Economics, and economists, are often accused of insularity and hubris, and of talking primarily to themselves in their research. This column uses a recent analysis of citations to and from other disciplines to show that this is no longer the case. Economics papers increasingly cite non-economic research, and other disciplines cite economists more often too. The data suggest that the rising quantity and quality of empirical research in economics has increased the relevance of the field to non-economists.

The 2017 Nobel in Memorial Prize Economic Sciences, awarded to University of Chicago's Richard Thaler, has given behavioural economics well-deserved recognition. Thaler and colleagues are fascinated by differences between economists' benchmark model of rational decision-making and the seemingly irrational decisions that psychologists hope to explain. Behavioural economists work in the space between these two social sciences. This intersection is a recent development: as Camerer (1999) observed, "[E]conomists routinely—and proudly—use models that are grossly inconsistent with findings from psychology."

Some hold the opinion that the distance between economics and other social sciences reflects the insularity and hubris of economists. Fourcade et al. (2015) argued that academic economics is characterised by a self-serving sense of superiority that reflects the guild-like structure of our discipline (two of the three authors are sociologists). Thaler's prize reminds us that economics is the only social science for which there is a Nobel. Many economists claim the ear of kings and princes, and most have plenty of outside opportunities to make a buck. Following the Great Recession, this has prompted external critics of the discipline (and some from within, like Zingales 2013) to ask whether our mission of pure scholarship has been corrupted or devalued.

A lonely island?

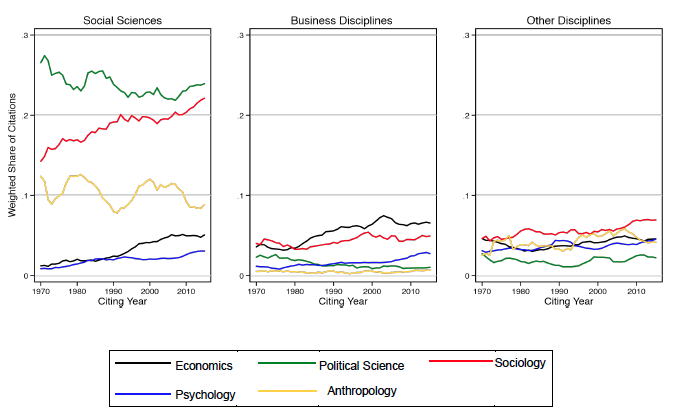

Our recent paper looking at ‘extramural citations’ attempts to gauge the scientific standing of academic economics research (Angrist et al. 2017a). We find that the polemical claims that economics is an insular social science are out of date. Economics pays less attention to other social sciences than do political science and sociology—but Figure 1 shows that, since around 1990, this insularity has declined. Economists are now more likely than psychologists to cite other social science disciplines (left-hand panel).

Measured by citations to non-social-science disciplines, economics looks even less insular. The centre panel shows that economists are more likely than other social sciences to cite business disciplines (finance, accounting, marketing, and management) and are at least as likely to cite a group of seven other disciplines as three out of four of other social sciences (right-hand panel).

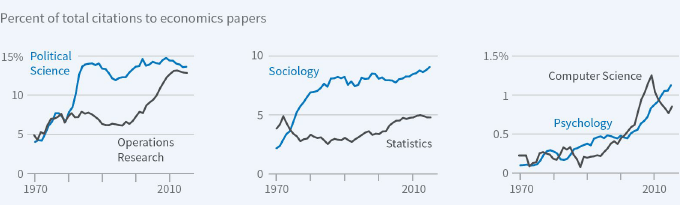

We also find that, since 1990, economics has been especially and increasingly attentive to political science. Behavioural economics is grounded in psychology, but the flow of influence runs both ways. Figure 2 (right-hand panel) shows that psychology's citation rate of economics papers, while still low in absolute terms, has more than doubled since the early 2000s.

Citations in computer science and operations research have also grown rapidly (Figure 2, right-hand panel). Our analysis also shows that political science and sociology citations to economics grew rapidly in the 1970s and 1980s. Sociology has been citing economics more than it cites political science or psychology since the late 1970s. Among the social sciences, only anthropology has remained distant.

