Recent research has shown that industrial robots have caused severe job and earnings losses in the US. This column explores the impact of robots on the labour market in Germany, which has many more robots than the US and a much larger manufacturing employment share. Robots have had no aggregate effect on German employment, and robot exposure is found to actually increase the chances of workers staying with their original employer. This effect seems to be largely down to efforts of work councils and labour unions, but is also the result of fewer young workers entering manufacturing careers.

The fear of an imminent wave of technological unemployment is again one of the dominant economic memes of our time. The popular narrative often goes as follows—as software and artificial intelligence advance, production processes (especially in manufacturing) become increasingly automated. Workers can be replaced by new and smarter machines—industrial robots, in particular—which are capable of performing the tasks formerly carried out by humans, faster and more efficiently. The robots will therefore make millions of workers redundant, especially those with low and medium qualifications, and reshape society in a fundamental way.

There have been dramatic estimates of how many occupations are at risk of being automated, given the type of work they usually conduct (e.g. Frey and Osborne 2017). But until very recently, there has been little systematic analysis about the general equilibrium impact of robots and other new technologies. Acemoglu and Restrepo (2016, 2017) show that this equilibrium impact is, in fact, ambiguous theoretically. Robots directly substitute workers when holding output and prices constant, but the resulting cost reductions also increase product and labour demand. Moreover, workers can be soaked up by different industries, and specialise in new and complementary tasks.

Acemoglu and Restrepo develop an estimation approach from their theory, and apply it to local labour markets in the US (1993-2014). The empirical picture that emerges seems to confirm some of the darkest concerns. Specifically, they find that one additional robot reduces total employment by around three to six jobs. It also reduces average equilibrium wages for almost all groups in the labour market. So, displacement effects caused by robots seem to be widely dominant in the US.

Germany: The land of robots and manufacturing workers

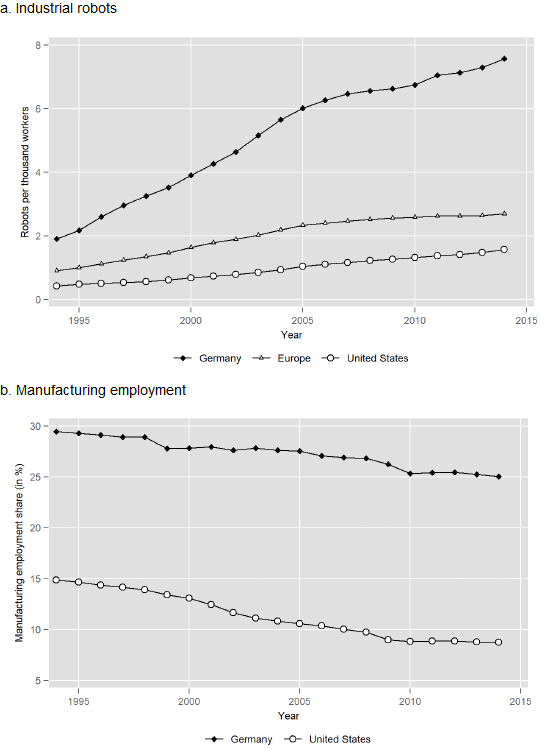

In a recent paper, we consider the impact of robots on the German labour market (Dauth et al. 2017). Robots are much more prevalent in Germany than in the US or elsewhere outside Asia. Figure 1 shows that almost two industrial robots were installed per thousand workers in Germany in 1994, more than twice as many as the European average and four times as many as in the US. Usage almost quadrupled over time, and now stands at 7.6 robots per thousand workers compared to only 2.7 and 1.6 in Europe and the US, respectively. But despite the fact that there are many more robots around, Germany is still among the world's major manufacturing powerhouses with an exceptionally large employment share. It ranges around 25% in 2014 (compared to less than 9% in the US), and has declined less dramatically over the last 25 years (see the bottom panel in Figure 1).

Moreover, Germany is not only a heavy user but also an important engineer of industrial robots. The ‘robotics world rankings’ list eight Japanese firms among the ten largest producers in the world; the remaining two (Kuka and ABB) have German origins with production mostly in Germany. Among the 20 largest firms, five are originally German and only one (Omron) is from the US. Our analysis for Germany thus elicits the causal labour market effects of robots in a context with many more manufacturing jobs per capita than could potentially be replaced, but also with many more robots installed in production and robotic producers located close by.

