I. Introduction

The U.S.-China economic confrontation, which began in 2018 in the form of trade friction, has been widening and deepening ever since. Both countries have positioned it as a top priority policy issue regarding economic security, and are taking comprehensive measures to address it. Meanwhile, Japan, in concert with the U.S., is trying to rein in China as part of its effort to strengthen economic security.

Against the backdrop of China's emergence as an economic superpower while maintaining a political-economic system that differs from that of the West, the Trump administration, which came into office in 2017, shifted U.S. policy toward China from “engagement” to “decoupling”. Under the engagement policy, the U.S. supported China's economic development and, through this, aimed to change China's political-economic system, but under the decoupling policy, the U.S. restricted economic exchanges between the two countries in order to limit Chinese ambition. This stance has been carried over to the Biden administration, which came into power in 2021.

In its 2022 “National Security Strategy,” the Biden Administration identified China as “ the only competitor with both the intent to reshape the international order and, increasingly, the economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to do it (Note 1).” It also stated that to counter China's threat to U.S. economic security, including its control over key technologies and supply chains, the United States must work with allies and partners to stop the flow of advanced technologies to China through regulating trade, investment, and other activities (Note 2).

China, which is on the defensive against the U.S. offensive, is preparing for a prolonged economic war. Specifically, while taking corresponding retaliatory measures, it is advancing a “dual circulation strategy,” in which “domestic circulation is the mainstay and the domestic and international circulations reinforce each other.”

Amid the lingering economic confrontation, the decoupling trend between China and the U.S. has become more and more apparent. The impact is not limited to the two countries directly involved, but also extends to third countries through the slowdown of international trade and investment, and the fragmentation of supply chains. In particular, Japan, which aligns its economic security policy with its ally, the United States, will inevitably decouple from China, to one extent or another.

II. The United States on the Offensive

To rein in China, the U.S. is implementing sanctions against China and working to strengthen its economic security, focusing on preventing the outflow of advanced technology to China and strengthening its industrial policy.

1. Tightening trade restrictions

The U.S. is restricting trade with China in terms of both imports and exports.

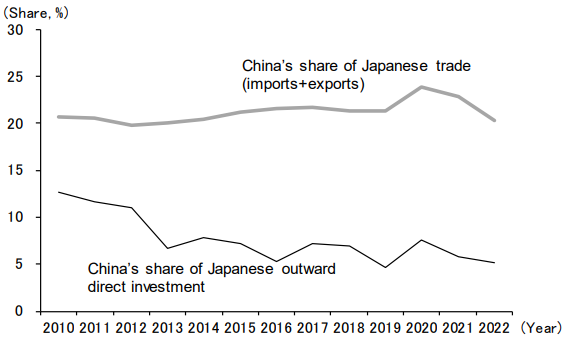

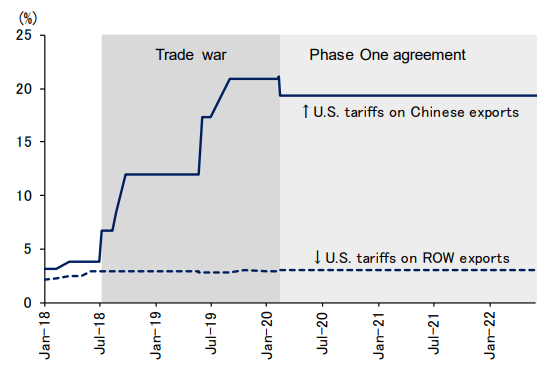

On the import front, first, on March 22, 2018, the Trump administration decided to impose sanctions against China, primarily the implementation of additional tariffs under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 (Note 3). From July 2018 to 2019, the U.S. gradually expanded the scope of additional tariffs (up to 25%) to about two-thirds of imports from China (in value terms, calculated based on 2017 figures). As a result, the average tariff rate on imports to China rose from the previous 3.8% to a peak of 21.0%. Although some rates of additional tariffs on imports from China were reduced following the signing of the first phase of the U.S.-China Economic and Trade Agreement on January 15, 2020, more than two years after the Biden administration took office, the average tariff rate on imports remains high at 19.3%, well above the tariff rate applied to countries and regions other than China (3.0% on average) (Figure 1).