Change from within

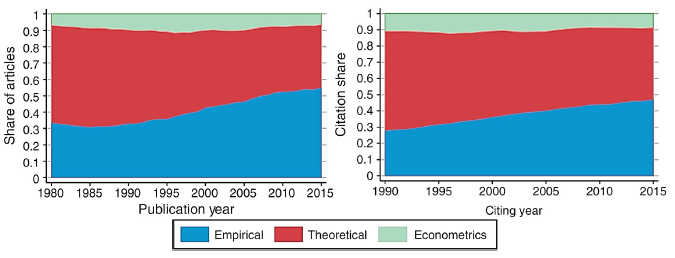

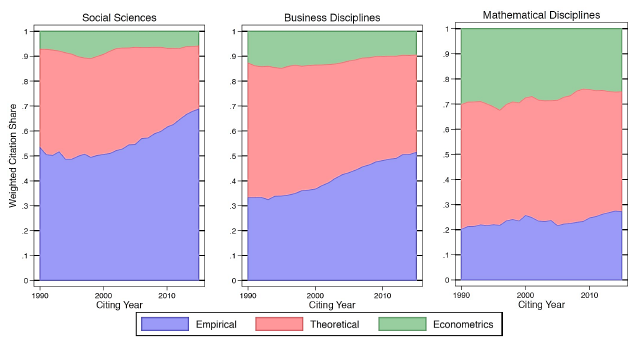

This growth in the extramural influence of economics reflects an important change within. Through the early 1990s, economic theory took pride of place, garnering more intramural citations and appearing more often than empirical work in our top journals. Our study of the evolution of fields and styles in economic research (Angrist et al. 2017b) shows, however, that recent decades have seen the share of economics' citations to empirical work grow steadily. Cites to empirical work now account for about half of citations in top economics journal publications. We discovered this by using a machine-learning algorithm that reads abstracts, titles, keywords, and references to classify economics into three research styles, empirical, theoretical, and econometric theory. Figure 3, below, documents the empirical shift in economics publications and in intramural citations.

This move towards empiricism probably reflects what Angrist and Pischke (2010) called the "credibility revolution" in economic research. Empirical economics gets more attention now because its quality has increased, and so the work is more credible and convincing, and more likely to be discussed, challenged, and replicated in later work. In short, it has become more scientific.

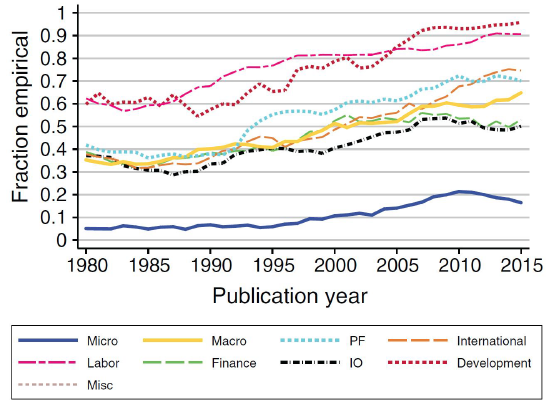

The shift towards empirical work in economics is widespread. Figure 4 plots empirical shares of citations by economics field (we also used a machine learning algorithm to classify economics papers into fields, like IO, labour, and macro). In the early 1980s, only development and labour economics had a majority of their citations go to empirical work. The weighted empirical share has since grown in all fields. It now exceeds 90% in these two fields. Even macroeconomics, criticised after the great recession for an excess of ivory-tower theorising, has seen its empirical share grow by more than 50%. In most fields, the trends reflect both increasing numbers of empirical papers, and the generally improved journal placement of empirical work.

Strength in diversity

The rise in the extramural influence of economics scholarship has been accelerated by the diversity of research. Most disciplines cite papers from more than one field of economics, and the fields of primary interest vary across disciplines. Labour economics is the most cited field in sociology, while computer scientists tend to reference micro. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, political science reads political economy. There are almost as many focal fields as disciplines.

Empirical work has been drawing a greater share of attention from most of the disciplines in which economics is important. The left-hand and centre panels of Figure 5 show the strong growth in empirical research citations in social science and business disciplines. In psychology (recall Thaler), public health, medicine, and multidisciplinary science, the rise in the extramural influence of economics coincided with the growing share of citations to empirical work. This is consistent with the idea that empirical work caused increased citation rates.

In other cases, including political science and sociology, the rise in the empirical share of citations came after economics became influential. In these fields, the rise of empirical work may have allowed economics to remain influential, even as interest in theoretical economics waned.

The theory-empirical pattern is not universal. Heightened interest in economics in operations research and computer science, which also started around 2000, reflects these fields' enduring interest in economic theory. Citations to empirical work have increased in the mathematical disciplines we studied (OR, statistics, computer science, and mathematics), but the majority of citations there were still to economic or econometric theory. This suggests again that the diversity of economics is a source of strength.

We find little evidence in citation statistics to support the notion that economics is intellectually isolated. Instead, we find growing links between economics and a wide range of other disciplines. This reinforces our view that economic scholarship has never been more exciting or useful than it is today.

This article first appeared on www.VoxEU.org on November 17, 2017. Reproduced with permission.