Economic inequality has increased in many countries over the past two decades and generated increased public concern. Globalization opponents allege that the activities of multinational corporations directly contribute to increasing economic inequality. Proponents of globalization typically deflect such criticism by pointing to aggregate gains from international trade or other causes of inequality, such as technological change, that may play a larger role. To examine the relationships between multinationals, foreign direct investment (FDI), trade, and inequality, we invited economists from the Asia-Pacific region to participate in a research project entitled "Trade, Growth and Economic Inequality in the Asia-Pacific Region (Note 1)." One part of this project focused on FDI's potential impact on inequality in host countries (i.e., countries receiving the FDI inflows) (Note 2). We briefly summarize the research findings of two of the project papers below, and note that all of the 11 conference papers appear in a special issue of the Journal of Asian Economics (February 2017).

Theories on FDI and inequality

To begin to examine the effects of FDI, we first need to examine why firms invest abroad. Early explanations for FDI relied on the capital arbitrage hypothesis, wherein capital owners seek higher rates of return abroad. When factor returns (e.g., capital returns, worker wages) do not equalize through international trade alone, we expect to see capital flows from countries with relative capital abundance to those with relative capital scarcity. Another way to express these flows would be capital flows from its home market with labor scarcity, and accompanying high wages, to a host market with labor abundance and lower wages. The capital arbitrage hypothesis would predict gains for capital owners in the home country—both overseas investors and non-overseas investors—and for labor in the host country. However, most FDI flows into developed countries rather than developing countries so other hypotheses have been developed to cover the apparent weakness of the capital arbitrage hypothesis to explain these flows (Note 3).

To accommodate different motivations for different types of FDI flows, economists have developed theories of vertical versus horizontal FDI. Vertical FDI involves breaking up the production process into separable pieces and locating one or more production steps abroad, while horizontal FDI involves replicating a firm's production activities overseas. Vertical FDI typically is motivated by cost differences across countries, and often involves flows from developed to developing countries. The distributional effects of vertical FDI are expected to be similar to the capital arbitrage hypothesis discussed above since factor cost differences motivate the capital flows in both cases. Explaining horizontal FDI involves a "proximity-concentration tradeoff" where FDI flows can occur between developed countries and, in recent years, between developing countries. Locating closer to a firm's customers involves proximity advantages such as lower transportation costs and/or avoiding trade barriers, at a potential cost of lost scale economies in duplicating the firm's production facilities in more than one location.

Distributional effects (i.e., winners and losers within a country) are difficult to predict with horizontal FDI that typically occurs between countries with similar factor endowments and factor prices. For this reason, horizontal FDI usually causes less concern than vertical FDI among home country workers. Therefore, our studies focused on vertical FDI or on offshoring broadly defined to include locating parts of the production process in lower-cost countries, regardless of whether an equity linkage exists between the buying and supplying firms. Developing country workers often welcome FDI inflows that provide job creation and wage premiums paid by foreign firms relative to domestic firms. However, multinationals often locate only in specific regions within a country with access to ports, other transportation infrastructure, and/or preferential government policies (e.g., free trade zones), so whatever benefits derive to local workers may be limited to a specific geographic region. If workers are somewhat immobile geographically within their home country, FDI may exacerbate intracountry regional inequality.

Effects on host countries

Greaney and Li (2017) examine whether regional income inequality in China can be linked to regional differences in receiving FDI inflows. Do multinationals enterprises (MNEs) tend to locate in more advanced regions with better infrastructure and higher wages or do they gravitate toward lower-wage regions? We find that foreign-direct-invested enterprises (FDIEs) tended to have the largest shares of industrial output in eastern provinces, such as Shanghai at 46.8% and Beijing at 32.2%, and the lowest shares in western provinces, such as Gansu at 1.3% and Ningxia at 1.9%, in 2013. Multinationals owned by overseas Chinese investors (i.e., Hong Kong, Macao or Taiwan-invested enterprises, or HMTEs) accounted for the largest shares of industrial output in the eastern provinces of Guangdong (22.9%) and Fujian (22.3%), and the lowest shares in the western provinces of Gansu (0.4%), Ningxia and Guizhou (both at 0.9%). The closer proximity to port facilities and to other manufacturers in the east seem to outweigh the higher salaries in those provinces relative to the western provinces.

