Job reallocation is an important determinant of productivity. This column uses US data to show that a decline in the degree of job reallocation in response to shocks is behind the overall fall in the rate of reallocation over the past decades. Weakening responsiveness became a drag on aggregate productivity for high-tech businesses in the 2000s, but in other sectors the problem dates back to the 1980s.

When we think about what determines an economy's productivity, typically what comes to mind are technology, workforce skills, or management practices. But an important determinant that receives less attention is resource allocation.

Market economies continually reallocate resources, such as workers, to more efficient patterns of production and exchange. For example, behind the net job growth numbers are the flows of jobs between businesses. This job reallocation is the sum of jobs created by expanding (and entering) employers, plus jobs destroyed by those that are downsizing (and exiting). A high pace of job reallocation is costly to workers and firms, but it reflects continual movement of resources away from low-value or unproductive activities toward higher-value ones.

Distorting or slowing down this process can have a negative effect on productivity. We find evidence that this process has slowed down noticeably since the year 2000, with an implied drag on aggregate productivity.

The slowdown in job reallocation

Previous research has found a decline in the pace of job reallocation in the US since the early 1980s. Causes include changing patterns of worker turnover (Hyatt and Spletzer 2013), reduced migration (Molloy et al. 2017), an ageing work force (Engbom 2017), and less entrepreneurship (Decker et al. 2014).

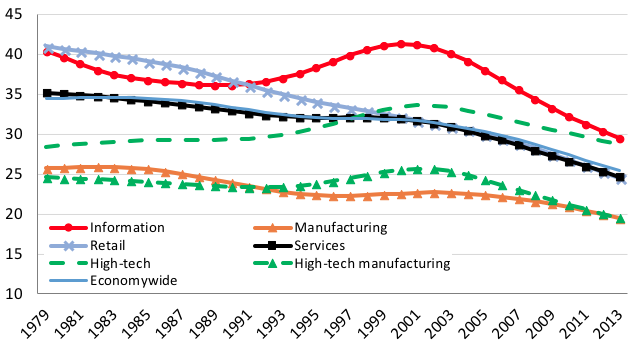

Figure 1 shows job reallocation for selected sectors. A striking feature of reallocation data, which we highlight in Decker et al. (2016), is the contrast between the overall economy, in which reallocation has declined steadily for decades, and the high-tech sector, where reallocation was flat or rising before it began declining in the 2000s.

Note: HP trends using parameter set to 100. Industries defined on a consistent NAICS basis. High-tech defined as in Hecker (2005). Includes all new entrants, continuers, and exiters.

Job reallocation is costly for firms and workers, so a decline in reallocation may improve welfare. In the retail sector, for example, the shift from ‘mom and pop’ firms to retail chains has led to greater firm stability and higher productivity. Other shifts in business model may have similar effects. On the other hand, evidence suggests that much reallocation is increases productivity, so whether the patterns of reallocation in Figure 1 have been detrimental to productivity depends on what caused them.

Explaining the decline

In recent research (Decker et al. 2018), we shed light on this question by applying insights from canonical models of firm dynamics with adjustment frictions. These models propose two alternative hypotheses for explaining the decline in job reallocation:

- Fewer or less-intense shocks. Each business responds to shifts in productivity and profitability conditions or opportunities. This response includes job creation and destruction. A decline in reallocation could therefore mean the dispersion or intensity of idiosyncratic shocks faced by businesses has declined too. Idiosyncratic shocks might reflect different realisations of technical efficiency or relative demand for products across producers. A decline in the dispersion of these shocks might be roughly benign for overall productivity. It may even increase welfare by reducing the need for workers and firms to make costly changes.

- Increasing costs and frictions. Since the pace of reallocation reflects the responsiveness of businesses to their environment, an increase in costs or frictions that inhibit business expansion or contraction will reduce overall reallocation. If reallocation declines for this reason, this is likely to reduce living standards, because it traps resources in unproductive businesses.

Standard models provide convenient empirical predictions that allow us to distinguish between these alternative hypotheses:

- Holding frictions constant, a decline in the dispersion of shocks implies lower dispersion of measures of business-level productivity, such as revenue per worker.

- A rise in labour adjustment frictions implies a weaker relationship between employment growth and productivity at the business level, and also an increase in dispersion of revenue per worker across businesses. If productive businesses become less likely to add workers and unproductive businesses become more likely to hoard workers, revenue per worker rises for productive firms and declines for unproductive firms, increasing overall dispersion.

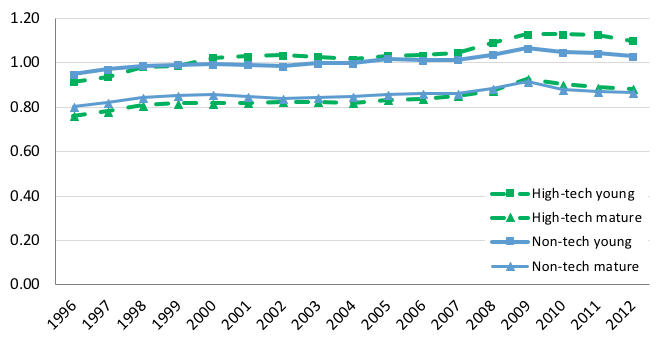

Figure 2 shows the standard deviation of firm-level revenue per worker for young and mature high-tech and non-tech firms in the US. Labour productivity dispersion has been gradually increasing. We also use manufacturing data starting in the 1980s that show gradually rising total factor productivity (TFP) dispersion (Note 1).