Aggregate employment effects of robots

For our analysis, we exploit the same dataset from the International Federation of Robotics (IFR) that was used by Acemoglu and Restrepo (2016, 2017) and in the pioneering study by Graetz and Michaels (2017). It reports the number of robots installed in 25 industries and 50 countries over the period from 1994 until 2014. For Germany, data coverage is comprehensive, and we find that by far the largest increase in installed robots occurred in the various branches of the automobile industry. Here, 60-100 additional robots were installed per thousand workers in 2014 compared to 1994. Other industries that became vastly more robot-intensive include furniture, domestic appliances, and leather. On the other side of the spectrum, we find cases where robot usage has hardly changed, for example in services.

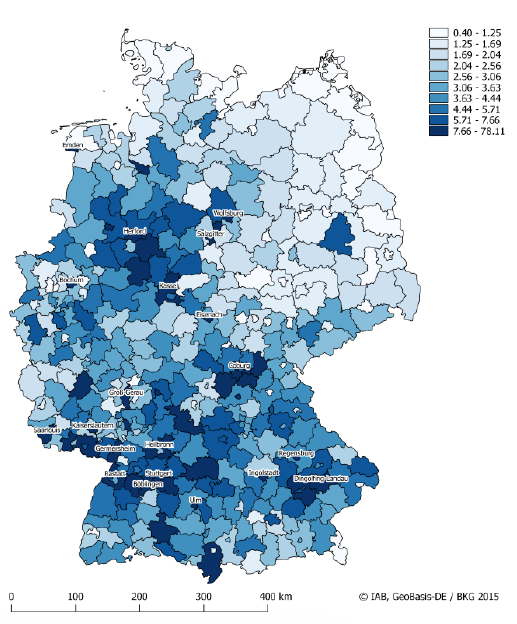

From these industry-level data, we construct a measure of local robot exposure, which reflects the industry mix across German regions. This is illustrated in Figure 2. The map indicates that robot exposure in East Germany is lower, which reflects the smaller overall manufacturing share there. Within West Germany, values range from close to zero up to 78.1 additional robots per thousand workers, a variation that is much stronger than in the US.

We regress total local employment growth on this measure of robot exposure. We find no evidence for negative effects like those in the US. The raw correlation between robots and growth is even positive, but this is strongly driven by the automobile industry. Once industry structures and demographics are taken into account, we find effects close to zero, both in simple ordinary least square regressions and in more sophisticated instrumental variable estimations.

Although robots do not affect total employment, they do have strongly negative impacts on manufacturing employment in Germany. We calculate that one additional robot replaces two manufacturing jobs on average. This implies that roughly 275,000 full-time manufacturing jobs have been destroyed by robots in the period 1994-2014. But, those sizable losses are fully offset by job gains outside manufacturing. In other words, robots have strongly changed the composition of employment by driving the decline of manufacturing jobs illustrated in Figure 1. Robots were responsible for almost 23% of this decline. But they have not been major killers so far when it comes to the total number of jobs in the German economy.

The effect of robots on individual workers

These aggregate empirical findings raise questions about how, and through which channels, robots affect individual workers. To shed light on this previously unexplored issue, we use linked employer-employee data which trace employment biographies and earnings profiles of roughly 1 million manufacturing workers with varying exposure to robots (and some other technology and trade shocks) over time. This analysis is, to the best of our knowledge, the first in the literature to comprehensively address how individual workers were affected by and responded to the rise of robots.

This worker-level analysis delivers a surprising insight—we find that more robot-exposed workers in fact have a substantially higher probability of keeping a job at their original workplace. That is, robot exposure increased job stability for these workers, although some of them end up performing different tasks in their firm than before the robot exposure.

The negative equilibrium effect of robots on aggregate manufacturing employment is therefore not brought about by direct displacements of incumbent workers. It is instead driven by smaller flows of labour market entrants into more robot-exposed industries. In other words, robots do not destroy existing manufacturing jobs, but they do induce firms to create fewer new jobs for young people.

