As symbolized by the decision in March 2018 by the United States to impose sanctions on China based on Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974, the U.S.-China dispute over economic issues is intensifying. The conflict between China, which is catching up rapidly with developed countries by introducing technologies from abroad, and the United States, which regards this as a threat, is becoming increasingly conspicuous. Against this backdrop, the focus of the row is shifting from the bilateral trade imbalance to technology transfer.

The United States is accusing China of imposing restrictions on investments by U.S. companies trying to advance into the Chinese market in some industries and for supporting Chinese companies' acquisitions of foreign companies possessing cutting-edge technologies as part of its industrial policy, as exemplified by the Made in China 2025 initiative, and it is calling for corrective measures. At the same time, the United States is strengthening its national security review system regarding foreign investments in U.S. companies, and the number of cases in which Chinese companies had to abandon plans to acquire U.S. companies because of failure to obtain approval from the U.S. authorities has been on the rise.

Imposition of sanctions on China based on Section 301 of the Trade Act

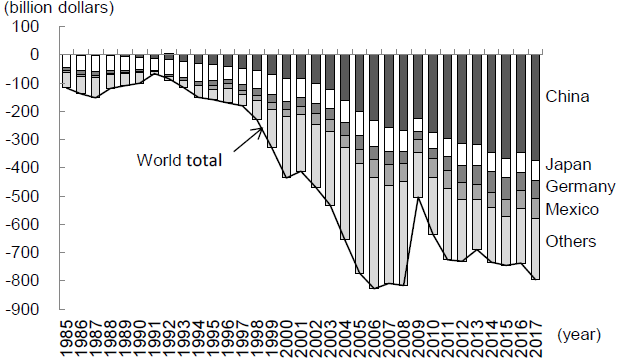

The protectionist tendency of U.S. trade policy has become increasingly prominent since President Donald Trump took office. The United States' protectionist initiative has been targeted mainly at China, a trading partner with which the United States has been recording the largest bilateral trade deficit since 2000. In 2017, the U.S. trade deficit with China amounted to $375.2 billion, or 47.1% of its total trade deficit (Figure 1). The U.S. Department of Treasury kept China on the list of countries that should be closely monitored in the "Macroeconomic and Foreign Exchange Policies of Major Trading Partners of the United States" report in the first half of 2018 on the grounds that the country accounts for a large and disproportionate portion of the U.S. trade deficit (Note 1).

In addition, upon instruction from President Trump, the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) conducted investigations into China's acts, policies, and practices concerning technology transfer, intellectual property, and innovation based on Section 301 of the trade act (hereinafter referred to as the "Section 301 investigation"), starting in August 2017 (Note 2). The report on the investigation results, which was announced on March 22, 2018, is a scathing critique of China. What is notable about the report is that the focus of argument is on technology transfer, rather than on the trade imbalance (Note 3).

The report argued the following points:

First, China uses foreign ownership restrictions, including joint venture requirements, equity limitations, and other investment restrictions, to require or pressure technology transfer from U.S. companies to Chinese entities. China also uses administrative review and licensing procedures to require or pressure technology transfer, which, inter alia, undermines the value of U.S. investments and technology and weakens the global competitiveness of U.S. firms.

Second, China imposes substantial restrictions on, and intervenes in, U.S. firms' investments and activities, including through restrictions on technology licensing terms. These restrictions deprive U.S. technology owners of the ability to bargain and set market-based terms for technology transfer. As a result, U.S. companies seeking to license technologies must do so on terms that unfairly favor Chinese recipients.

Third, China directs and facilitates the systematic investment in, and acquisition of, U.S. companies and assets by Chinese companies to obtain cutting-edge technologies and intellectual property and to generate large-scale technology transfer in industries deemed important by Chinese government industrial plans.

Finally, China conducts and supports unauthorized intrusions into, and theft from, the computer networks of U.S. companies. These actions provide the Chinese government with unauthorized access to intellectual property, trade secrets, or confidential business information, including technical data, negotiating positions, and sensitive and proprietary internal business communications, and they also support China's strategic development goals, including its science and technology advancement, military modernization, and economic development.

In light of the investigation results, President Trump issued the following orders: (1) the Office of the USTR should announce a list of products subject to additional tariffs within 15 days from the announcement of the report on March 22; (2) the Office of the USTR should initiate dispute settlement procedures based on the World Trade Organization (WTO) agreement in order to deal with China's discriminatory technology licensing practices and report on the progress within 60 days; (3) the Treasury secretary should deal with problems related to Chinese investments in industries and technologies critical for the United States and report on the progress within 60 days (Note 4).

