The impact of artificial intelligence on office work and the impact of telework on offices are often examined separately. This column uses survey data from Japan to examine whether artificial intelligence and ‘remote intelligence’ are complements or substitutes. The authors find preliminary, albeit weak, evidence that that the two acting as complements in many office occupations.

Newsfeeds and economic journals are abuzz with two trends that are treated as separate but shouldn’t be.

- The first trend is the impact of artificial intelligence on office work (Brynjolfsson et al. 2023, Albanesi 2023).

Recent breakthroughs in generative AI, such as ChatGPT, are transforming many office and professional jobs. But even before ChatGPT, software such as robotic process automation (RPA), chatbots, and automatic translation apps were automating many tasks traditionally performed by office workers.

- The second strand is the impact of telework on offices (Barrero et al. 2023, Shah 2024).

This includes international remote work (Drenik 2022, Baldwin 2019).

If we label telework as RI, short for remote intelligence, then we can talk about the two trends as AI and RI. AI and RI affect the same jobs, and both are enabled by digital technology. As we are not talking about all of AI, we also call the applicable bit of AI ‘white-collar robots’ to distinguish them from industrial robots, or blue-collar robots, that work in factories.

Why are the two literatures so disconnected? It may be a fool’s errand to ponder why people haven’t thought of things, especially given that one of us wrote a whole book about the confluence several years ago (Baldwin 2019). But this disconnect is especially puzzling given how research was done during the economy’s previous close encounter with technology – specifically, information and communication technology (ICT). Feenstra and Hanson (2001), for example, sought to tease apart the wage inequality impact of ICT (skill-biased technology) and increased competition from globalisation (offshoring).

There is a very practical, and we think important, question that has been left aside by the silo-isation of the AI and RI literatures.

Are AI and RI complements or substitutes?

To address this question, we undertook a large survey on AI and RI in Japan. We collected a several waves of surveys of about 10,000 workers, with the first wave starting – fortuitously – right before COVID-19 hit Japan and continuing until late 2022.

The fact that we have data before during and after COVID restrictions provides an exogenous shock that allows us to tease out the AI-RI links. In Baldwin and Okubo (2023), we attempt to empirically investigate whether AI and RI are complements or substitutes in the service sector. To presage our results, we find preliminary evidence that suggests that AI and RI are complements rather than substitutes.

In this column, we first graphically set out the question with what we call the globotics diagram. And then we turn to considering unconditional correlations in our data. The evidence comes first from the positive correlation of investments in AI-promoting and RI-promoting software at the firm and worker level, and second from the positive correlation of workers' expectations regarding telework and software automation. The evidence is far from definitive but suggests that the complement-substitution question is a fruitful line for future research.

Teleworkability and automatability in the US and Japan: The globotics quadrant diagram

Some jobs require people to work together in the same place and so are not teleworkable, while other jobs cannot be replaced by white-collar robots and so are not automatable. For occupations, where both automation and telework are feasible, the complements/substitutes question is a live one. So, how many occupations fit this prerequisite?

