PDF version [PDF:193KB]

The need for work style reform

The work style of the Japanese people has recently become a focus of attention as never seen before. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe reshuffled his Cabinet in August 2016 and placed work style reform of the Japanese people as a central challenge, appointing a minister in charge of work style reform and establishing the Council for the Realization of Work Style Reform. Businesses and labor unions have also picked up on these developments and have been working towards accommodating a new work style that can match the future working environment.

Why does Japan need to reform its work style now? In economics, which is my own field of expertise, businesses and workers are thought to always act rationally. Therefore, in principle, no problems arise with the work style of employees at businesses, and under this principle, a work style that produces optimal performance is always achieved. This perception is not an armchair theory, and in reality both businesses and workers are pursuing a work style that produces maximal profit every day. Therefore, there should be some people who will not fully understand what needs to happen when talking about work style reform.

But in economics, rational behavior is merely a basic principle, and there will always be exceptions. For example, there are many instances where corporate behavior and workers' behavior that used to be rational somehow turned out to be irrational as working environments changed. In the long term, such irrational behavior will be corrected over time, but in the meantime irrationality will be seen everywhere. In other words, whilst changes in the working environment are ongoing, rational behavior will not take place in the shorter term. Therefore, conversely, and quickly, picking up on these changes in the business environment to work on transforming behavior so that it becomes rational may potentially serve as a business opportunity. In fact, these circumstances fit the current Japanese work style. It can be said that because there is a problem with the work style, work style reform in Japan has become a business opportunity.

A typical Japanese work style employs new graduates all at once and trains them in-house over a long period of time, thereby aiming to achieve greater labor productivity and international competitiveness, and minimizing unemployment in the labor market. In the past, this custom has been highly acclaimed both domestically and internationally for its outstanding economic rationality. But with serious labor shortages becoming a reality due to the declining birth rate and aging society, and as competition continues to intensify due to globalization, the environment surrounding Japanese businesses is starting to change dramatically. Hence, unlike the past, it has become difficult to secure a talented workforce centering mainly on new graduate male workers, and greater utilization of women, midcareer hires, elderly workers, and foreign workers has come to be essential. In addition, diversification of value sets amongst the workforce has also progressed, and there has been more emphasis on work-life balance, not a work-centered life. During the high economic growth period where Japan needed to catch up with developed nations, volume input by workers with homogenous skill sets working for long hours produced mass added-value. But Japan has achieved economic growth and no longer needs to catch up, and rather is required to deliver high-quality creativity which can spark innovation of its own.

Under this new environment, the rationality of a traditional work style which is male oriented, working in the same company for long hours, and for a long time, has undoubtedly decreased. To back this observation, I conducted a series of empirical studies which covered the traditional work style, and it was shown that businesses that are planning to review the traditional work style and plan transformations achieve a higher performance. Below are some of the research findings on this point.

Work-life balance policies and corporate productivity

Since 2007, when the Work-Life Balance Charter and Action Guidelines for Promotion of Work-Life Balance were formulated, many Japanese businesses have introduced various work-life balance policies (WLB policies) to aim at a work style that allows employees to achieve work-life balance. But have performances improved at these businesses?

To grasp how work-life balance programs influence corporate performance, it is desirable to use panel data from longitudinal surveys of corporates for a certain period of time. Even if data for a given point in time show that businesses with WLB policies perform better, the reality often reflects the "reverse causality" where the larger and better businesses with good earnings are, the more capacity they have to implement WLB policies. Associate Professor Toshiyuki Matsuura of Keio University and I combined the micro data from the Basic Survey of Japanese Business Structure and Activities (Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry) with our own survey data, and compiled corporate panel data for 1,677 businesses over the last few decades, and verified quantitatively whether businesses that introduced WLB policies showed higher corporate earnings. By comparing earnings before and after the introduction of WLB policies, we were able to correctly grasp what positive impacts businesses were able to bring to earnings by introducing WLB policies. In addition, by focusing on Total Factor Productivity (TFP), an hourly productivity index which also takes into account the difference in labor hours to look at corporate earnings, the impact it has on mid- to long-term corporate growth capacities can be verified.

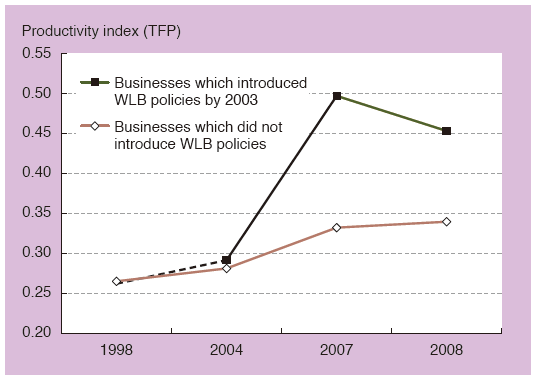

The analysis first showed that although there were cases of WLB policy introductions resulting in higher corporate productivity, for most of these instances the actual rise in productivity took a few years. For example, Chart 1 shows the trend in corporate productivity for businesses which introduced WLB programs such as establishing promotion organizations. There does not seem to be much difference in productivity growth with other businesses, but a sharp increase can be seen after a few years. In addition, a more detailed statistical analysis showed that while some cases see the effect coming in within one or two years, there have been many cases where the rise in productivity was seen after a mid- to long-term span of more than five or six years. This implies that while businesses need to be prepared to take on a rise in various short-term costs, productivity increase can eventually be expected with the introduction of WLB policies.

