A major feature of globalisation in the last decades has been the emergence of global supply chains, especially in Asia. This column explains how supply chains may increase the risks of shock contagion across countries. It shows how the earthquake and tsunami in Japan, and the floods in Thailand had ripple effects on the Japanese automobile industry across countries. It suggests that greater international cooperation, such as the development of sister industrial clusters, is one way to mitigate the risks.

The Great East Japan earthquake which occurred on 11 March 2011 had a surpassing 20 meters high that hit several hundred kilometres of the Tohoku coastline on the eastern side of Japan, and cost the lives of approximately 18,000 people. This was followed by a nuclear crisis categorised as level 7 on the International Nuclear Event Scale. A nationwide electricity shortage ensued and the economic and infrastructure damage was about $200 billion.

The earthquake demonstrated the vulnerability of global supply chains to isolated events. The major disaster areas in Tohoku were Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima prefectures. Although their share of exports is just 1%, the initial damage in the areas largely impacted the supply chain throughout Japan, parts of East Asia, affecting major industrial agglomerations including those in Manila and Shanghai, and the rest of the world. The effect may have been stronger than expected (e.g. Escaith et al. 2011). The automobile industry, which creates its products by assembling 20,000-30,000 parts - including materials, electronics, and machinery - was the most affected sector, and it is unsurprising that it is vulnerable to supply chain disruptions.

Factory Asia

East Asia today is called the world's production centre based on this supply chain network. Why is there so much agglomeration of production throughout Asia? Key factors for agglomeration are scale economies and low transport costs.

- Lower transport costs encourage more concentration of production activity at a limited number of locations. For example, looking specifically at the automobile industry, a typical car is assembled from 20,000-30,000 parts. Each key part is usually produced at either one or a few locations, thus, all 20,000-30,000 parts are exchanged through a complex supply chain network that handles everything from the procurement of parts to the delivery of finished products.

- Moreover, in order to minimise inventory stock, each production centre adopts a just-in-time procurement policy. This is very efficient under normal conditions but is vulnerable to major disasters.

The effect of the disasters on the Japanese automobile industry

Roughly ten million cars are produced in Japan per year, with half of those sold domestically. Japanese automakers produce 13 million cars annually overseas, which requires key parts made in Japan as well. In the Tohoku region, factories in the northeast suffered from the tsunami, and the central region's factories, as well as the highways of the south, were affected by the Great East Japan earthquake. Some plants took more than a year and a half to recover, while others did not sustain any serious losses, but were unable to continue operations because of a lack of procuring parts from elsewhere.

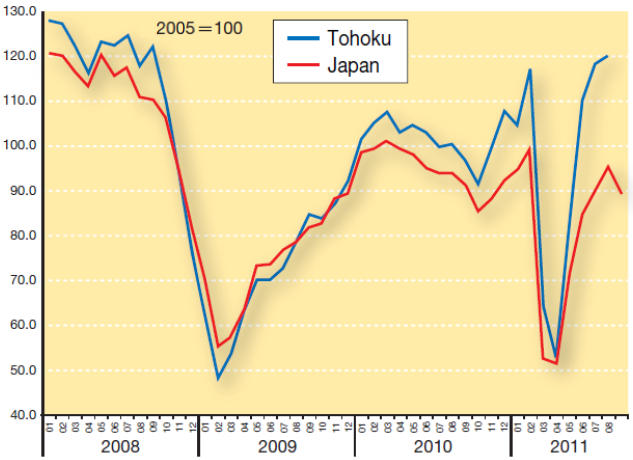

Looking at the automobile production index from 2008 to 2011, it appears that the Great East Japan earthquake and the Lehman Brothers collapse affected Japan's automobile industry equally (Figure 1). Both led to a 50% drop in monthly production. The automobile production trend in Tohoku is synchronised to the overall trend of automobile production in Japan. Although only the Tohoku region was directly damaged, the total Japanese automobile production rate fell by 50% because of supply change disruptions.