In addition, the U.S. is regulating imports of some Chinese products due to human rights abuses and forced labor. Specifically, the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, a law that in principle bans the import of products produced in the Xinjiang Uyghur autonomous region in China, was passed on December 23, 2021, and the import ban based on this law went into effect on June 21, 2022. As a result, importers who intend to import Uyghur products now bear the burden of proving that the subject products are not related to forced labor. In addition, products from third countries that contain raw materials or parts related to the Xinjiang Uyghur autonomous region are also subject to the import ban.

On the other hand, export controls to China can be broadly classified into two main categories: item-based controls and end-user-based controls.

Item-based export controls are centered on the U.S. Export Administration Regulations (EAR), which apply to exports of commercial products known as “dual-use items” that can be used for both military and non-military purposes and are administered and regulated by the Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) of the U.S. Department of Commerce. In August 2018, the Export Control Reform Act of 2018 (ECRA) was enacted as part of the John S. McCain National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019, strengthening export controls. Specifically, “emerging and foundational technologies” not captured by previous export controls will now be subject to control. Not only direct exports of such technologies from the U.S., but also exports through third countries (re-exports) will require BIS approval.

End-user-based controls on exports in the U.S. are centered on the Entity List published by the BIS, which lists entities that are categorized as contrary to U.S. national security and foreign policy interests, as well as entities of concern for proliferation of weapons of mass destruction (WMD). If an entity wishes to export or transfer certain items, such as certain U.S. technology, to an entity on the list, it must apply to the BIS for a permit. Amid escalating trade friction between the U.S. and China, a number of Chinese companies suspected of involvement in the military-civilian fusion policy or human rights abuses in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, in addition to Chinese telecommunications equipment giant Huawei Technologies, were placed on this list and subject to export restrictions by the U.S. (Note 4).

2. Tighter restrictions on inward and outward foreign direct investment

The U.S. government believes that restricting inward and outward FDI is an effective means of preventing the flow of technology into China.

The Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018 (FIRRMA), included in the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019, strengthens the authority of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) and tightens regulations that are applicable to investments by foreign companies in U.S. companies with critical technology and in industrial infrastructure. With the implementation of the law, for projects involving these areas, in addition to conventional investments by foreign companies that “control” U.S. companies, non-passive investments (investments in which even a small investment can provide access to non-public technical information held by the U.S. company, participation or involvement on the board of directors, etc.) are now also subject to review.

Meanwhile, in recent years, public opinion advocating that U.S. companies' investment in China should be restricted has been growing in the U.S. First, the annual report of the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, a congressional advisory committee, released in November 2021, recommended restrictions on outward investment (Note 5). The National Critical Capabilities Defense Act of 2022 (as amended), agreed to by a bipartisan group of lawmakers in the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives in June 2022, includes a provision to establish a new interagency committee to review, and in some cases, to prohibit outward investment in designated “countries of concern,” including China, for national security reasons (Note 6). Moreover, in March 2023, the Biden administration reportedly began preparing a presidential decree banning U.S. investment in certain sectors in China as a new measure to protect U.S. technological advantages in the face of increasing competition between the United States and China (Note 7).

3. Tighter regulations targeting the telecommunications industry

The U.S. is tightening its restrictions in an effort to exclude Chinese telecommunications equipment companies, citing the need to prevent the leakage of personal and sensitive information. China's National Intelligence Law stipulates that “any organization or citizen shall give support, assistance, and cooperation for national intelligence activities in accordance with the law.” On this basis, the U.S. claims that Chinese telecommunications equipment companies and carriers are forced to cooperate with China's public security and national security agencies even when doing business outside of China, creating security vulnerabilities for foreign countries and companies using their equipment and services (Note 8). The U.S. restrictions on telecommunications equipment companies cover imported products, while the restrictions on telecommunications carriers cover services provided in the U.S., effectively limiting direct investment.

The National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 included a provision that prohibits government procurement of telecommunications equipment and other products from five Chinese companies. The targeted companies (including their affiliates) and products are (1) telecommunications equipment made by Huawei and ZTE, and (2) video surveillance and communications equipment for security purposes made by Hytera Communications, Hangzhou Hikvision Digital Technology and Dahua Technology. The ban was implemented in two phases. In the first phase beginning in August 2019, the government was prohibited from procuring, acquiring, using, contracting, and extending or renewing contracts for telecommunications equipment and services that have these products and services as key components or critical technologies. In the second phase, beginning in August 2020, the government was prohibited from contracting with, or extending or renewing contracts with, companies that use telecommunications equipment or services that use these products or services as key components or key technologies.

