In Japan, hot springs and health have long been closely associated. Before the establishment of modern medicine, there were hot spring healing methods that included bathing in them or drinking from them, and in the Edo period it became popular to stay at a hot spring location for three to four weeks to refresh one's body and mind through bathing. During the Meiji period, modern medicine, which cured illnesses directly, was introduced to Japan, but hot spring treatments continued even after their use became considered outside the scope of medical treatment. In conjunction with changing lifestyles after World War II, the objective of using hot springs shifted from treatment to recreation. On the other hand, as the population decreases and healthcare and nursing costs continue to rise, interest is growing in health tourism as a policy that is beneficial to economic revitalization and accomplishing reasonable healthcare and nursing costs.

In order to use hot springs for health promotion, a certification system for health promotion facilities that utilize hot springs was created in 1989. When using a certified facility generally for at least seven days with a month in accordance with hot spring treatment instructions provided by a consulting doctor at the facility, transportation costs to and from the facility, as well as facility use fees, can be deducted as medical expenses from one's income taxes. As of July 2019, there are 22 health promotion facilities utilizing hot springs across Japan (Note 1).

Based on the case of the Toyotomi Hot Springs (Toyotomi Town, Hokkaido Prefecture), which has the highest number of medical expense deduction applicants among health promotion facilities utilizing hot springs, this paper considers the significance of accumulating and disseminating empirical evidence for promoting health tourism that utilizes hot springs.

Trends after the Toyotomi Hot Springs' Recognition as a Health Promotion Facility Utilizing Hot Springs (Collaborative-type: hot spring and exercise facilities)

The oil tar contained in the Toyotomi Hot Springs, located south of Wakkanai City, was thought to have anti-inflammatory properties against psoriasis and atopic dermatitis, and in the 1990s it became known that the hot springs were beneficial for psoriasis patients. In the 2000s, it was found that they helped atopic dermatitis patients, which led to increases not only in the number of bathing guests, but also in people moving to Toyotomi Town in order to continue their treatment. In July 2017 the Toyotomi Fureai Center and Toyotomi Hot Springs Nature Observatory were recognized as health promotion facilities utilizing hot springs (collaborative-type). A one-way trip to the Toyotomi Hot Springs from Tokyo via Wakkanai Airport in economy class costs roughly 46,000 yen and between 6,000 and 24,000 yen from Sapporo, depending on the means of transportation. It is assumed that the ability to deduct transportation costs and the like as medical expenses increases the number of remote visitors and cause them to extend their bathing stays.

