Occupational licensing is a common solution to the information asymmetry that exists in many professions and services. Using original survey data from Japan, this column examines how occupational licensing affects labour participation and wages. A majority of respondents are found to possess occupational licenses, and licensing is positively associated with labour force participation, particularly amongst women and the elderly.

Occupational licenses—such as those obtained by physicians, lawyers, accountants, schoolteachers, nursery schoolteachers, barbers, hairdressers, and massage therapists—are prevalent. In the US, for example, 35% of employees were either licensed or certified by the government, and 29% were licensed (Kleiner and Krueger 2013). In Japan, as part of regulatory reform, deregulation of the occupational licensing system has been discussed repeatedly since the 1980s. However, the pace of regulatory reform has been slow.

Benefits and costs of occupational licensing

The main purpose of occupational licensing is to protect consumers from the information asymmetry which is inherent in these professions (LeLand 1979, Shapiro 1986). In the service sector, where information asymmetry between service providers and users is often serious, a large number of occupations are regulated by a licensing system.

Occupational licenses have potential benefits as well as costs. The benefits include preventing the entry of low-quality providers, enhancing human capital investments, and improving the average quality of services. On the other hand, licenses may create monopolistic rents through their effects to restrict competition among actual and potential suppliers. In particular, the monopolistic licensing system, which has a strong entry deterrence effect, may have negative effects on market efficiency and productivity improvements. In fact, several studies detect wage premiums associated with an occupational licensing system (e.g. Kleiner and Krueger 2013, Kawaguchi et al. 2014, Gittleman and Kleiner 2016).

Occupational licenses are also related to the issues of female and elderly labour participation. If licenses function as a signal of specific skills, they may contribute to better matching of potential workers and actual jobs. In particular, females or elderly people holding restrictive licenses may find it easier to get new jobs after child rearing or compulsory retirement, respectively. In fact, a study in the US indicates that occupational licensing laws helped females and black workers, particularly in occupations for which information about worker quality was difficult to ascertain (Law and Marks 2009). If such functions operate effectively, the occupational licensing system may contribute to partially offsetting the negative impacts of the declining working age population.

A survey on occupational licenses in Japan

Although there is substantial research on specific licenses, such as those of physicians, dentists, lawyers, barbers, hairdressers, and massage therapists (see Kleiner 2000, 2006 for surveys), it is not easy to comprehend the actual situation and the economic effects of occupational licenses entirely, because possession and use of occupational licenses are generally not surveyed by official statistics.

Considering this background, I conducted an original survey of individuals to present new evidence on occupational licenses in Japan (Morikawa 2017). Specifically, I conducted the Survey of Life and Consumption under the Changing Economic Structure and Policies to collect information about occupational licenses as well as various individual characteristics. The main survey items used in the analysis are the possession and use of occupational licenses. The first question relates to the broadly defined license, including both monopolistic licenses and certifications. The second question relates to monopolistic licenses, which are treated as licenses in an occupation without which the worker would be prohibited from taking a job, based on the government's laws and regulations.

Using the survey data, I studied the individual characteristics of license holders, distribution of licenses by industry and occupation, the relationship between possession of licenses and labour market attachment, and wage premiums arising from possession/use of occupational licenses.

Occupational licenses and labour market outcomes

According to the analysis:

The majority (about 56%) of the respondents possess occupational licenses (including certifications) and about 40% of the working population use occupational licenses in their current jobs. In particular, the figures are higher in the service sector, where more than 70% of the workforce in the health and welfare, education, transportation, and finance industries possess licenses. Generally, attaining higher education has a positive association with possession of licenses, and those who graduate from professional schools tend to possess and use occupational licenses.

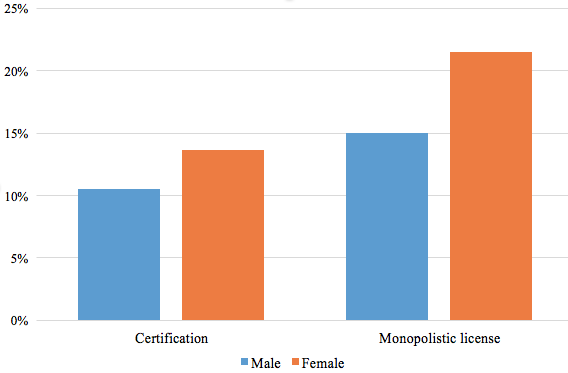

Occupational licenses have a strong association with the labour participation rate, particularly among females of all age classes and males in their 60s or over. The association with the labour participation rate is stronger for monopolistic licenses than certifications (Figure 1). Although these cross-sectional associations cannot be interpreted as causality, the result suggests that holding a monopolistic license has favourable effects on labour participation of females after child rearing, and of elderly people after compulsory retirement.

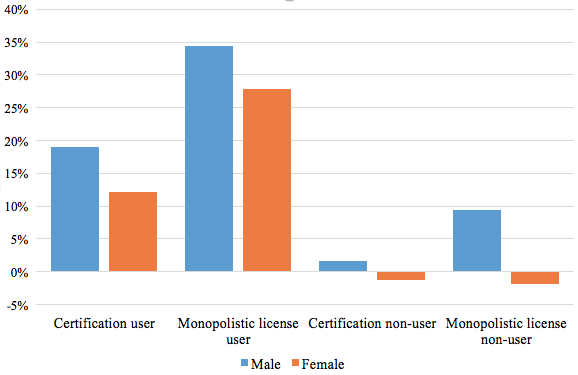

Although occupational licenses are associated with higher earnings, the prerequisite for a wage premium is the actual use of a license in a job (Figure 2). In other words, occupational licenses do not simply function as a signal of workers' potential ability, they are also important in improving the matching of specialised skills and actual jobs. The estimated wage premiums are greater for monopolistic licenses than for certifications, suggesting that monopoly rents are contained in wage premiums of some strictly regulated professions.

Overall, occupational licenses have a beneficial impact on the labour market outcomes of individuals, but may cause inefficiency in goods and service markets. Considering the important role of occupational licenses in the service economy, as Kleiner and Krueger (2013) suggest for the US, periodically collecting information in official statistics on the possession and use of occupational licenses will be very useful for future research.

Editor's Note: The main research on which this column is based first appeared as a Discussion Paper of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) of Japan.

This article first appeared on www.VoxEU.org on July 3, 2017. Reproduced with permission.