What types of WLB policies tend to result in a rise in corporate productivity? Effective WLB policies include various programs such as establishing a promotion structure, organizational programs to reduce long working hours, and a career transfer system from non-regular to regular employment status. In addition, the following corporate features saw a rise in productivity through introduction of WLB policies: mid- to large-sized businesses with more than 300 employees, manufacturing companies, businesses that have maintained their staff level and have kept the workforce during the recession period, and businesses with equal opportunity policies. To begin with, the channels through which WLB policies raise corporate productivity are pointed out to be improvements in hiring performance, improved retention rates of talented workers, and improvements in morale of employees. Thus, the effects of WLB policies are more visible at businesses that value their workers. In other words, at businesses where the model of corporate growth through human resources utilization can be applied, policies aimed at achieving work-life balance for its employees are not considered as costs but rather as investments. Therefore, businesses should proactively utilize WLB policies as part of their management strategy.

Promoting women's active participation and profit margins

Many businesses are currently contemplating, or have implemented, promotion of women's active participation. There are those businesses that aim to utilize as many talented workers as possible to survive fierce competition, and there are those that act out of social responsibility in response to the government or society. Then there are also those that promote women's active participation from a mid- to long-term perspective by preparing themselves for the coming shortage in labor expected with the super aging society. What effect does utilizing women have on Japanese businesses?

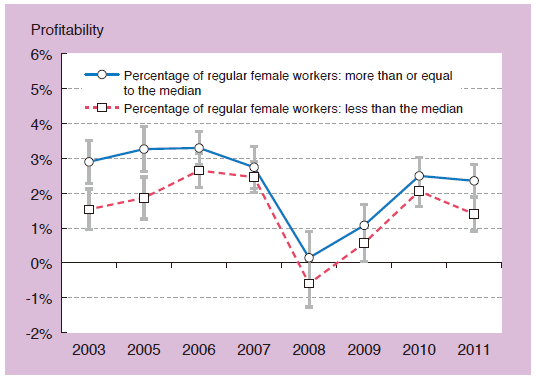

Looking at empirical studies using panel data of Japanese businesses, the more the businesses are involved in promoting women's active participation, the higher the corporate performance. For example, Chart 2 shows trends in the profit margins of publicly listed companies with a high percentage of regular female workers against those with a low percentage, and for all the years profit margins are higher for those companies that are advanced in utilizing female workers. This point is unchanged even when other factors such as industry sectors, business size, and sales size are statistically controlled, or when a reverse causality, such as if the company had room for promoting women's active participation because of its high profit margin to begin with, is statistically removed as much as possible.

What gives rise to such a relationship between active participation of women and corporate performance? In economics, there has long been a theory called the Taste-based Discrimination Hypothesis. Under this theory, if there has been discriminatory behavior and customs against women throughout the entire labor market, or if wages for women have been kept lower than their actual productivity, businesses that become forerunners in implementing programs to promote women's active participation are able to enjoy productivity higher than the wages, and therefore a rent-like excess profit is brought about to improve their corporate earnings. In other words, while paradoxical, if wages to productivity are at a discount for women compared to men, than the more the female workforce is utilized, the more businesses can save on labor costs, and thus improve corporate performance.

Unfortunately, the Japanese labor market looks to be just like this. As stated previously, there is a positive correlation between the percentage of fulltime female workers and profit margins. There is also a wage gap between men and women for all indices, and the Gender Gap Index of the World Economic Forum always places Japan towards the bottom. This situation needs to improve, but it may be useful for businesses to be mindful of the direct impact promoting women's active participation has on saving labor costs. For example, if the economic rationality of promotion of women's active participation can be lobbied to Japanese businesses, and if management can renew its perception that "if businesses change hiring policies for women and aggressively utilize them as fulltime workers, it would be effective in reducing labor costs and raise profit margins," then this new perception could also serve as the driving force for active participation of women in the workforce. Naturally, as utilization of female workers progresses in the overall labor market, wages for women will increase and the rent of labor costs will eventually disappear. In order to shorten this transition process, the labor-cost-saving aspect of the economic rationality of active participation of women should be emphasized as a policy choice.

In addition, promotion of women's active participation is not only effective in reducing labor costs, but also in raising productivity itself. The difference in productivity of male workers and female workers arises from various factors, such as characteristics of the assignment, attitude towards work, and the surrounding environment. For example, in manual labor which requires physical manpower, productivity of male workers will tend to be higher, but in areas like product design and development where women are the prime customers, productivity may be higher for female workers. Looking at Japanese businesses, there have been reports of the potential for a positive impact of the utilization of women on management in areas such as product innovation (developing products which have utilized women's perspective), process innovation (sales strategies which have utilized women's perspective), and improving the motivations of workers.

