Communication strategies are increasingly seen as an important tool for central bankers to guide expectations. This column applies statistical natural language processing algorithms to press conferences given by two different governors of the Bank of Japan during a time without any formal changes in institutional arrangements for communication policy at the Bank. Communication strategies are found to differ vastly across the two governors, with one governor focusing on the topic of ‘discretion’ and the other on the topic of ‘policy goals’.

The idea that communication strategies are a policy tool for central bankers in advanced economies continues to gain influence and momentum. At the Jackson Hole Conference in 2019, the Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell shed light on the role of communication in what he called "the new normal," where he said "we face heightened risks of lengthy, difficult-to-escape periods in which our policy interest rate is pinned near zero," for which "we are conducting a public review of our monetary policy strategy, tools, and communications---the first of its kind for the Federal Reserve. … In addition, we are looking at how we might improve the communication of our policy framework." (Powell 2019, emphases added). During the secular stagnation that occurred in the course of the Great Recession, the US FRB struggled with the meagre efficacy of unconventional monetary measures including forward guidance, especially once nominal interest rates faced a zero lower bound. The ‘new normal’ now requires central bankers, including Chairman Powell, to reflect on the type of central bank communication that is most complementary to the renewed policy framework.

History repeats itself. In the 1970s, the US economy was confronted with stagflation, and pessimism about anti-inflationary monetary policy in response to economic slack was prevalent with both FRB Chairmen William Miller and Arthur Burns in office. Their discretionary attitude towards controlling inflation resulted in inflationary expectations by the public which, in turn, caused the period known as the Great Inflation. Inflation was then combatted by a rule-based policy of controlling non-borrowed reserves, progressively initiated by Chairman Paul Volker in 1979. The debate over rules versus discretion in monetary policy swept the macroeconomic literature, led by a game-theoretic model by Barro and Gordon (1983) which shows that in order to attain a social optimum, governments can credibly commit to forgoing inflation bias. However, it is more favourable for governments to maintain flexibility in the event of exogenous supply shocks that affect output. The trade-off for central banks between credibility and flexibility provides a rationale for utilizing ambiguity in revealing their private information, a practice which was labelled ‘monetary mystique’ by Goodfriend (1986).

This old view of central bank communication based on the time-inconsistency problem might have been indicative of how credibly or flexibly central banks act when they reveal private information to rationally attentive agents with expectations biased towards being inflationary. However, the current economic situation is the opposite of the economy in the 1970s, as expectations of otherwise inattentive agents are stimulated by high pressure from the central bank. Among the unconventional policy remedies against secular stagnation, forward guidance with overshooting quantitative easing (QE) continuation was intended to prevent time inconsistency from weakening the increase in inflationary expectations. However, forward guidance unexpectedly failed – which poses another puzzle for macroeconomists to solve (Campbell et al, 2012).

Nakamura and Steinsson (2018) highlight the ‘information effect’ of monetary policy announcements, including forward guidance. If private agents are uncertain about the natural rate of interest in an environment where it is believed to be a sufficient statistic representing the state of the economy, a policy change itself reveals news of such fundamentals to those private agents. The common understanding among market participants is that the central bank's announcement of further easing is intended to stimulate the economy -- an ‘Odyssean’ commitment according to Campbell et al. (2012). However, such a policy change might also be taken as an indication that the central bank has worse news on macroeconomic fundamentals, and hence result in so called ‘Delphic’ pessimism among market participants.

Is there any mechanism of central bank communication which could prevent the Delphic information effects, but is still consistent with monetary policy action supported by a theoretical foundation? In Keida and Takeda (2017) and Keida and Takeda (2019) we address this question by taking a natural language processing approach studying the regular press conferences held by two governors of the Bank of Japan (BOJ), following the narrative economics of Shiller (2017) and Shiller (2019) (Note 1).

Shiller (2017) proposes that "the field of economics should be expanded to include serious quantitative study of changing popular narratives. To my knowledge, there has been no controlled experiment to prove the importance of changing narratives in causing economic fluctuations." Romer and Romer (2013) share the same spirit as Shiller, presenting narrative evidence for the US of a link between pessimistic beliefs in the efficacy of monetary policy and the policy inaction among monetary policymakers, not only during the 1930s after the Great Depression but also during the stagflation in the 1970s and after the Great Recession in 2008. During these critical moments, the pessimism of central bankers was publicly revealed and caused the public to lose faith in monetary policy as an effective panacea for remedying economic crises.