In addition, the Secure and Trusted Communications Network Act, which was passed on March 12, 2020, prohibits U.S. telecommunications companies from using public funds to purchase equipment from companies that pose a national security threat and requires the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to publish a list identifying such equipment and services. The list includes equipment from five companies already excluded from government procurement under the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 (listed on March 12, 2021), plus the telecommunications carriers China Telecom Americas (listed on March 25, 2022), China Mobile International USA (listed on September 20, 2022), China Unicom Americas (listed on September 20, 2022), and Pacific Networks and its wholly owned subsidiary Comnet (listed on September 20, 2022) (Note 9). In parallel, the FCC rejected China Mobile's business license application in May 2019, followed by the revocation of China Telecom's business license in October 2021, China Unicom in January 2022, and Pacific Networks and ComNet in March 2022 (Note 10).

Furthermore, on November 11, 2021, the Secure Equipment Act of 2021 was passed, and pursuant to its provisions, the FCC issued an Executive Order on November 25, 2022, prohibiting the certification of telecommunications equipment for importation into or sale within the United States that could pose a national security threat. This includes communications equipment and surveillance cameras manufactured or provided by Huawei and ZTE, as well as surveillance cameras and communications equipment manufactured or provided by Hytera, Hikvision, and Dahua that have national security applications.

4. Tighter restrictions on semiconductor-related exports to China

Given the importance of semiconductors in areas closely related to national security, such as military, aerospace, and computers, the United States has tightened restrictions on China's access to semiconductor technology and manufacturing equipment.

First, on December 18, 2020, the BIS placed China's largest semiconductor manufacturer, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC), on its entity list, prohibiting it from selling without a license most equipment capable of producing semiconductors at 10 nanometers (nm) or smaller. Following that, in July 2022, it extended this restriction to all equipment capable of producing semiconductors at 14 nm and below bound for China (Note 11).

In addition, on August 15, 2022, the BIS added certain semiconductor-related technologies and other items to the scope of export controls, based on the agreement reached at the 2021 Plenary Meeting of the Wassenaar Arrangement on Export Controls for Conventional Weapons and Related General-Purpose Goods and Technologies (Note 12).

In addition, on October 7, 2022, the BIS announced a number of regulatory measures on the export of advanced semiconductor technology to China (Note 13). The export ban applies to not only semiconductors and manufacturing equipment for the development of Chinese supercomputers and the development and production of integrated circuits, but also all semiconductor contract manufacturing services for Chinese companies designated by the US government, after-sales services for advanced manufacturing equipment already in operation in China, and services provided by U.S. citizens in China that relate to advanced know-how. In response, on December 16, 2022, BIS added major Chinese semiconductor manufacturer Yangtze Memory Technologies Corp. (YMTC) and 21 major semiconductor manufacturers for artificial intelligence to the entity list (Note 14).

And on January 27, 2023, the United States agreed with Japan and the Netherlands to regulate exports of advanced semiconductor manufacturing equipment to China (Note 15). In response, following the Netherlands (on March 8, 2023), Japan announced on March 31, 2023, in line with the U.S., that it would tighten export controls on advanced semiconductor manufacturing equipment, with China in mind, from a national security perspective.

5. Tighter regulation of the financial sector

In the area of finance, the U.S. government has placed restrictions on the purchase of Chinese securities by U.S. investors and the procurement of funds in the U.S. by Chinese companies (Note 16).

First, President Trump signed an Executive Order on November 12, 2020, prohibiting U.S. companies and individuals from investing in securities of 31 companies owned or controlled by the Chinese People's Liberation Army (Note 17). In response, the sanctioned Chinese state-owned telecommunications companies China Mobile, China Telecom, and China Unicom were forced to delist from the New York Stock Exchange (May 2021).

Meanwhile, the Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act, which requires listed Chinese companies to disclose information, was enacted on December 18, 2020. The Act imposes on foreign companies listed on U.S. stock exchanges the obligation to prove that they are not owned or controlled by a foreign government, and prohibits trading in the securities of such companies if the U.S. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) fails to conduct an inspection for three consecutive years (Note 18). The PCAOB then announced a list of foreign issuers that it is unable to inspect, all of which are Chinese (including Hong Kong) companies. On August 12, 2022, five companies on this list—Chinese Life Insurance, Aluminum Corporation of China (Chalco), China Aluminum, Sinopec, PetroChina, and Sinopec Shanghai Petrochemical Co—announced plans to delist their American depositary shares on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE). As a result of negotiations between the U.S. and China in response to this situation, the financial authorities of both sides agreed to cooperate in conducting inspections on August 26, 2022. This has averted, for the time being, the risk of Chinese companies being shut out of the U.S. market. (Note 19)

6. Strengthening industrial policy

The Biden administration has emphasized industrial policy, passing the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the CHIPS and Science Act (hereinafter, CHIPS Act), and the Inflation Reduction Act to increase the budget for infrastructure investment and industrial support.

First, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, enacted on November 15, 2021, includes measures that will add a total of $550 billion to the existing baseline in the federal budget over the next five years. In transportation sector infrastructure, this includes $110 billion for road and bridge improvements, $66 billion for passenger and freight rail improvements, and $15 billion for the construction of 500,000 EV (electric vehicle) charging facilities nationwide. In non-transportation sector infrastructure, the main expenditures will be $55 billion for water infrastructure, $65 billion for broadband networks, and $65 billion for electricity grid networks.

The CHIPS Act, enacted on August 9, 2022, includes a $52.7 billion budget to support semiconductor manufacturers and tax incentives to encourage investment in semiconductor production, as well as $200 billion to support scientific research in artificial intelligence, robotics, quantum computing, and other advanced fields. Most of the subsidies for semiconductor manufacturers are expected to go to companies such as Intel Corporation of the United States, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), and Samsung Electronics of South Korea, which are building new semiconductor plants in the United States. Companies receiving subsidies must promise not to increase production of advanced semiconductors in China over the next decade.

In addition, the Inflation Reduction Act, passed on August 16, 2022, provides for $369 billion over 10 years (FY2022-FY2031) through tax credits and grants in the area of energy security and climate change. Of this amount, $160.3 billion is in tax credits for clean power.

7. Strengthening ties with allies

As part of its decoupling policy toward China, the Biden administration is working to strengthen cooperation with its allies. The centerpiece of this effort is the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), a new regional economic initiative launched on May 23, 2022, during President Biden's visit to Japan. Participating countries include the United States, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, India, Fiji, and seven ASEAN countries (Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam). At a ministerial meeting in September 2022, the participating countries decided to begin formal negotiations in four areas: (1) supply chains, (2) trade, (3) clean economy including energy security, and (4) fair economy including anti-corruption.

III. China Preparing for a Prolonged Economic War.

China, on the defensive against the U.S. offensive, is taking retaliatory measures and strengthening its economic security in preparation for a prolonged economic war.

1. Tightening of trade restrictions

On the trade front, China has introduced an “Unreliable Entity List” system and enacted an “Export Control Law” in addition to implementing additional tariffs targeting imports from the United States.

First, in response to a series of additional tariffs implemented by the U.S. on imports from China under the Trump administration, China implemented additional tariffs on imports from the United States as a countermeasure. As of April 2023, the scope of these tariffs reached 58.3% of imports from the United States, reflecting an average tariff rate of 21.1%, up from 7.2% before the tariffs were introduced (Figure 2).

Second, on September 19, 2020, the “Unreliable Entity List” system was promulgated and implemented to sanction foreign companies and other entities that have suspended transactions with Chinese companies in violation of the “principles of normal market transactions,” by restricting their trade and investment transactions with Chinese entities (Note 20).

Additionally, the Export Control Law, which went into effect on December 1, 2020, strengthens export controls on goods, technology, services, data, and other items related to the protection of national security and interests and the fulfillment of international obligations such as non-proliferation. Although export control regulations on dual-use items, military equipment, and nuclear weapons already existed in China, the Export Control Law was enacted as a basic law to comprehensively regulate exports from the perspective of security trade control.

2. Tighter regulations on inward direct investment

The Foreign Investment Law (effective January 1, 2020) clearly states that the government will examine foreign capital investments that may have a negative impact on national security. The Measures for Security Reviews on Foreign Investments (effective January 18, 2021), which provides detailed regulations for examination, stipulates that the government will review foreign capital investments in the following areas: (1) investments in areas related to national defense security, such as military and auxiliary military industries, and investments in military facilities and areas surrounding military facilities; (2) investments in areas related to national safety, such as important agricultural products, important energy and resources, important infrastructure, important transportation services, important cultural products and services, critical information technology and Internet products and services, critical financial services, key technologies, and other critical sectors, and investments in which the foreign investors acquire effective control of the investee company.

3. Strengthen cyber security and data security

China has positioned cyber and data security as an important part of its economic security policy and is taking measures such as the development of related laws.