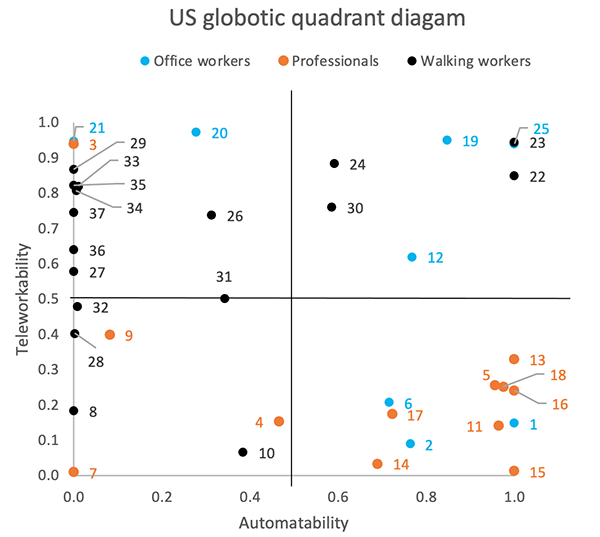

We plot the teleworkability and automatability of each occupation is a scatter plot that we call the globotics quadrant (Figure 1). We use Dingle and Neiman (2020) for the teleworkability vertical scale, and Frey and Osborne (2013) for the automatability scale. The horizontal and vertical lines are drawn at the mean value for all occupations, so automatability of the occupations to the left of the vertical line is below average, and teleworkability of those below the horizontal line is below average. Here we present the globotics quadrant for the US; see our paper for what the diagram looks like for Japanese occupations.

Note: Each point represents an occupation; x-axis shows the automatability score (from 0 to 1), and y-axis is teleworkable Score (0 to 1). Occupations grouped into Japan’s NIRA38 aggregates. The point labels refer to the Japanese occupation categories.

The key takeaways from the globotics diagram are simple.

- First, occupations are spread across all four quadrants, so the impact of advancing digital technology will vary greatly by occupation.

There can be no universal answer to the question of whether AI and RI are complements or substitutes.

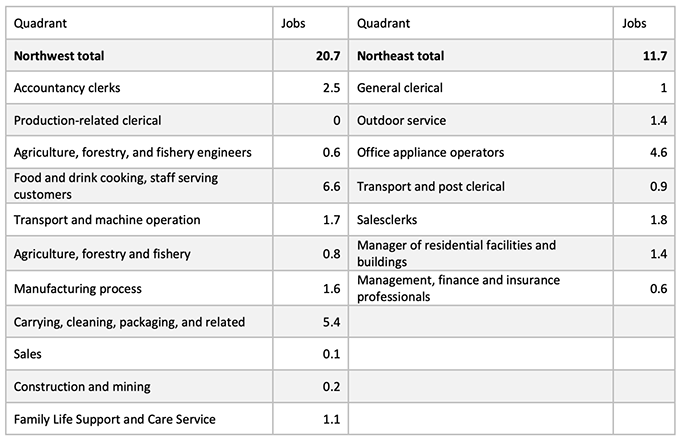

- Second, there are about 12 million workers in the occupations found in the top-right quadrant, which is about 10% of the occupations classified (see Table 1 in the Annex).

- Third, there is no clear correlation between teleworkability and automatability.

These unconditional facts stress the need for nuanced thinking.

Motivating facts

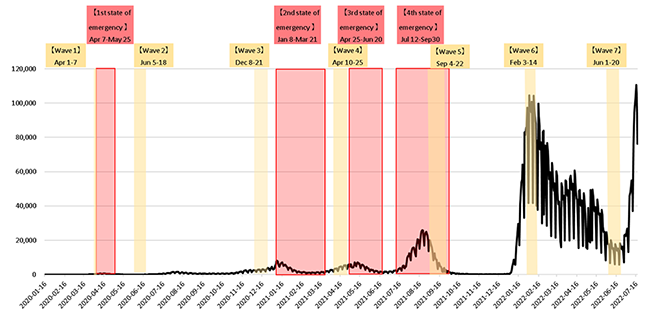

We now turn to our survey data (Okubo and NIRA various, Okubo 2022). These come from comprehensive surveys of around 10,000 workers (in a randomly stratified sample) that were undertaken in Japan in seven waves. Figure 2 shows the daily number of new cases of COVID-19 in Japan, including the dates of government-declared states of emergency as well as the timing of the various waves of the Okubo-NIRA surveys (Okubo 2022).

