| Author Name | Willem THORBECKE (Senior Fellow, RIETI) / CHEN Chen (Fuzhou University of International Studies and Trade) / Nimesh SALIKE (Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University) |

|---|---|

| Research Project | Economic Shocks, the Japanese and World Economies, and Possible Policy Responses |

| Download / Links |

This Non Technical Summary does not constitute part of the above-captioned Discussion Paper but has been prepared for the purpose of providing a bold outline of the paper, based on findings from the analysis for the paper and focusing primarily on their implications for policy. For details of the analysis, read the captioned Discussion Paper. Views expressed in this Non Technical Summary are solely those of the individual author(s), and do not necessarily represent the views of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI).

In 2024, China’s exchange rate against the U.S. dollar (USD) is close to its weakest level since 2008. At the same time, rising exports from China are generating protectionist pressures in the U.S., the European Union, and other trading partners. Does a weak renminbi stimulate China’s exports?

Traditional models indicate that a depreciation of the exporting country’s currency against the importing country’s currency can lower import prices in the importing country’s currency. This can in turn raise imports flowing into the country.

Recently the IMF (2019) has challenged these traditional models. They noted that USD invoicing plays a dominant role in trade, even when countries are trading with each other and not with the U.S. For trade invoiced in USD between two countries other than the U.S., a depreciation of the exporting country’s currency relative to the importing country’s currency will not increase the importing country’s purchasing power in USD and not enable it to import more. An appreciation of the importing country’s currency relative to the USD, on the other hand, will enable it to purchase more imports. This approach is called the dominant currency pricing (DCP) framework.

China’s exports were largely invoiced in USD, especially before 2012. The IMF (2019) reported that, on average over the 2001-2015 period, more than 90% of China’s exports were invoiced in USD. Georgiadis et al. and others reported that, after 2011, the share of China’s exports invoiced in renminbi increased.

Several researchers have presented evidence supporting the DCP framework. For instance, Boz et al. (2022) examined the impact of exchange rates on trade volumes for 2,847 dyads over the 1990-2019 period. When only including the bilateral nominal exchange rate between the exporting and importing countries and control variables, they reported that a 1% depreciation increases exports by 0.1%. When the importing country’s nominal exchange rate relative to the USD is also included in the regression, the coefficient for the bilateral exchange rate falls to 0.04% in one specification and ceases to be statistically significant in another. A 1% appreciation of the importer’s currency relative to the USD, on the other hand, now increases imports by between 0.2% to 0.5%.

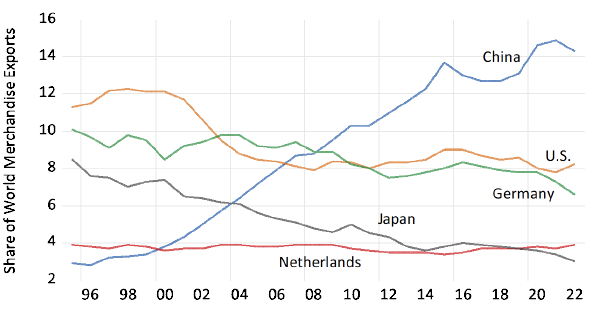

This paper investigates whether traditional models or the DCP framework provides a better explanation for China’s export volume. Much of the previous work investigating DCP models has not included China because the Chinese government does not provide invoice data for trade. Figure 1 shows that China since 2007 has been the world’s leading exporter. Its exports in 2021 and 2022 equaled exports from the next two leading exporters, the U.S. and Germany, combined. Investigating whether the DCP paradigm provides a good explanation for China’s exports is thus important.

The results indicate that over the 1995-2018 period both the bilateral RMB real exchange rate between China and the importing countries and the USD exchange rate relative to the importing country are important for explaining China’s exports. However, when the sample is restricted to the 1995-2011 period when USD invoicing of exports prevailed, the bilateral exchange rate retains explanatory power but the USD exchange rate relative to the importing country no longer matters. These findings are contrary to the predictions of the DCP model.

We also investigate individual categories of Chinese exports such as computers, footwear and sweaters. The results remain unfavorable to the DCP framework.

How can we understand these findings? During the 1995-2011 period, Chinese exporters faced severe credit constraints (see Manova and Yu, 2017). An increase in RMB revenues would ease these constraints. When the RMB depreciates against the importing country, importing firms would be able to pay more renminbi without losing revenues in their own currencies. Did cash-strapped Chinese exporters change the dollar value of exports often enough to exploit these gains from trade?

Also, unlike for other countries, we do not have government data on the share of Chinese exports invoiced in different currencies. Could it be that the share of exports invoiced in dollars was less than what other sources suggest?

Another possibility is that the findings reflect the pervasive influence of MNCs in China’s exports during the earlier sample period. As Ito et al. (2018) discussed, many MNCs managed currency risk at their global headquarters. This gave them flexibility to choose different invoicing currencies at different times and with different countries. Did the invoicing patterns of MNCs allow bilateral exchange rate to matter over the earlier sample period? Future research should consider whether credit constraints, the role of MNCs, or other factors can help explain why bilateral exchange rates, rather than USD exchange rates relative to importing countries’ currencies, mattered so much for China’s exports.

- Reference(s)

-

- Boz, E., Casas, C., Georgiadis, G., Gopinath, G., Le Mezo, H., Mehl, A., Nguyen, T. 2022. Patterns of Invoicing Currency in Global Trade: New Evidence. Journal of International Economics 136, 103604.

- Georgiadis G., Le Mezo, H., Mehl, A., Tille, C. 2021. Fundamentals vs. Policies: Can the US Dollar’s Dominance in Global Trade be Dented? ECB Working Paper Series No. 2574. European Central Bank, Frankfort.

- IMF. 2019. External Sector Report: The Dynamics of External Adjustment, Chapter 2. International Monetary Fund, Washington DC.

- Ito, T., Koibuchi, S., Sato, K., Shimizu, J. 2018. Managing Currency Risk: How Japanese Firms Choose Invoicing Currency. Edward Elgar Publishers, Cheltenham, UK.

- Manova, K,, and Yu, Z., 2017. Multi-product Firms and Product Quality. Journal of International Economics 109, 116-137.