First, the Cyber Security Law, which went into effect on June 1, 2017, requires network operators, Internet product and service providers, and critical information infrastructure facility operators in China to establish security management systems and protect the security of critical infrastructure and critical data. In particular, critical information infrastructure operators are required to store personal information and critical data collected or generated in China within China, and must undergo security assessments when transferring such data overseas. The authorities will conduct security supervision and inspections and may issue remedial instructions and punishments in cases of inadequate compliance.

On the basis of the Cyber Security Law, authorities announced on March 31, 2023 that they will investigate the cyber security of products sold in China by the U.S. semiconductor giant Micron Technology (Note 21). This is seen as a retaliatory action against Micron Technology for the U.S. placing their competitor in China, Yangtze Memory Technologies (YMTC), on the U.S. Entity List.

The Data Security Law, which went into effect on September 1, 2021, requires that the government (1) establish a data security review system and conduct national security reviews of data handling activities that affect or may affect national security, (2) implement export controls under the Law for data that falls under regulated items related to the maintenance of national security and interests and the fulfillment of international obligations, and (3) prohibit, restrict, or take other commensurate measures against foreign entities from countries or regions which discriminate against China in investment, trade, or other activities involving data or data development and use technologies.

In addition, the Anti-espionage legislation, passed in 2014, was amended on April 26, 2023 (effective July 1, 2023). The amended law adds cyber-attacks against government agencies and intelligence infrastructure to the definition of espionage and prohibits foreign nationals from possessing state secrets, including any documents, data, materials, or articles related to national security. In response to this amendment, an increasing number of foreigners have been detained by authorities in China on espionage charges.

Finally, the Chinese authorities are reportedly restricting or outright cutting off foreign access to various databases involving corporate-registration information, patents, procurement documents, academic journals, and even official statistical yearbooks (Note 22).

4. Legislation to address sanctions

China has been making laws and regulations to address sanctions imposed by the United States and other foreign countries. First, the Rules on Counteracting Unjustified Extraterritorial Application of Foreign Legislation and Other Measures, which went into effect on January 9, 2021, states that in order to protect national sovereignty, security, and development interests, etc., the government may take measures to prevent the effects of the improper extraterritorial application of foreign laws and regulations. The Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law, which went into effect on June 10, 2021, provides the right to take appropriate countermeasures against foreign governments and entities that discriminate against Chinese citizens and organizations and interfere in China's internal affairs. While the Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law is an outward-looking measure, intended to respond to sanctions imposed by other countries or international organizations, the Rules on Counteracting Unjustified Extraterritorial Application of Foreign Legislation and Other Measures is an inward-looking measure, intended to prevent the improper application of foreign laws and measures in China.

5. Diversification of export markets and promotion of the “Belt and Road Initiative”

Through its promotion of the “Belt and Road Initiative” and its accession to the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement, China is working to reduce its dependence on the United States and other developed markets and diversify its export markets.

“Belt and Road” is a China-led initiative to create an economic zone spanning the continents of Asia, Europe, and Africa. The Silk Road Fund and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) have been established to provide financial support for infrastructure development in the target regions. The “Belt and Road Initiative” is a Chinese-version of the Marshall Plan, which contributed greatly to the post-World War II reconstruction of Western countries and provided a huge overseas market for U.S. companies.

RCEP is an economic partnership agreement among China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, and 10 ASEAN countries. The member countries account for about 30% of the world's GDP, total trade, and population. The elimination of most tariffs applicable to trade among the member countries and the relaxation of investment restrictions will make it easier for Chinese companies not only to access markets but also to establish cross-border production networks.

6. Industrial policy and promotion of a “dual circulation strategy”

To gain an edge in competition with the United States, China is actively pursuing industrial policies such as “military-civilian fusion,” “China Manufacturing 2025,” and a “dual circulation strategy.”

First, China has long promoted “military-civilian fusion,” but it has positioned this as a national strategy since the Xi Jinping administration came to power. The aim is to promote the use of civilian resources for military purposes and the conversion of military technology to civilian use.

In addition, in order to become a “manufacturing powerhouse,” the Chinese government announced the “China Manufacturing 2025” plan on May 19, 2015, which lays out a medium- to long-term vision for the development of the manufacturing industry (Note 23). It includes nine strategic missions, including improving the innovation capacity of the manufacturing industry and promoting the advanced integration of informatization and industrialization, and ten priority areas including next-generation information technology, advanced digitally-controlled machine tools and robots, and aerospace equipment.