Note: Standard deviation of log labour productivity deviated from industry-by-year means. Young firms are less than five years old. High-tech is defined as in Hecker (2005). NAICS 52 and 53 omitted.

If dispersion of productivity across firms has risen, this contradicts the hypothesis that the dispersion of shocks has changed and supports the hypothesis that the responsiveness of businesses has weakened.

Investigating the decline in responsiveness

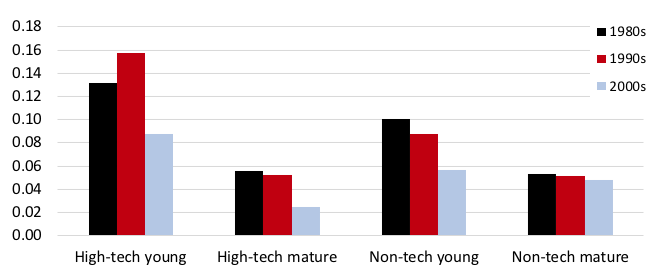

We focus on the manufacturing sector, constructing estimates of TFP at the establishment level to study the employment growth responses of businesses. Figure 3 shows the employment growth response differential between high-productivity establishments—those that are one standard deviation above the mean within their industry—and establishments at the industry average for productivity.

We calculate this for different types of businesses (young and mature, high-tech and non-tech) and different time periods (1980s, 1990s and 2000s). During the 1990s, employment in establishments of high-tech young firms that were one standard deviation above their industry's TFP average grew by 16 percentage points more in a year than the industry average.

More generally, productivity responsiveness among high-tech businesses rose from the 1980s to the 1990s then fell during the 2000s, mimicking the pattern of job reallocation in the high-tech sector over the same period that we saw in Figure 1. Outside high-tech, productivity responsiveness declined throughout the period, consistent with the aggregate reallocation series. This supports for the responsiveness hypothesis.

Note: Young firms are less than five years old. High-tech is defined as in Hecker (2005). Growth rate of plant with TFPR one standard deviation above industry mean vs industry mean.

Rising labour adjustment costs and frictions are not the only potential explanation. An increase in market power of firms or rising prevalence of winner-takes-all competition would be likely to reduce responsiveness, but it would not affect productivity dispersion in standard models. If technological diffusion across firms was slower (as argued by Andrews et al. 2015), this may produce rising dispersion of output per worker, but slower diffusion alone would not explain weakening business-level responsiveness.

The effect on productivity

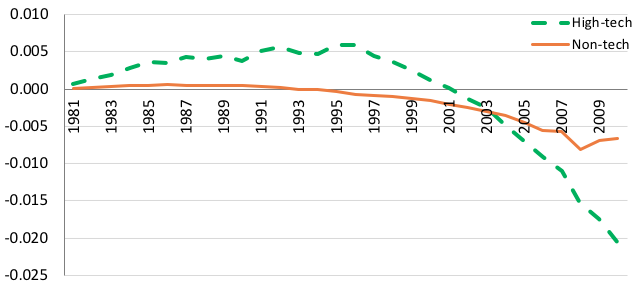

Weakening responsiveness implies slower flows of resources to productive businesses, a significant implication for aggregate productivity. We conduct a simple counterfactual to estimate the magnitude of these productivity effects. Using our business-level microdata, for each year we estimate the aggregate productivity from the estimated responsiveness coefficients in Figure 3. Then we compare this aggregate estimate with an estimate in which productivity responsiveness was held constant at its strength in the early 1980s. There is higher aggregate productivity in the ‘constant responsiveness’ scenario by the end of the period, because it allows the most productive businesses to acquire more resources. Figure 4 shows the difference between these scenarios, for both high-tech and non-tech manufacturing.

Note: Figure depicts diff-in-diff counterfactual from TFPR concept. High-tech is defined as in Hecker (2005).

To interpret Figure 4, consider the high-tech line in 2010. The value of -0.02 implies that, given the actual distribution of establishments' size and productivity in 2009, aggregate (industry) productivity in 2010 would have been about 2% higher if productivity responsiveness were still at 1980 rates.

More generally, the line for high-tech is positive during the 1980s and 1990s, as responsiveness rose (see Figure 3). Rising responsiveness was boosting productivity through improved job allocation. In the 2000s, declining responsiveness became a drag on aggregate productivity.

This timing is similar to the timing of US productivity growth generally. Fernald (2014) documents the productivity acceleration of the late 1990s and slowdown of the mid-2000s, which was concentrated in IT-using and producing industries.

We also find similar results for non-manufacturing industries (based on labour productivity instead of TFP). Moreover, within high-tech manufacturing we find that the responsiveness of capital investment and establishment exit follow similar patterns, suggesting that the trend of weakening productivity selection is general, and we find that the change in responsiveness was not the result of composition effects. We find no evidence that this slowdown in reallocation-driven productivity growth has been offset by stronger within-firm productivity growth.

Adjustment frictions

Discovering the cause of changing patterns of job reallocation is important. These patterns have significant implications for aggregate productivity and living standards. Our investigation suggests that researchers should focus on potential sources of rising adjustment frictions. These could include any policies or other factors that raise the cost of, or reduce the incentive for, hiring and downsizing.

Authors' note: We thank Cathy Buffington for helpful comments. Any opinions and conclusions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the US Census Bureau or of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System or its staff. All results have been reviewed to ensure that no confidential information is disclosed.

This article first appeared on www.VoxEU.org on July 12, 2018. Reproduced with permission.