Media reports suggest that some UK firms have started to move production abroad in anticipation of Brexit. Using data on announcements of new foreign investment transactions, this column reports evidence that the Brexit vote has led to a 12% increase in the number of new investments made by UK firms in EU27 countries. At the same time, new investments in the UK from the EU27 have declined by 11%. The results are consistent with the idea that UK firms are offshoring production to the EU27 because they expect Brexit to increase barriers to trade and migration, making the UK a less attractive place to invest and create jobs.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) has grown rapidly in recent decades, and firms can quickly redirect investment from one country to another (Görg and Krieger-Boden 2011).

Following the UK's vote to leave the EU in June 2016, there are concerns that Brexit may be leading UK firms to redirect investment to other countries. In particular, there is substantial anecdotal evidence that the threat of reduced access to the EU market after Brexit has pushed UK firms into setting up subsidiaries or acquiring companies in the remaining EU member states.

Media reports have documented that both large UK companies such as Barclays, HSBC and EasyJet, and smaller companies such as Crust & Crumb, a Northern Irish pizza maker, have invested in the EU27 in response to Brexit (The Guardian 2017, France24 2018, The Telegraph 2018, The Journal 2018).

In new research (Breinlich et al. 2019a), we study whether the anecdotal evidence of increased EU investment by UK firms is representative of a systematic change in outward FDI. The form that Brexit will take remains uncertain, but it is likely to lead to higher barriers to trade and migration between the UK and the EU. Higher trade barriers would make it more costly for UK-based firms to export to the EU. Consequently, there is an incentive for UK firms to invest in other EU countries as an insurance policy against Brexit.

We measure FDI activity through a count of announced greenfield and mergers & acquisitions (M&A) transactions. Greenfield activity refers to investments that create new establishments or production facilities from scratch, for example setting up a new factory. M&A transactions refer to the acquisition of existing facilities. Our analysis focuses on the period from 2010 to 2018, during which we observe around 100,000 transactions in total. Full details are given in Breinlich et al. (2019b).

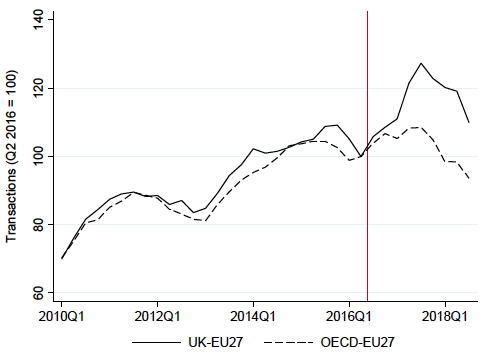

Figure 1 plots two key series in our dataset. It compares the count of quarterly FDI transactions from the UK to the EU27 with the count of transactions from non-EU OECD countries to the EU27 from 2010 to 2018, using moving averages over the two preceding and the two subsequent quarters to smooth out volatility.

The evolution of FDI into the EU27 prior to the referendum was similar for the UK and the non-EU OECD, with both series showing an upward trend until 2016. But while FDI from the non-EU OECD stagnated after 2016, FDI from the UK rose sharply in the second half of 2016 and the first half of 2017 before falling in lockstep with non-EU OECD FDI afterwards.

Source: fDi Markets and Zephyr.

Synthetic control: The doppelganger method

We employ the ‘synthetic control method’ to analyse the impact of the Brexit vote more formally (see Born et al. 2018, who use this method to estimate the effect of the Brexit vote on UK GDP). This is a way to estimate how UK FDI to the EU would have evolved after 2016Q2 if the UK had not voted for Brexit.

We construct a ‘doppelganger’ that can be interpreted as the expected trajectory of UK FDI if there had not been a Leave vote. The doppelganger is calculated as a weighted average of FDI transactions between other developed countries, with FDI in the EU from Switzerland and the US receiving the biggest weights. If the referendum outcome had no discernible impact on UK FDI behaviour, then the doppelganger and the actual series should be similar not only before, but also after the referendum.

The referendum increased foreign investment from the UK to the EU27

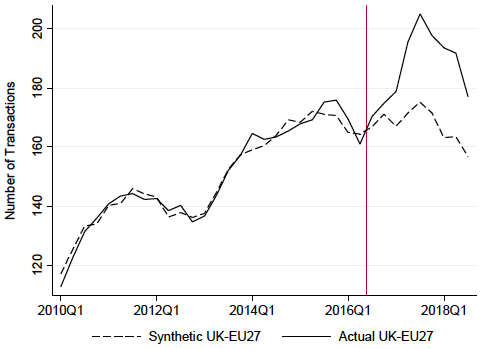

Figure 2 shows the synthetic control results. The number of FDI transactions from the UK into the EU27 goes up substantially after 2016Q2 compared to the synthetic control, which remains at 2014 and 2015 levels.

