Russia affect supply chains in neutral countries. Multinational enterprises with headquarters in sanctioning countries (sanctioning MNEs) are required to comply with ‘long-arm’ sanctions, which restrict the export of sanctioned products using technology or inputs from sanctioning countries. While domestic firms and non-sanctioning MNEs are technically subject to these regulations if they rely on sanctioning countries for technology or inputs, their compliance is uncertain due to enforcement challenges.

[Click to enlarge]

Data source: UN Comtrade.

Data source: UN Comtrade.

How did extraterritorial sanctions on product exports affect sanctioning MNEs and domestic firms’ exports to Russia?

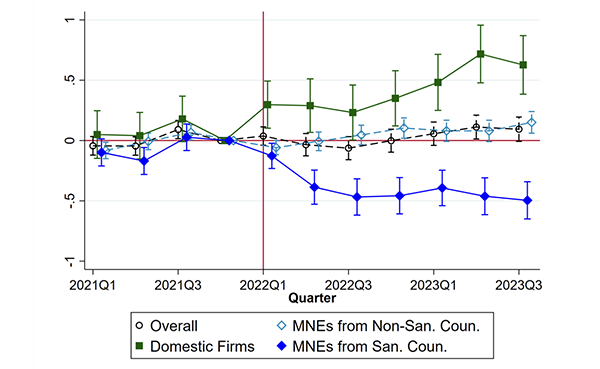

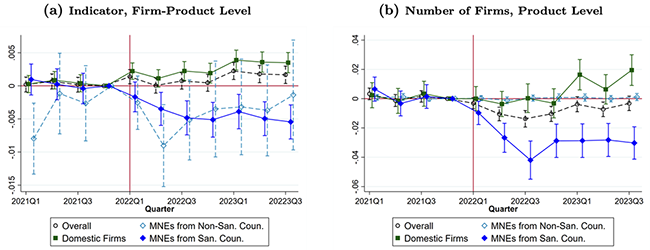

We first analyse how Western extraterritorial sanctions on product exports impacted MNEs and domestic firms in neutral countries. Applying a difference-in-differences model that interacts product sanction status with time, while controlling for granular fixed effects, our results show that MNEs headquartered in sanctioning countries reduced their exports of sanctioned products to Russia by 34% more than non-sanctioned products, demonstrating strong compliance with sanctions. However, domestic firms in neutral countries increased their exports of these sanctioned goods by 36%, and non-sanctioning MNEs saw a smaller increase of 6% (Figure 3).

Although MNEs from sanctioning countries complied, firms in neutral countries capitalised on the opportunity to expand their exports, thereby diminishing the overall effectiveness of the sanctions.

Which firm type played the largest role in sustaining Russia’s access to sanctioned goods?

We find that domestic firms were the main drivers of increased exports of sanctioned products to Russia from neutral countries. Enhancing compliance from these firms could significantly limit Russia’s access to these goods. Using a new decomposition formula, we find that domestic firms contributed 146% of the rise in sanctioned product exports from non-sanctioning countries to Russia, while sanctioning MNEs contributed -51% as they reduced sanctioned product exports.

If neutral country domestic firms and non-sanctioning MNEs could comply as much as sanctioning MNEs, Russia’s total imports of sanctioned products could decrease by 76%, and overall imports by 53%, as Russia is now heavily relying on non-sanctioning countries for these supplies.

The influence of consumer and import markets on compliance of neutral-country firms

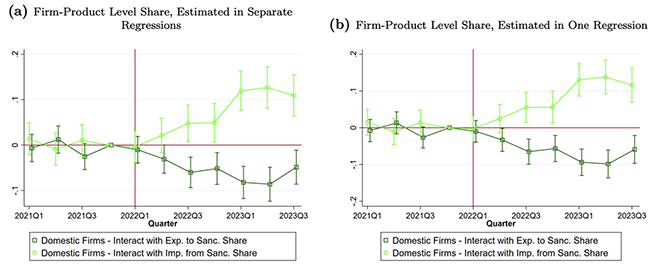

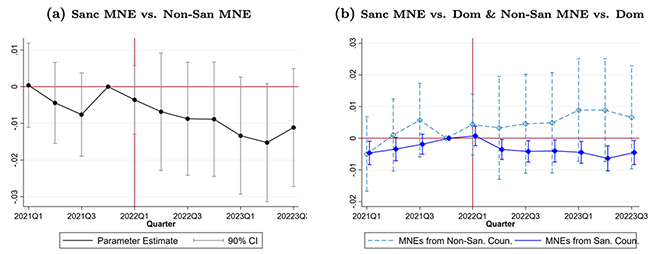

Consumer markets play an important role in shaping the compliance behaviour of domestic firms in neutral countries. Firms with a higher export share to sanctioning countries reduced their sanctioned product exports to Russia (Figure 4). These firms face a higher opportunity cost for violating sanctions due to the potential loss of access to important consumer markets in sanctioning countries. Moreover, penalties against them are easier to enforce given their presence in sanctioning countries.