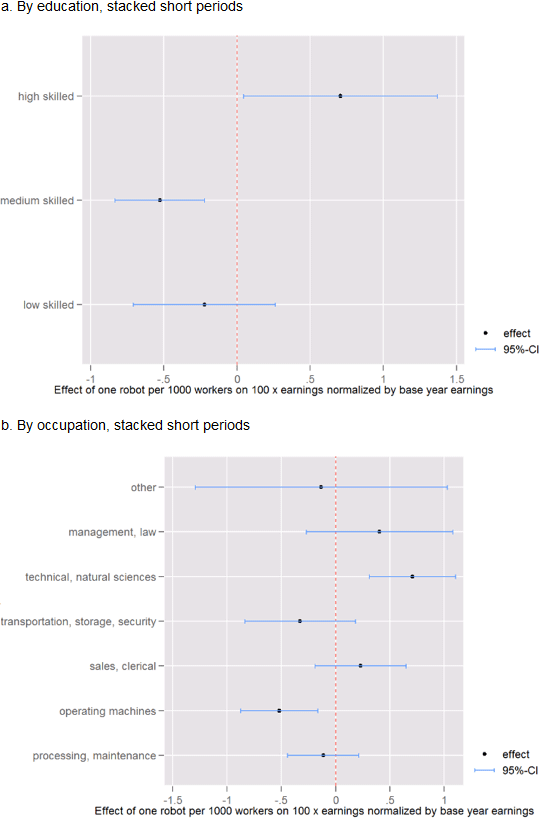

When it comes to the wage and earnings effects of robots, we find considerable heterogeneity at the individual level. These results, illustrated in Figure 3, provide evidence at the micro level that robots are a form of skill-biased technological change.

Robot exposure causes notable on-the-job earnings gains for high-skilled workers, especially in scientific and management positions. Those workers may gain from robots, because they possess complementary skills to this technology and perform tasks that are not easily replaceable. But for low-skilled and especially for medium-skilled manufacturing workers, we find sizable negative impacts. Completed apprenticeship is the typical profile for manufacturing workers in Germany, and this group of medium-skilled workers accounts for almost 75% of all individuals in our sample. They are overrepresented in manual and routine-intensive occupations, such as machine operators, which may become somewhat obsolete, because robots—by definition—do not require a human operator anymore but have the potential of conducting many production steps autonomously. Those workers suffer from lower wages and cumulative earnings losses caused by robots, but even for them we find no increased displacement risk, rather positive employment effects.

Aggregate effects of robots on productivity and the labour share

We believe that those empirical findings reflect a key feature of industrial relations in the German labour market—the manufacturing sector is still highly unionised, and blue-collar wages (especially) are typically determined collectively with strong involvement of work councils. It has been frequently argued that German unions have a strong preference for maintaining high employment levels, and are willing to accept flexible wage setting arrangements, such as opening clauses, in the presence of negative shocks in order to keep jobs. This flexibility of unions, and the resulting wage restraints, are actually seen as one of the leading hypotheses for the strong overall performance of the German labour market (the ‘employment miracle’) since the mid-2000s (e.g. Dustmann et al. 2014).

Our analysis suggests that the rise of the robots may have triggered a similar response, namely the willingness of insiders to swallow wage cuts in order to stabilise jobs in view of the threat posed by robots. This channel is of lesser importance for high-skilled managers and comparable employees with flexible contracts. But it seems to be very relevant for medium-skilled workers.

Finally, in the aggregate we find that robots raise average productivity and total output net of the wage bill, but not average wages. In other words, our analysis suggests that robots have contributed to the decline of the labour income share (Autor et al. 2017, Kehrig and Vincent 2017). Most rents from this new technology seem to be captured by profit claimants and capital owners. For them, as well as for skilled workers with high levels of human capital, robots have been friends in the labour market. But for the bulk of low- and medium-skilled workers, the relationship is more difficult.

Overall, we conclude that robots have not been major job killers in Germany so far, somewhat in contrast to the buzz in some of the contemporary public debate. But they do induce notable distributional shifts. Compared to the US, it seems that the reaction of the German labour market has been more friendly, not only to the ‘China shock’ (Dauth et al. 2014, Marin 2017), but also to the rise of robots.

This article first appeared on www.VoxEU.org on September 19, 2017. Reproduced with permission.