[Click to enlarge]

[Click to enlarge]

Evidence from software investments: Main results

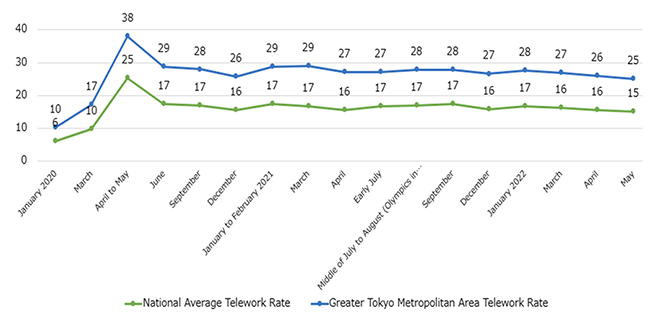

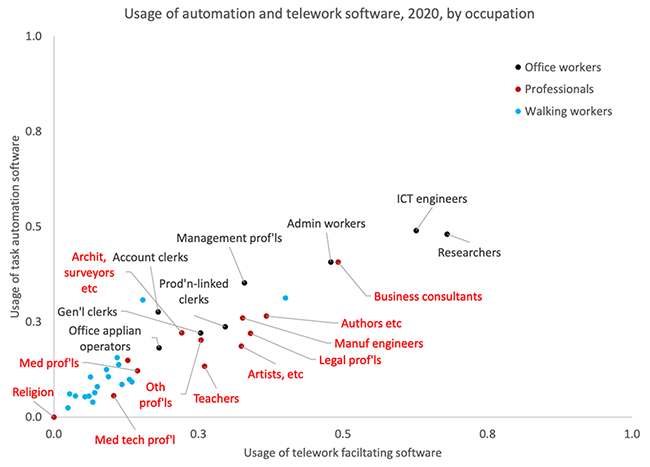

To reduce the dimensionality of the many questions asked, we aggregated the responses into two indices: pro-AI and pro-RI (see our paper for details). The results are shown, by occupation, in Figure 5.

The occupations are segmented into three broad categories (office workers, professionals, and walking workers). The chart shows a clear and strong positive correlation between the level of usage of both types of software across occupations. In certain occupations, especially those in the office and professional categories, the respondents were already widely exposed to AI-promoting and RI-promoting software. The top users are ICT engineers and research. Many other occupations, especially those in the walking workers category, did not use much of either type of software.

[Click to enlarge]

Note: the indices are coded to be 1 or 0 at the respondent level and then averaged over workers with that occupation in all industries.

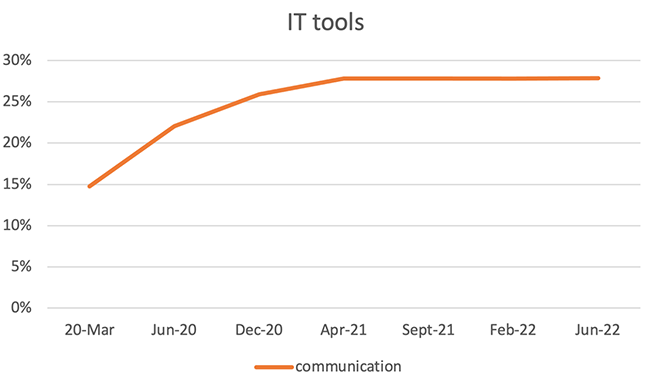

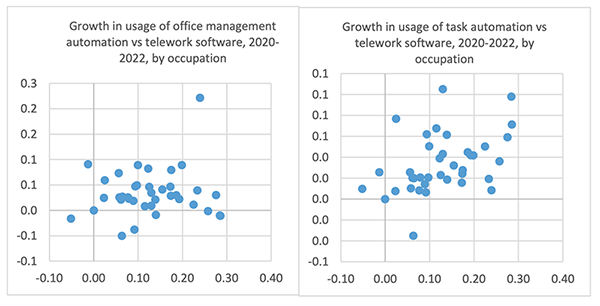

To further investigate this negative correlation, we divided the overall office automation index into two subcomponents: direct service task automation software (such as robotic process automation) and automation of office management systems (which are often related to handling information concerning workers in the office; see function categories of Table 2). The findings are displayed in Figure 6.

[Click to enlarge]

Note: Growth in pro-teleworking software usage is on x-axis of both charts; the y-axis for the left chart is the change in usage of office management software while the y-axis of the right chart shows changes in usage of repetitive service task automation like RPA

In both panels, the figure plots the horizontal axis is the change in usage of software that promotes telework (pro-telework software such as Zoom, Slack, cloud-based file sharing, etc.). The left panel shows the automation software related to managing workers (management automation software) (e.g., HR management tools).