In Keida and Takeda (2017) and Keida and Takeda (2019) we exploit a significant difference in the communication strategy by two governors of the Japanese national bank to study the effects of changing narratives on economic fluctuations. This controlled experiment allows us to single out the effect of communication strategies as there were no obvious formal changes in institutional arrangements for communication policy during the time of study. We analyse the narrative in regular press conferences (held and recorded in Japanese after each Monetary Policy Committee meeting) used by governor Masaaki Shirakawa (in office 2008-2013) and governor Haruhiko Kuroda (in office 2013-present). There are significant differences in the communication strategies of these two governors. Governor Shirakawa made constant use of highly technical and academic language and openly exposed his pessimism about the central banks' ability to raise inflation levels. Governor Kuroda, on the other hand, delivered prepared statements that only highlighted the positive effects of on-going policy, seemingly believing Peter Pan, who said "the moment you doubt whether you can fly, you cease forever to be able to do it." This setting should therefore be appropriate for studying the extent of the ‘Delphic’ information effect of the unconventional monetary policy measures the BOJ has continued to pursue over the span of the two governorships.

To extract semantic information relative to numerical information from the BOJ governors' regular press conferences, we rely on statistical natural language processing, where each word is assumed to be chosen from ‘a bag of words’ following a document generation process (Note 2). In Keida and Takeda (2017), we apply latent semantic analysis (LSA) to detect similarities/dissimilarities between the two governors' wordings. The LSA finds completely different wordings used between Shirakawa and Kuroda, as well as a drastic change of wordings during the governorship of Kuroda in early 2016 when the negative interest rate policy was introduced. However, the analysis provides no information on what caused the changes in content.

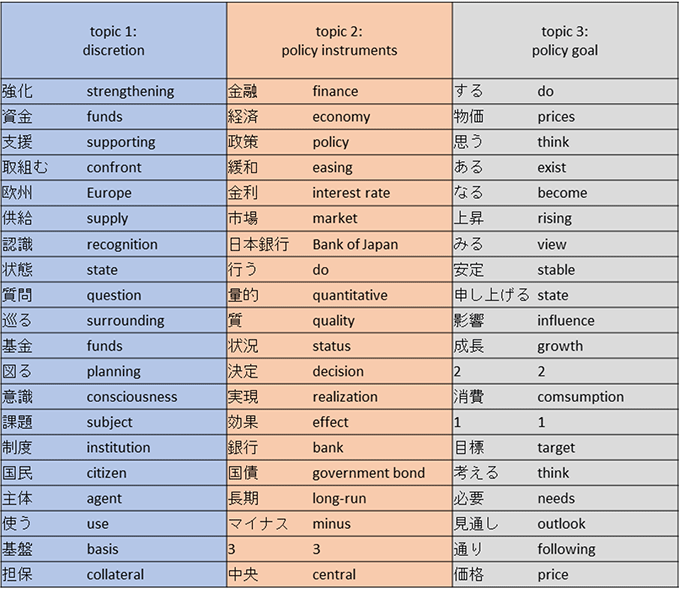

In Keida and Takeda (2019), we estimate a topic model applying another method for statistical natural language processing, the latent Dirichlet allocation (LDA). The LDA assumes that topics follow a Dirichlet distribution of words contained in documents, each of which has several topics as another Dirichlet distribution.

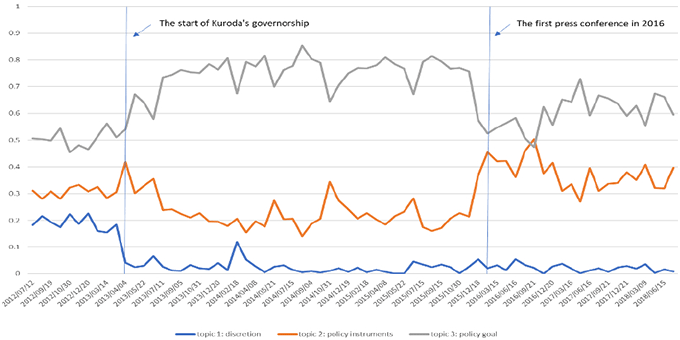

We again focus on detecting changes in the communication strategies of the two BOJ governors by analysing the 10 regular press conferences held by governor Shirakawa and the 60 regular press conferences held by governor Kuroda from July 2012 to July 2018.

Our estimation results and some interpretations are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1. In the old view of central bank communication based on rules versus discretion in monetary policy, Kuroda's explicit rule policy may be seen as lowering the importance of the ‘discretion’ topic. After losing credibility in achieving his goals in 2016, his statements increasingly contained references to the topic of ‘policy instruments’. In the view of flexibility versus credibility in monetary policy, the topic of ‘discretion’ is interpreted as being effective in increasing flexibility and lowering credibility. Alternatively, it is possible that the communication strategy during the tenure of governor Shirakawa was Delphic (Campbell et al. 2012) in that announcements of unconventional measures revealed bad news on economic fundamentals.

What lessons should we learn from the contrast in communication strategies between the two central bankers? In particular, how could central bankers prevent the Delphic information effects associated with making monetary policy decisions? Are there any theoretical frameworks for the art of central bank communication? For the sake of answering these questions, we are in the process of constructing a cheap-talk game model for an economic environment with politicians and investors with heterogeneous preferences for unanticipated inflation caused by monetary policy-decisions.

This article first appeared on www.VoxEU.org on April 17, 2020. Reproduced with permission.