In 1999, China's provinces were highly unequal in their hosting of HMTE activities, but interprovincial inequality declined steadily until 2013. Interprovincial inequality in FDIE activities was much lower than that for HMTEs in 1999, increasing slightly through 2004, then declining a bit until 2009 and increasing slightly through 2013. Interprovincial wage inequality increased somewhat from 1999 to 2003, but it declined steadily and by a larger amount from 2003 to 2013. Dividing China's 28 provinces into four regions—east, northeast, central and west—we find that intraregional inequality has played a larger role than interregional inequality in total interprovincial inequality since 2006.

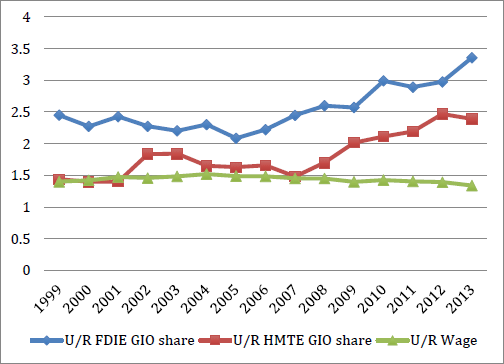

When each province is divided into urban versus rural areas, we find that overall urban-rural wage inequality increased slightly from 1999-2003 but then declined steadily from 2003-2013, as shown in Figure 3 (Note 4). MNEs have a strong and increasing tendency to locate in urban rather than rural areas. The urban-rural gap in MNE activities is higher for FDIEs than for HMTEs, with both types of foreign firms becoming more concentrated in the urban parts of China over time. We tested for a relationship between urban-rural wage inequality and MNE activities but conclude that neither provincial MNE activities nor the concentration of MNE activities in urban areas significantly affect urban-rural wage inequality. The factors driving this type of inequality over recent years appear to be rural-to-urban labor migration and wage growth, both of which contribute toward lowering this type of inequality in China.

McLaren and Yoo (2017) examine the effect of FDI in Vietnam, utilizing household level census data between 1989 and 2009. Vietnam had a big transformation from a closed and centrally-planned economy to an open and market-based one starting in the late 1980s and has received a substantial amount of FDI, especially from Japan. Employment shifted from agriculture to manufacturing and services, and the country experienced significant economic growth. Against this backdrop, the authors analyzed the effect of FDI inflows at the provincial level on the living standards of households since they did not have wage data. They relied on welfare measures such as access to electricity, water, and toilets; living area; television set ownership; and child mortality. They find that hiring by multinationals in a province may slightly reduce living standards even if the household has a member working for a foreign company, but the results vary by different welfare measures and econometric specifications. For example, the household may be more likely to have a larger living area and lower child mortality but less likely to have access to electricity or own a television set. Although the small negative effect on living standards appears to be in contrast with Greaney and Li's findings, McLaren and Yoo find no clear pattern in the differences for urban versus rural areas which is in line with Greaney and Li. Moreover, they also find some evidence for increased migration to provinces with larger FDI inflows in Vietnam which indirectly suggests potential welfare benefits of FDI in contrast with their micro-level findings. They referenced several other studies that have found strong welfare benefits for Vietnamese households from increased export opportunities in concluding that seeking similar evidence related to inward FDI may be empirically more challenging due to the endogeneity of FDI flows and difficulty in identifying appropriate instruments.

Conclusions

These two research papers, together with our nine other project papers, demonstrate that the linkages between international trade, multinationals, FDI, and inequality are complex, but different approaches, data sets, and experiences of countries provide us with a fuller picture. The papers displayed mixed and sometimes contrasting results which is evidence that there is no single theory or recipe that fits all cases and that it is important to unpack the different channels linking these economic forces and outcomes. There are nuances and subtleties in these relationships as the studies emphasized. We need to take advantage of various trade theories based on comparative advantage, heterogeneous firms, and heterogeneous workers as well as study particular channels through which trade and FDI impact economic growth and inequality. This approach provides the best outlook for making progress in our understanding of these fundamental economic development challenges.