Source: fDi Markets, Zephyr and authors' calculations.

In terms of the cumulative difference between the actual and synthetic FDI series, we find that 181 greenfield and M&A transactions from the UK into the EU27 had taken place by 2018Q3 that would not have occurred in the absence of Brexit. For comparison, this increase is slightly more than the average number of quarterly FDI transactions prior to the referendum (see Figure 2). It represents a 12% increase over the level of the synthetic control.

In terms of value, we estimate these additional FDI outflows from the UK to the EU27 are worth approximately £8.3 billion in total by 2018Q3. Moreover, the persistence of the gap between the actual and synthetic series in Figure 2 shows that the referendum effect has not yet died away, meaning the increase in outward FDI due to Brexit is likely to grow further as more data becomes available.

As a note of caution, we stress that the £8.3 billion outflow can only be interpreted as ‘lost investment’ for the UK under the assumption that the investment transactions would have taken place in the UK, instead of the EU27, were it not for the Leave vote. It could also be that the referendum outcome simply triggered additional investment by UK firms in the EU27. We therefore regard £8.3 billion as an upper bound on lost investment.

Services move, manufacturing does not

Did the increase in outward FDI shown in Figure 2 occur in all sectors? We split the sample between the manufacturing and services sectors and construct a separate synthetic control for each sector.

We find a sizeable increase in outward FDI for the services sector but none for the manufacturing sector. This suggests that the aggregate effect in Figure 2 is entirely driven by services. The result is consistent with the view that the UK government has prioritised the interests of manufacturing over services in the Brexit negotiations by focusing on reducing customs frictions, while ruling out membership of the EU's single market.

No ‘Global Britain’ effect

Is the increase in FDI from the UK specific to the EU as a destination, or do we observe similar changes in UK investment flows to other countries? To evaluate this possibility, we construct a synthetic control for UK investment into non-EU OECD countries (Australia, Canada, Chile, Israel, Iceland, Norway, Japan, Mexico, New Zealand, South Korea, Switzerland, Turkey and the US).

In contrast to the EU as a destination, we do not observe an increase in UK investment activity into non-EU OECD countries. That is, UK investment in advanced economies outside Europe has not experienced a post-referendum surge. We find no sign of a ‘Global Britain’ effect.

The opposite direction: Reduced investment into the UK

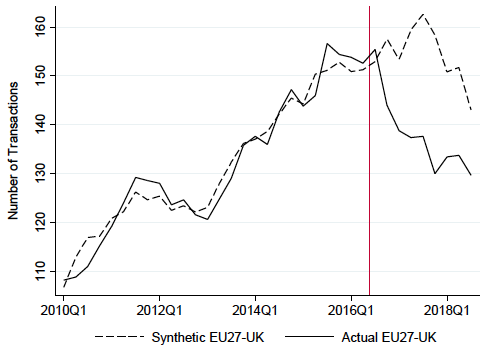

The threat of a loss of market access after Brexit could also have led to more investment by European firms in the UK. To see whether this has happened, we construct a synthetic control for FDI from the EU27 to the UK.

Source: fDi Markets, Zephyr and authors' calculations.

We display the results in Figure 3. Relative to the synthetic control, investment from the EU27 to the UK went down by around 11% after the referendum, amounting to £3.5 billion of lost investment. This finding is consistent with Serwicka and Tamberi (2018), who present evidence that the referendum led to a decline in total UK FDI inflows.

This asymmetry highlights how the UK and the EU are differentially exposed to the effects of Brexit. Put simply, because the EU is a much bigger market than the UK, access to the EU27 is more important than access to the UK.

Conclusion

We show that the Brexit vote has led to a 12% increase in the number of new investments made by UK firms in EU27 countries. The increase in UK investment in the EU27 is entirely driven by the services sector. Although it is not possible to be certain about the reasons behind firms' investment decisions, our results are consistent with the idea that UK firms are offshoring production to the EU27 because they expect Brexit to increase barriers to trade and migration, making the UK a less attractive place to do business.

By contrast, investment in the opposite direction from the EU27 into the UK has declined by 11%.

Finally, we find no evidence of a ‘Global Britain’ effect. UK firms have not increased their investment in OECD countries outside the EU27.

This article first appeared on www.VoxEU.org on February 12, 2019. Reproduced with permission.