On the other hand, firms that sourced more inputs from sanctioning countries increased their exports of sanctioned products to Russia. Despite being subject to extraterritorial export constraints, these firms likely prioritised profits over compliance, as the gains from exporting to Russia outweigh the perceived risks of penalties. With more imported inputs from sanctioning countries, they became even better equipped to export sanctioned products to Russia. Strengthening secondary sanctions should focus on monitoring firms importing from sanctioning countries that are also selling sanctioned products to Russia.

[Click to enlarge]

How did neutral country firms restructure their supply chains to bypass sanctions?

Domestic firms in neutral countries significantly increased both their imports from sanctioning countries and their exports of the same sanctioned products to Russia. Figure 5a demonstrates a notable increase in the likelihood of domestic firms importing from sanctioning countries and exporting to Russia for the same products. In contrast, the same pattern was not observed for MNEs from sanctioning or non-sanctioning countries, which instead reduced their participation in trade rerouting activities. Additionally, Figure 5b shows an increase in the number of domestic firms involved in trade rerouting, a decrease for sanctioning MNEs, and no significant change for non-sanctioning MNEs.

This pattern accounted for 69% of the total increase in sanctioned product exports to Russia from neutral countries.

[Click to enlarge]

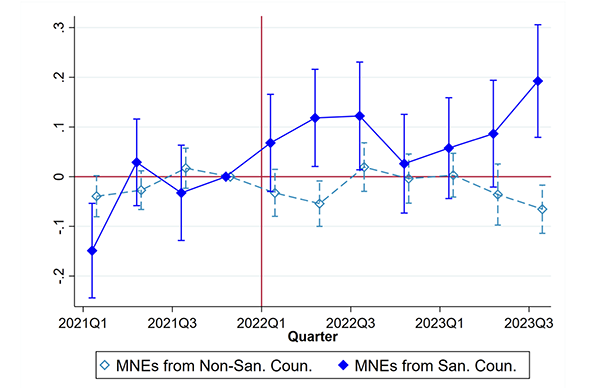

Sanctioning MNEs increased sanctioned product exports to both sanctioning countries and Russia-friendly countries

As sanctioning MNEs reduced their exports of sanctioned products to Russia, they simultaneously increased exports of these products to sanctioning countries as well as SPFS (Note 1) and CIS (Note 2) countries, which are considered friendly to Russia. The first adjustment suggests a genuine effort to find new customers, as products sold to sanctioning countries are unlikely to be redirected to Russia. However, Figure 6 shows that sanctioning MNEs also significantly increased exports of sanctioned products to Russia-friendly countries, including SPFS and CIS nations. This second adjustment hints at a possible attempt by sanctioning MNEs to circumvent the sanctions.

Sanctioning MNEs reduced imports from Russia more in financially risky sectors

Following the empirical strategy outlined by Manova et al. (2023), we find that sanctioning MNEs reduced imports more in financially risky sectors (Figure 7). Financial sanctions, such as banning numerous Russian banks from SWIFT, heightened risks in the Russian economy, particularly for sectors reliant on external financing and trade finance. Compared to domestic firms and non-sanctioning MNEs in developing countries, sanctioning MNEs are less likely to secure financing from their headquarters' banks for trade with Russia. This increases the costs of importing from Russia, resulting in further trade reductions in financially risky sectors.

[Click to enlarge]

Conclusion

Sanctioning countries have made significant progress in reducing trade with Russia, cutting sanctioned product exports by 80%, non-sanctioned product exports by 40%, and imports by 80%. However, neutral countries remain a key loophole, allowing Russia to access critical supplies. Our analysis shows that while MNEs from sanctioning countries decreased exports of sanctioned products to Russia, domestic firms in neutral countries increased these exports, driving much of the growth in sanctioned product trade.

Consumer market influences compliance, with firms exporting more to sanctioning countries reducing their sanctioned product exports to Russia, while those importing more from sanctioning countries increased sanctioned product exports.

Trade rerouting by neutral country domestic firms accounted for more than half of their sanctioned product export growth, weakening the impact of sanctions. Sanctioning MNEs also shifted exports to Russia-friendly countries, suggesting mixed compliance. Financial sanctions further reduced Russian imports in riskier sectors, as sanctioning MNEs faced higher financing costs from their headquarters’ banks.

Effective sanctions should mobilise MNEs in neutral countries, as they are more likely to comply with export sanctions and respond to financial sanctions. Future sanction success depends on discouraging neutral country domestic firms and non-sanctioning MNEs from trading with sanctioned countries, possibly through strengthened secondary sanctions and restricted market access for violators. To further isolate Russia, additional policies incentivising neutral countries to reduce imports from Russia are crucial. Our findings underscore the importance of MNEs and the extraterritorial reach of sanctions in geopolitical conflicts beyond the Russia-Ukraine war.

Authors’ note: The authors thank Siwei Wang for his excellent research assistance in preparing this column.

This article first appeared on VoxEU on September 25, 2024. Reproduced with permission.