Furthermore, as a pillar of its 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025), China is promoting a “dual circulation strategy” with “the domestic circulation as the mainstay and the domestic and international circulations reinforcing each other,” taking advantage of being a large country. The essence of the “dual circulation strategy” is to reduce dependence on international circulation and strengthen domestic circulation in terms of both supply and demand, while maintaining openness to the outside world. To achieve this, it is necessary to expand domestic demand, particularly consumption, and to implement supply-side reforms aimed at raising productivity through innovation and industrial upgrading. In terms of the “smiling curve,” which represents the level of value-added of each process in the supply chain, the shift from international to domestic circulation will be achieved mainly by shifting the upstream suppliers of technology, parts, and intermediate goods and the downstream buyers of products from overseas to domestic markets.

IV. Expanding Decoupling from U.S.-China to Japan-China

The U.S.-China economic decoupling is casting a large shadow over the global economy through the fragmentation of supply chains and the slowdown of international trade and investment, with a particularly large impact on Japan, which also has deep economic ties with both the United States and China. Signs of Japan-China decoupling are also beginning to emerge as Japan has begun to actively engage in reining in China in line with the United States.

1. U.S.-China decoupling gathering pace

The U.S.-China decoupling trend has become more and more apparent especially in trade and direct investment.

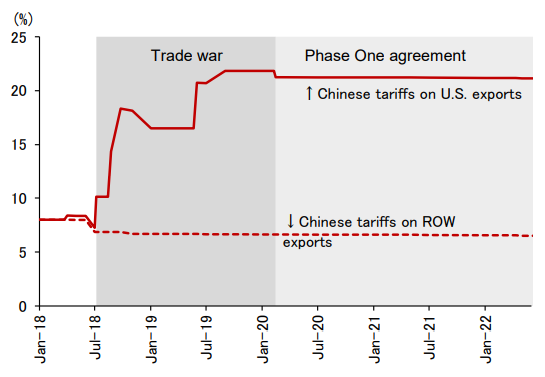

First, for the United States, China was the largest trading partner for four years from 2015 to 2018, but fell to third place in January-March 2023, behind Mexico and Canada (Figure 3). China's share of U.S. imports and exports also fell from a peak of 16.3% in 2017 to 11.0% in January-March 2023. In the U.S. market, some imports from China are being replaced by imports from countries and regions that compete with China, such as Vietnam, Taiwan, India, and South Korea. Many multinational companies are moving their production to other countries to avoid tariffs and other trade barriers that target only China.

- Country's share of total U.S. imports and exports -

Source: Compiled by the author based on U.S. Census Bureau Statistics.

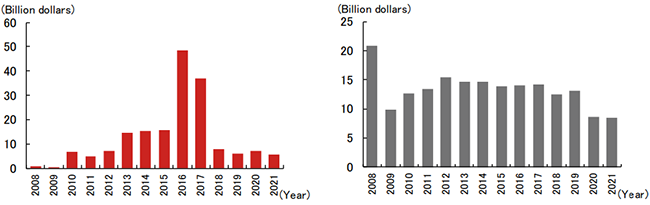

In addition to trade, direct investment between the U.S. and China has also become stagnant (Figure 4). In particular, China's direct investment in the U.S., especially in M&As targeting high-tech companies, has declined significantly in the wake of stricter regulations on inward direct investment by the U.S. introduced by the Trump administration. For China, as a developing country, introducing technology from abroad at low cost has been one of the factors that has led to its high growth, with inward and outward FDI being the most important routes. Losing its latecomer's advantage before it becomes a developed country will be a major constraint on growth in the medium to long term.

[Click to enlarge]

Of course, U.S.-China decoupling will be very damaging not only to China but also to the United States. China is a key player in global supply chains, and U.S.-China trade and U.S. firms' production in China include many intermediate goods and components in addition to final consumer goods. If the U.S.-China decoupling proceeds, many U.S. companies will be forced to exit China and switch their investment destinations and import sources to countries with higher costs than China. As a result, the U.S. will not only lose the Chinese market, but import prices will rise and the competitiveness of its own industries will decline. Furthermore, in the financial sector, many Chinese companies will exit the U.S. stock market, which will be a blow to the capital markets as well.

2. Japan caught between the U.S. and China

New U.S. and Chinese regulations and measures introduced against the backdrop of the U.S.-China conflict have affected Japanese companies in the following ways.

First, Japan is caught between the rules initiated by the U.S. and China. If the U.S. government imposes sanctions against China, the Japanese government may have no choice but to follow suit. However, Japanese companies that cooperate with U.S. sanctions against China may be subject to sanctions by China. As in the semiconductor industry, some Japanese companies are being forced to choose between the U.S. and China.