In other words, promotion of women's active participation not only saves labor costs as mentioned, but through utilization of the talents and skill sets of women, corporate performance can improve through enhanced productivity. Moreover, if promotion of women's active participation can improve productivity itself, then in addition to just raising the percentage of women in the workforce, an environment where women can fully demonstrate their abilities and skill sets can also be laid out, and further improvement in corporate performance can be expected as a result of the synergy effect.

In fact, according to my analysis using panel data of public-listed companies, businesses with many mid-career hires or proper work-life balance policies (child care and family care leave of absence systems which exceed the legally set standard, systems for shorter working hours, systems where an employee's work place is limited, programs to correct extended working hours, etc.) in place saw a significant positive impact on profit margins from the percentage of fulltime female workers than did other businesses. Businesses utilizing a number of mid-career employees or working to achieve work-life balance are open to recognizing diverse working styles and values, and therefore it can be interpreted that women are more able to demonstrate their abilities in such businesses, and hence their productivity is significantly enhanced.

Health management & profit margins

With the amendment to the Industrial Safety and Health Act, which enforced mandatory stress checks for employees, there has been a rise in social interest in mental health issues. The importance of "health management," which businesses implement as a management strategy to maintain and improve the health of their employees, has also been pointed out. On the back of these developments, Professor Sachiko Kuroda of Waseda University and I conducted a joint study to quantitatively verify the relationship between mental health and corporate earnings.

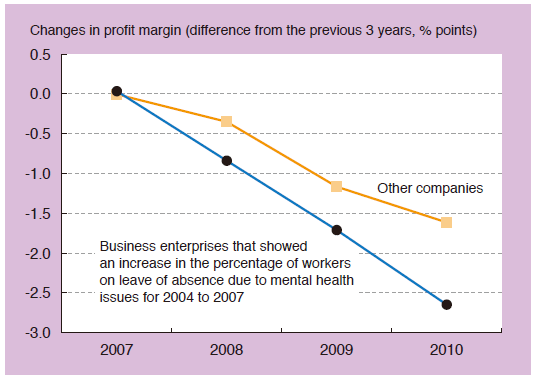

Chart 3 shows the trend in profit margins from 2007 to 2010 using panel data which tracked roughly 400 businesses. Chart 3 separates those that saw a rise in the percentage of fulltime regular workers on extended leave of more than one month consecutively due to mental health breakdowns (percentage of workers on mental health leave) for the period between 2004 and 2007, and those that did not. This allows comparisons between the trends in profit margins.

Chart 3 first shows that in 2007, there was no major change in profit margins between those businesses with a rise in the percentage of mental health leave workers and those with no change. But during the economic downturn period, between 2008 and 2010, caused by the financial crisis, all businesses saw a drop in profit margins, and the drop is larger for businesses which saw a deterioration in the mental health situation. In addition, when further analysis which took into account other factors more rigorously and statistically was conducted on the relationship between the percentage of workers on mental health leave and profit margins, it showed that with an increase of 0.1% in the percentage of workers on mental health leave, profit margins dropped by a significant 0.16% with a time lag of roughly two years.

The percentage of workers on mental health leave, which this study focused on, was on average around a mere 0.5%, and this number is small. Therefore, this may raise the question as to whether a very small percentage of workers taking leave of absence does in fact lower profit margins. Several interpretations apply to this point. First, corporate losses stemming from mental health issues are not limited to non-utilization of the workforce due to leave of absence, but it also lowers productivity during work hours, or lowers productivity due to leaving early, coming in late, or being absent from work. Therefore, this interpretation sees that the percentage of workers on mental health leave only captures one dimension of the mental health problems of employees. Further statistical analyses using the panel data of the employees actually confirmed that in a workplace where there are employees with mental health problems, the mental health of other employees also tended to deteriorate. Workers on leave due to mental health problems may just be the "tip of the iceberg" when the company or the workplace is regarded as one unit.

Another interpretation is that businesses and workplaces where workers take leave of absence due to mental health problems may be carrying some sort of issues in the workstyle and that this issue manifested itself in the increase in the percentage of workers on mental health leave. This point is also shown through the statistical analyses using panel data for employees, which highlight factors that negatively affect mental health such as long overtime hours without pay, unclear job descriptions, and a workplace culture which prevents employees from leaving work early. All these factors contribute to increasing inefficiencies in work style, and therefore it can be interpreted that work style lies at the root of mental health problems.

Thus, deterioration in the mental health problems of employees can lead to deterioration of corporate earnings. Businesses need to be mindful of this to address deterioration of mental health as a management challenge, and work to prevent it.

The three research findings above show that corporate programs such as introduction of WLB policies, promotion of women's active participation, and health management have great potential to improve corporate earnings. Rather than following the traditional Japanese employment custom, all findings show that reforming it to match the current era and environment raises economic rationality, and hence serves as scientific evidence pointing to the need for work style reform.

This article first appeared on the May/June 2017 issue of Japan SPOTLIGHT published by Japan Economic Foundation. Reproduced with permission.

May/June 2017 Japan SPOTLIGHT