In response, on the following day, March 23, the Office of the USTR initiated the dispute settlement procedures under the WTO and requested bilateral consultations with China as the first step. On April 3, the Office of the USTR announced a sanction plan that would impose additional tariffs of 25% on 1,300 items of products imported from China, including high-tech products, which are worth $50 billion. The following day, China responded by expressing its readiness to impose additional tariffs of 25% in retaliation on 106 items of products imported from the United States, including soybeans and automobiles. In light of the Chinese announcement, which he viewed as an unjustified retaliation, President Trump immediately ordered the Office of the USTR to consider imposing additional tariffs on $100 billion worth of imports of goods from China. In this way, the U.S.-China trade dispute escalated rapidly (Note 5).

The Office of the USTR's Section 301 investigation targeted at China is notable for the following three points.

First, it focuses exclusively on the technology field. This reflects the United States' concerns that its advantage in this field could be lost.

Second, the issues covered mostly concern the Chinese government's market-interventionist approach. The United States believes that the Chinese government's unjustified market intervention is weakening its advantage in the technology field.

Third, many of the issues pointed out in the Section 301 investigation report have no relation to existing binding international rules such as the WTO agreement. Concerning such issues, even if a trading partner's behavior does not violate international rules, investigation may be conducted if the United States concludes that the behavior is unreasonable or discriminatory or if it has undermined U.S. interests. However, if the United States imposes sanctions based on the results of the Section 301 investigation, this could in turn constitute a violation of international rules (Note 6).

Growing vigilance against the Made in China 2025 plan

Of the Chinese government's "unjustified market intervention," what keeps the United States vigilant is its industrial policy, particularly the "Made in China 2025" plan announced in 2015 (Note 7). Specifically, the American Chamber of Commerce in China criticized the implementation of Made in China 2025 as follows in a report published in March 2017 (Note 8).

Unlike other countries' plans to develop manufacturing industries, such as German Industry 4.0, Made in China 2025 is intended to promote Chinese companies' research and development (R&D) capabilities by providing them with preferential access to capital and to enhance their competitiveness by introducing technology from abroad. In concert with the 13th Five-Year Plan, the Internet Plus Action Plan, and other state-led development plans, Made in China 2025 constitutes a broad strategy to use state resources to establish comparative advantage for China in the manufacturing sector on a global scale. Regarding the implementation of Made in China 2025, it is necessary to keep a watchful eye over the following three aspects in particular:

(1) Reinforcing government control

Contrary to the principle of giving the market a decisive role in the allocation of resources, which was determined at the Third Plenum of the 18th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China held in November 2013, Made in China 2025 reaffirms the government's central role in economic planning.

(2) Intensifying preferential policies and financial support

Made in China 2025 illustrates the Chinese government's intent to leverage China's legal and regulatory systems to favor Chinese companies over foreign ones in targeted sectors. Moreover, industries targeted by Made in China 2025 will likely receive hundreds of billions of yuan in government support over the coming years. That could distort Chinese domestic and global markets. Such support may be used not only to invest in local innovation but also to fund foreign technology acquisitions. State-backed support for acquisition of specific technologies represents a new feature and natural extension of China's industrial policy.

(3) Setting global benchmarks

Made in China 2025 represents the latest far-reaching industrial policy on a continuum of such policies to develop not only national champions but also global champions. Policies documents related to Made in China 2025 set global sales growth and market share targets that are to be filled by "domestic products."

The policies incorporated in Made in China 2025 will have an impact not only domestically but also in other countries. Made in China 2025 aims to leverage the power of the state to alter competitive dynamics in global markets in industries core to economic competitiveness. However, Made in China 2025 risks generating market inefficiencies and sparking overcapacity on a global scale, according to the report.

These accusations are also included in the Section 301 investigation report that was mentioned earlier. In addition, in a statement issued when the list of products subject to additional tariffs on imports from China was announced on April 3, 2018, the USTR made clear that the list was targeted at products benefiting from policies that aim to promote the manufacturing sector, including Made in China 2025.

Strengthening of U.S. restrictions on Chinese companies' investment

The United States has become strongly vigilant against Chinese companies acquiring cutting-edge technologies through direct investments in the United States, including mergers and acquisitions (M&A). In response, the government is strengthening the national security review system concerning investments by foreign companies.