In addition, the additional tariffs of up to 25% that the U.S. government has imposed on products imported from China also apply to products produced in China by Japanese firms. This means that for Japanese companies, China has lost its advantage as an export base to the United States. On the other hand, the additional tariffs targeted by the Chinese government on imports from the United States also apply to products made in the United States by Japanese firms.

Furthermore, U.S. export controls may also apply to products of third countries that import U.S. products and “re-export” products incorporating U.S. products as parts, etc. As one example, not only direct exports from the United States to Huawei, which is on the Entity List, but also exports to Huawei of many Japanese products that incorporate U.S.-made parts, etc., are subject to U.S. export controls.

And Japanese companies that use products, parts, or software from China may be shut out of the U.S. market due to U.S. sanctions. For example, with the implementation of the U.S. “Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act,” not only products made in Xinjiang, but also Japanese products using raw materials produced in Xinjiang are subject to the U.S. import ban. In this case, the impact on the apparel industry, which relies heavily on Xinjiang cotton, is particularly significant. In order to circumvent the restrictions, Japanese companies will have to shift their raw material procurement to other regions, which will inevitably lead to higher costs.

Japanese companies are affected not only by the U.S.-China conflict, but also by the Japanese government's ongoing economic security efforts.

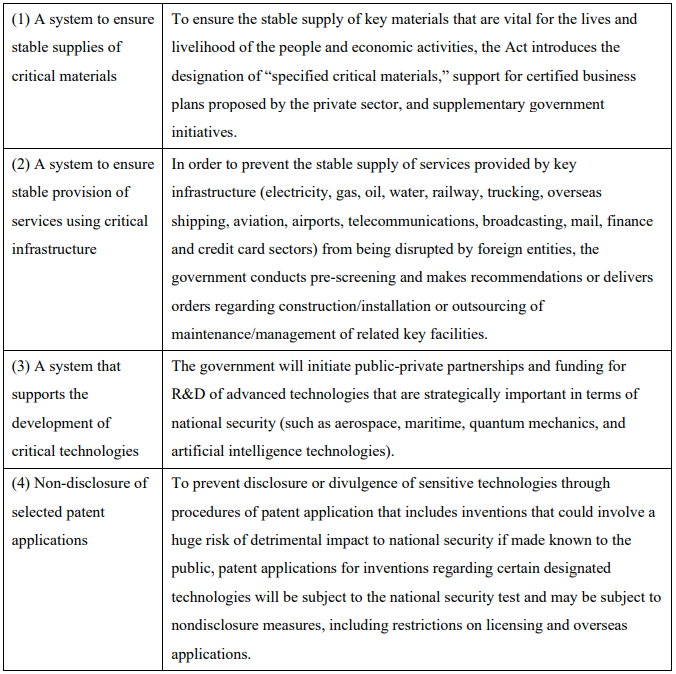

On May 11, 2022, the “Act on the Promotion of National Security through Integrated Economic Measures” (“Economic Security Promotion Act”) was enacted, which consists of four pillars: (1) a system to ensure stable supplies of critical materials, (2) a system to ensure stable provision of services using critical infrastructure, (3) a system that supports the development of critical technologies and (4) non-disclosure of selected patent applications. (Table 1). Although the “Economic Security Promotion Act” does not refer to China by name, it is clear from its enactment process and content that it is directed toward China. In fact, in order to comply with the requirement to ensure stable provision of services using critical infrastructure, there is a growing trend among financial institutions to consider withdrawing from China or transferring their system-related and personal information-handling operations to Japan (Note 24).

Source: Compiled by the author from the “Act on the Promotion of Security Assurance through Integrated Economic Measures” (Act No. 43 of 2022).

Next, to strengthen supply chains and reduce economic security risk, the Japanese government is currently encouraging the relocation of production bases from China to ASEAN and Japan through the promotion of the “Overseas Supply Chain Diversification Support Project” and the implementation of the Program for Promoting Investment in Japan to Strengthen Supply Chains.” In addition, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation (TSMC) will build a semiconductor plant in Kumamoto Prefecture in collaboration with Sony Group and Denso, with a total investment of approximately 1.1 trillion yen, of which the Japanese government will provide up to 476 billion yen in subsidies (Note 25). Because of its large scale, the new project is expected to create jobs and semiconductor clusters in the surrounding areas. In addition, it will provide viable alternative business partners for upstream and downstream Japanese companies seeking to reduce their dependence on China.

