Small and medium-sized firms can enjoy the benefits of trade liberalisation by exporting their goods or importing inputs through intermediaries. Using firm-level data from Japan, this column finds that firms in regional areas are smaller than those in metropolitan areas and are less likely to participate in indirect or direct trade. Direct and indirect exports and imports represent a large share of regional economies, and indirect exporters in regional areas are likely to become direct exporters. In addition, both newly started direct export/import firms and newly started indirect export/import firms tend to grow faster.

The international trade literature has investigated the merits of trade since Ricardo (1817). A recent development, the heterogeneous firms trade model pioneered by Melitz (2003) and Eaton and Kortum (2002), shows that for domestic firms, trade liberalisation favours only the most productive firms because it allows them to enter foreign markets. In contrast, the least productive firms are forced to exit the market because of tough competition from more foreign competitors. However, there are firms in the middle of these two groups of firms, which benefit from indirectly participating in global value chains by exporting their goods or importing inputs through wholesalers or other manufacturing firms.

As Bernard et al. (2010), Ahn et al. (2011), Crozet et al. (2013) and Akerman (2016) and others argue, although some firms are not sufficiently productive to serve foreign markets, they can export their products through intermediaries, which reduces export-related fixed costs by spreading them among many export clients. Thus, many small and medium-sized firms can enjoy the benefits of trade. Firms in more rural regional economies, especially, are smaller and less productive and thus less likely to directly export their goods.

Using firm transaction data of Japanese firms, in a recent paper (Ito and Saito 2018) we attempt to establish stylised facts on direct and indirect trade and its impact on firm performance, with the special goal of shedding light on the characteristics of more rural regions and indirect exports/imports. (Note 1)

Data and methodology

We use firm-level transaction data for firms compiled by Tokyo Shoko Research Limited, a private company, which records data on both listed and non-listed companies in Japan. The main information included in the dataset are transaction data for both sales and purchases between firms and several facts about each firm, including the year of establishment, paid-up capital, total sales value and number of employees. The dataset covers approximately 1.4 million firms and about 8 million transactions between them for each year. The data are annual and covers 2012 to 2016. For each firm, a maximum of 24 transactions are recorded. It is highly probable that some firms have more than 24 transaction partners. We capture those cases by combining the reporters' transaction reports with those of the partners'. For example, those firms that are reported as partner firms by many reporting firms, such as Toyota, have more than 24 transactions.

The Tokyo Shoko Research data include information on exports and imports in addition to the firm-to-firm transaction data. When a firm indicates its status as an exporting (or importing) company, we designate the firm as having direct exports (imports). When a manufacturing firm's answer is "no exports (imports)" but it sells products to wholesalers that have export (import) status, we define the firm as having indirect exports (imports) through wholesalers. When a manufacturer's answer is "no exports (imports)" but the manufacturer sells its products to other manufacturers that have export (import) status, we define it as having indirect exports (imports) through other manufacturers. In short, export (import) status is classified into the following four types:

A) direct exports

B) indirect exports through wholesalers

C) indirect exports through other manufacturers

D) domestic transactions only

These categories are mutually exclusive, i.e. each firm is classified into only one of the above categories. Admittedly, this is not a perfect definition of indirect exports; it overestimates the true number of indirect exports in which wholesalers and/or other manufacturers only act as intermediaries. However, given the available information, this is the best solution and it is a method used by other researchers.

Out of approximately 140,000 manufacturing firms, for exports, 4.8% of firms are classified as type A, 14.6% as type B, 24.4% as type C and 56.1% as type D. For imports, the shares are 5.7%, 22.3%, 10.3%, and 613 %, respectively. The proportion of indirect exporters is much higher than that of direct exporters. The indirect exports through other manufacturers are larger than the indirect exports through wholesalers, whereas the opposite is the case for imports.

Main findings

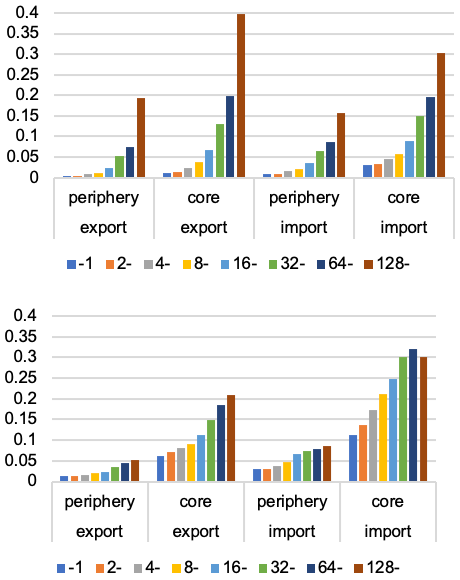

- The size of firms, in terms of the number of employees and sales values, is smaller in more rural regions than in major metropolitan areas. The case for the number of employees is shown in Figure 1. Interestingly, in the case of wholesale (bottom panel), the smallest firms in major metropolitan areas (‘core’) are more likely to be exporters than the largest firms in more rural regions (‘periphery’). Econometric analyses show that, even after controlling for firm size, firms in more rural regions are less likely to export, which indicates higher trade costs in rural regional economies. This is probably due to those economies having less information on overseas markets and lacking sufficient infrastructures for export activities.

Note: ‘Core’ represents major metropolitan areas, whereas ‘periphery’ represents other areas.

- Approximately 40% of firms in more rural regions are engaged in either direct or indirect exports and/or direct or indirect imports. This share in terms of the number of employees, sales values, and value-added in the more rural regions is close to 70%.

- Econometric analyses show that indirect exporters are likely to become direct exporters in more rural regions, which suggests that these firms actively engage in learning export procedures, customer search methods and information on foreign markets, whereas this is not found for the case of indirect importers.

- Econometric analyses show that both newly starting direct export/import firms and newly starting indirect export/import firms tend to exhibit the fastest growth. The size of this effect is larger for direct exporters/importers than indirect ones and the magnitude is larger for firms in more rural regions than for those in metropolitan areas.

This article first appeared on www.VoxEU.org on April 16, 2019. Reproduced with permission.