Thus, there is weak evidence for substitution of AI and RI for software which automates some management tasks related to workers. Further research would be needed to establish causality, but the charts are certainly in line with the notation that less management-facilitating software is needed when there are fewer workers in the office.

The left panel of the data shows a mild negative correlation, or no correlation at all, between the usage of task automation software and pro-telework software that supports remote work. This is not unexpected since the need to expand the usage of management software might not be augmented as the share of workers actually in the office falls. The facts on office management automation and telework-facilitating software suggest that, at the occupation level, firms do more of both at the same time.

Evidence from workers’ expectations

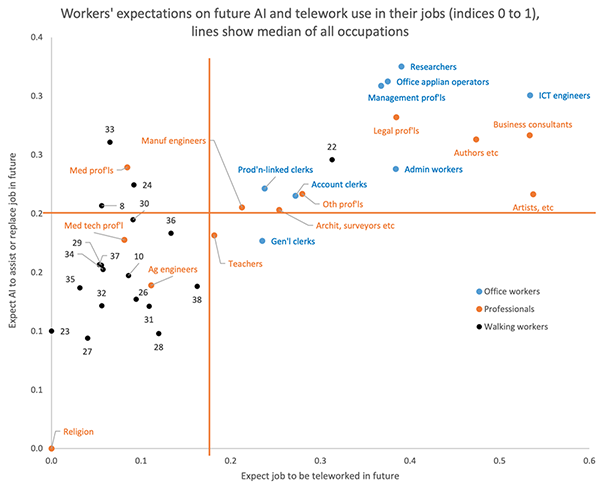

The final strand of evidence comes from a unique set of questions, which included the fifth wave of the survey that asked workers about their expectations about the future of their jobs. Will your work be assisted by automation technology such as AI and robots in the future? Will your work be replaced by automation technology such as AI and robots in the future?

This evidence (Figure 7) needs careful handling since the answers are from workers who have jobs. One scenario that could be consistent with an AI-RI substitutes hypothesis is that the workers who retain their jobs will be both teleworking more and using more AI, but the number of workers falls as AI raises the productivity of the remaining workers. But at least at the level of occupations, the chart provides clear evidence that the occupations that are the most teleworkable are also those that are most susceptible to automation.

[Click to enlarge]

Note: the indices are coded to be 1 or 0 at the respondent level and then averaged over workers with that occupation in all industries. Ag workers, 33; Carrying, cleaning etc, 37; Construction workers, 36; Food services, 29; Buildings managers, 30; Manuf workers, 34; Occ'l health workers, 28; Other, 38; Other service workers, 31; Outdoor serv workers, 23; Social work prof'l, 10; Nurses etc, 8; Sales clerks, 22; Sales workers, 26; Security workers, 32; Transport workers, 35; Transport workers, 24; Family care workers, 27

Summary and concluding remarks

Our paper provides weak, preliminary evidence at the occupation and worker level that AI and RI are acting as complements in many office occupations in Japan. Forms are AI-linked software that directly replace repetitive information processing services tasks are positively correlated with investment in telework-facilitating software. This suggests that this type of AI is complementary with RI. For other forms of automation software, there is some weak evidence of substitution.

More careful econometric work is needed to move beyond our exploration of the unconditional facts, but we can already speculate about policy implications. One concerns that trend toward international offshoring of office jobs, i.e. international telework, or telemigration. GenAI is replacing some of these foreign workers (e.g. low-end call centre workers replaced with chatbots), but at the same time offshore workers with excellent GenAI tools can provide better service. Thus, the arrival of ChatGPT may not threaten the trend towards service-led development that relies on back-office offshoring.

Annex

Note: Each point represents an occupation; x-axis shows the automatability score (from 0 to 1), and y-axis is teleworkable Score (0 to 1).

This article first appeared on VoxEU on March 26, 2024. Reproduced with permission.