And as part of the strengthening of export controls, the government followed in the footsteps of the U.S. and announced on March 31, 2023 that 23 items, including manufacturing equipment for advanced semiconductors, will be added to the list of controlled items (to be enforced after soliciting public comments and revising ministerial ordinances under the Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Law) (Note 26). The 23 items to be added will require individual export permits, except for those destined for 42 countries and regions, including friendly countries, making export to China virtually impossible. Chinese demand in these sectors is significant, and it will not be easy to develop new markets to replace the items.

Finally, the revised “Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Act” (hereinafter referred to as the “Foreign Exchange Act”) went into effect on May 8, 2020, in order to strengthen restrictions on foreign capital investment in key industries. Under the Foreign Exchange Law prior to the revision, foreign investors were required to make a prior declaration and undergo an examination in the relevant field in order to acquire 10% or more of the shares of a company in a “designated industry” related to Japan's “national security,” “public order,” “public safety,” or “smooth operation of the economy,” but after the revision, this threshold was lowered to 1% (Note 27). Among the “designated industries,” “core industries” (arms, aircraft, space-related, nuclear power-related, general-purpose products that can be converted to military use, cyber security-related, electric power, gas, telecommunications, water supply, railroads, and petroleum) that are subject to particularly intensive screening, are specified. 2020 saw the addition of infectious disease-related pharmaceuticals and medical equipment, and in 2021, industries related to important mineral resources such as rare earths were also added. In conjunction with the implementation of the revised Foreign Exchange Law, the government has published a list of companies that are required to submit prior notification when receiving investments from foreign investors. In its latest version (released on November 2, 2021), of the 3,849 listed Japanese companies, 801 are classified as core industries and 1,161 as designated industries outside the core industries (Note 28). While M&A targeting Japanese companies by Chinese investors has been rare, the implementation of the revised “Foreign Exchange Law” has made it even more difficult.

In order to respond to the series of measures being taken by Japan, the U.S., and China to strengthen economic security, Japanese companies must strengthen their compliance and risk management systems by focusing on information gathering, supply chain risk assessment, and internal information management. However, because supply chains are intricately intertwined across borders, and the range of goods and services and trading partners that are restricted frequently change, these measures require massive investment of resources, including both human and financial resources.

In addition, many Japanese companies are restructuring their supply chains by diversifying and switching suppliers, expanding domestic production capacity, restructuring overseas production networks, reviewing export destinations and business partners, and reviewing R&D systems. As a result, there is a growing trend among Japanese companies toward withdrawing business from China and separating U.S. and Chinese operations. According to a survey by Teikoku Databank, the number of Japanese companies operating in China was 12,706 in June 2022, 940 fewer than at the time of the 2020 survey, mainly reflecting the withdrawal of business (Note 29). According to a survey conducted by the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) in 2022, 19% of the surveyed Japanese manufacturing companies have already completed the process of separating their U.S.-bound and China-bound businesses against the backdrop of U.S.-China friction, and 6% more are moving in that direction. While 54% of the companies surveyed say they “would strengthen both their Chinese and U.S. operations,” the percentage that say they “would rather strengthen their Chinese operations,” (11%) is much lower than the percentage that say they “would rather strengthen their U.S. operations” (23%) (Note 30).

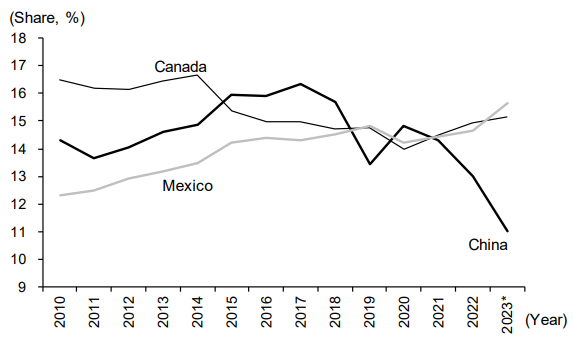

Thus, following the U.S.-China decoupling, we expect to see more Japan-China decoupling in the future (Note 31). As a sign of this, China's shares of Japan's trade and outward direct investment declined in 2021 and again in 2022 (Figure 5). Since China is Japan's largest trading partner and the two economies are deeply linked through supply chains and other channels, through shrinking export markets and rising import prices, the Japan-China decoupling will put further downward pressure on the Japanese economy, which has stagnated over the last thirty years.