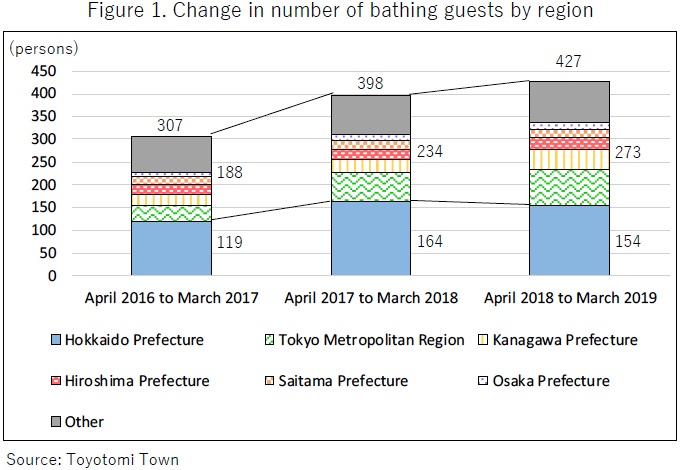

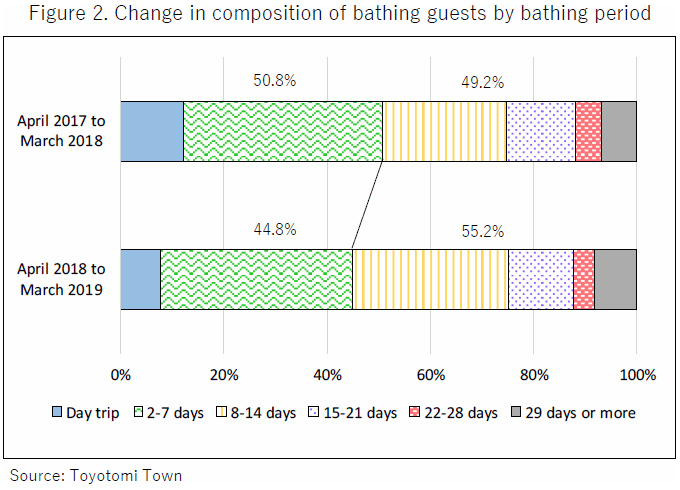

After becoming certified, the number of medical expense deduction applicants who stayed at the Toyotomi Hot Springs was 181 (of which 154 came from outside Hokkaido) in the first year (August 2017 to July 2018) and the figure stayed at the same general level at 178 (148 from outside Hokkaido) in the second year (August 2018 to July 2019), despite the Hokkaido Eastern Iburi earthquake that occurred in September 2019. In both years the proportion of first-time visitors was approximately 30%. Based on aggregate data from bathing treatment cards filled in by guests that also include those who did not apply for a medical expense deduction, it is evident that the number of bathing guests coming from outside Hokkaido (see Fig. 1) and the proportion of bathing guests staying longer than one week (see Fig. 2) both increased. Guests had been influenced by information on the internet (including personal blogs), their doctors, acquaintances, and family members (in that order), some had been directly introduced by their doctors, and many bathing guests visiting from outside Hokkaido came from the Tokyo metropolitan region and Hiroshima Prefecture in particular.

However, the Toyotomi Hot Springs are a special case and before their certification, the number of medical expense deduction applicants was around 50 to 70 per year across all 19 certified facilities nationwide. One factor suppressing increases in applications at other facilities has been analyzed thusly: "Other than facilities announcing the system to their members, there are few opportunities for users to learn about it and because only the use fees can be deducted in the countryside, where most people travel by car, many do not consider the system sufficiently beneficial. Furthermore, there is a large gap between facilities working with medical institutions and those that aren't (Note 2)."

The large number of medical expense deduction applicants at the Toyotomi Hot Springs is likely because the system is particularly suited to its use with that facility, given, for example, the high transportation costs when using public transit and that the facility is easy for doctors to recommend due to the hot springs' known effects and existing evidence that they benefit dermatology patients.

Greater Accumulation and Dissemination of Evidence towards Health Tourism Promotion Involving Hot Springs Is Necessary

Cooperation with doctors, as seen at the Toyotomi Hot Springs, is also important when it comes to the promotion of hot spring health tourism. An essential requirement for this is the accumulation and dissemination of evidence that demonstrates the treatment benefits of hot springs to doctors.

Research on hot spring treatments in Japan is primarily carried out by the Japanese Society of Balneology, Climatology and Physical Medicine and the Japan Health & Research Institute. However, national hospitals, research institutes and hospitals affiliated with national universities that formerly handled the majority of hot spring treatment research and clinical practice have all been abolished or restructured, making it difficult to gather empirical evidence. Only a small number of medical departments at universities hold lectures regarding hot spring treatments, and there are only approximately 1,000 doctors who have received training regarding hot spring treatment methods, out of approximately 320,000 doctors nationwide, which also limits the dissemination of such evidence.

In France, 65% of hot spring treatment costs are covered by medical insurance as long as the patient stays for three weeks (exclusive of Sundays, 18 days of treatment) at a hot spring health resort listed on a medical certificate issued by a doctor. When France considered revising medical insurance coverage for hot spring treatment costs due to financial constraints in the 2000s, 2 euros collected from every hot spring patient and capital from the National Association of Mayors of Hot Spring Towns were used to fund subsidies issued by the French Association for Thermal Research to research projects studying the treatment effects of hot springs beginning in 2004. Until 2018, through treatment service evaluations, clinical trials, and research carried out as part of 51 research projects funded with 13.1 million euros, France gathered and disseminated empirical evidence, including that symptoms of patients with arthritic knees improved more among those who had undergone hot spring treatment than among those who had received regular treatment, and gained insights applicable to insurance coverage. In 2018, 600,000 patients underwent hot spring treatment covered by medical insurance at 110 hot spring health resorts (Note 3).

In Japan, too, there is demand for improved structures for accumulating and disseminating empirical evidence after creating budgetary measures such as collecting funds from hot spring patients. In terms of funding, cities, towns, and village are the principal tax-collecting entities and uniform adjustments on a national scale would likely be necessary, but one option could be to increase the bathing tax (standard: 150 yen per person per day) levied on mineral spring bath guests (an increase of 10 yen can be expected to raise approximately 1.5 billion yen in tax revenue).

The Ministry of the Environment in 2017 proposed new forms of medical bathing as a hot spring use commensurate with modern lifestyles and began a scientific examination of the health benefits and the like of hot spring locations in general. In FY2018 it carried out an initial survey of 20 hot spring locations and facilities across the country and confirmed that visits to hot spring locations were able to achieve positive changes to body and soul (Note 4).

However, the FY2018 survey by the Ministry of the Environment primarily featured questions asking about subjective changes to respondents' health status before and after their visit to a hot spring location. In order to disseminate the treatment benefits of hot springs to medical doctors, it is essential to also gather and spread empirical evidence. I hope that in anticipation of an age of 100-year human lifespans, we will not only harness the powers of hot springs in reducing stress and revitalizing visitors, but also further accumulate and disseminate evidence to increasingly utilize the powers of hot springs.