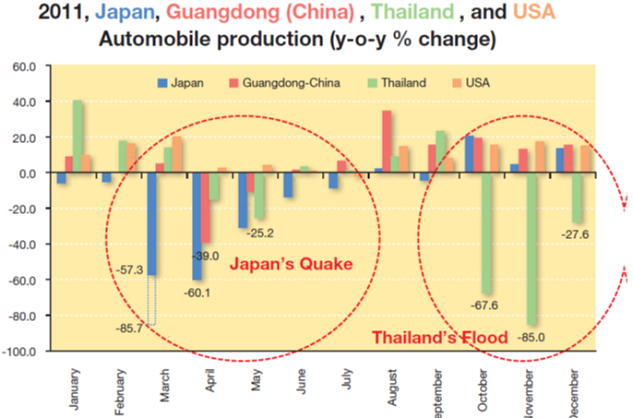

Shifting to Thailand, great floods occurred in September 2011. The Bangkok region is one of the biggest agglomerations of automobile and electronics manufacturing in the region. Most large Japanese electronic and automobile companies operate plants in the area and are supported by other plants that produce the most important parts. There are more than 1,300 Japanese firms in the area. Automobile production in Thailand in May 2011 was down by 25% because of a shortage of parts from Japan. It slowly recovered up until September, but then dropped sharply by 85% in November because of the floods (Figure 2).

Global impact

We can understand the global impact of the Great East Japan earthquake and Thailand's floods by looking at production data from Japan, the Guangdong region in China, Thailand, and the US (Figure 2). Up until 11 March 2011, Japan's production grew normally. After the earthquake, the automobile production in Japan fell to 85.7% in March. Production recovered gradually but decreased suddenly in September due to the floods in Thailand. Looking at statistics from Guangdong, production in April was down by 39%, and it recovered in August but dropped significantly in September again because of the floods. Looking at the US, the Great East Japan earthquake caused the production rate to drop, with the biggest drop in July, when the growth rate turned negative. The impact of the floods in Thailand was less significant for the US. The biggest drop in the production rate in Japan was in March, and in China, it was in April. In Thailand, this was seen a month later, in May, and in the US, it was in July. The greater the distance from Japan, the longer it took for the disaster to affect the country in question. This is likely because the further the distance of the production centre, the more inventory stock held. The quake and floods affected other Asian countries, specifically Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines.

This does not only affect the automobile industry. For instance, the price of a hard disk drive tripled following the floods as Thailand produces about 45% of the world's hard disk drives.

How can we enhance the resiliency of the global supply chains?

We must first recognise that no place in the world is risk free. There is the potential that supply chains may be disrupted due to a major disaster, including human-induced ones, such as conflicts.

In order to enhance the resiliency of the global supply chain, we must disperse risk. Automobile production tends to utilise tens of thousands of small companies that support major production networks. Because small companies are vulnerable to major disasters, group-wide cooperation is indispensable. There are many ways in which individual enterprises can enhance risk management, such as through the virtual and actual dispersion of key plants, standardisation of parts and materials, diversification of supplies, and utilisation of disaster insurance.

A concrete example of supply chain risk mitigation is a proposal from the Thai government to develop sister industrial clusters. According to this proposal during normal times each production cluster will focus on its own special products. However, in the case of a major disaster, the region's sister cluster would step in to provide backup production of common parts. Such country-to-country cooperation is very important. While we compete with each other during normal times, we should cooperate in times of disasters.

International cooperation is essential to the enhancement of resiliency in developing countries. Particularly in developing countries regional cooperation, including regional or national government infrastructure improvements, is essential. Of utmost importance for these countries is to prevent urban flooding and ensure a stable electric supply. We need more resilient and nationwide systems. During the 1950s and 1960s, major typhoons greatly impacted production systems in Japan. Japan subsequently developed infrastructure, such as water systems and electrical systems, to address this, thanks to assistance received from the World Bank and the IMF, among others. This same process should be carried out in major developing countries throughout the world.

International cooperation is essential, as is cooperation on innovation toward upgrading our brainpower networks. The lessons of Japan and Thailand are that we should work to move the supply chain toward greater safety.

This article first appeared on www.VoxEU.org on November 18, 2013. Reproduced with permission.