In the United States, an inter-agency committee called the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) is charged with the task of monitoring foreign direct investments based on the Foreign Investment and National Security Act of 2007 (FINSA). CFIUS is empowered by law to review national security risks that may arise from M&A through which foreign companies aim to acquire control over U.S. companies. If it judges that foreign investment in a U.S. company is posing a threat to the national security of the United States, CFIUS recommends "mitigation measures" that, if not accepted, could lead to withdrawal of the application.

FINSA, which was enacted in 2007, is a modified version of the Exon-Florio Provision of the Omnibus Foreign Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988. On the basis of FINSA, CFIUS's guidance concerning national security review (presented in Federal Register, December 8, 2008) cites 11 items as factors that should be taken into consideration in national security review. Among them, Items (1) to (5) have been carried over from the Exon-Florio Provision, while the other items have been adopted under FINSA (Table 1).

| (1) The potential effects of the transaction on the domestic production needed for projected national defense requirements. |

| (2) The potential effects of the transaction on the capability and capacity of domestic industries to meet national defense requirements, including the availability of human resources, products, technology, materials, and other supplies and services. |

| (3) The potential effects of a foreign person's control of domestic industries and commercial activity on the capability and capacity of the United States to meet the requirements of national security. |

| (4) The potential effects of the transaction on the sales of military goods, equipment, or technology to countries that present concerns related to terrorism; missile proliferation; chemical, biological, or nuclear weapons proliferation; or regional military threats. |

| (5) The potential effects of the transaction on U.S. international technological leadership in areas affecting U.S. national security. |

| (6) The potential national security-related effects of the transaction on U.S. critical infrastructure, including major energy assets. |

| (7) The potential national security-related effects on U.S. critical technologies. |

| (8) Whether the transaction could result in the control of a U.S. business by a foreign government. |

| (9) The relevant foreign country's record of adherence to nonproliferation control regimes and record of cooperating with U.S. counterterrorism efforts. |

| (10) The potential effects on the long-term projection of U.S. requirements for sources of energy and other critical resources and material. |

| (11) Other factors which the president and CFIUS believe should be taken into consideration |

| Source: Created by the author based on Department of Treasury, Office of Investment Security, "Guidance Concerning the National Security Review Conducted by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States," Federal Register, Vol. 73, No. 236, December 8, 2008. |

In November 2017, the bill for the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act of 2017 (FIRRMA), which is intended to strengthen CFIUS's powers, was tabled in the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. This bill includes provisions that would expand the scope of investment transactions subject to review to include the following areas, and provides an explicit legal basis for practices that have until now been employed based on implicit rules.

(1) Non-passive investment in critical technology companies and critical infrastructure in the United States

The definition of passive investment under the bill is narrow and does not include transactions in which foreign investors are members of the board of directors (including in the capacity of observers) or transactions through which foreign investors gain access to non-public information. As a result, the scope of non-passive investments subject to national security review expands all the more.

(2) Transactions involving technology transfer from critical technology companies in the United States

The scope of transactions subject to review covers not only cases of technology transfer that may occur through foreign-led M&A targeting U.S. companies but also cases of technology transfer through joint ventures between U.S. and foreign companies and licensing deals, which are not subject to review under the current system.

(3) Transactions concerning cybersecurity and information security

The scope of transactions subject to review cover cases that could lead to leakage of sensitive data and personal information concerning U.S. citizens that could affect national security in addition to cases that could threaten cybersecurity in the United States.

(4) Purchase or lease by foreign companies of real estate assets in locations adjacent to military installations and sensitive facilities in the United States.

Although FIRRMA does not explicitly use language that indicates China as a target, Senator John Cornyn and Congressman Robert Pittenger, who tabled the bill in the Senate and the House, respectively, emphasized the threat from China as follows when explaining the necessity of the law.

"By exploiting gaps in the existing CFIUS review process, potential adversaries, such as China, have been effectively degrading our country's military technological edge by acquiring, and otherwise investing in, U.S. companies (Note 9)."

"China is buying American companies at a breathtaking pace. While some are legitimate business investments, many others are part of a backdoor effort to compromise U.S. national security (Note 10)."

Indeed, "critical technology companies" include companies owning emerging technologies necessary for the United States to maintain or acquire a technological advantage over "countries of special concern" that are regarded as national security threats. China is highly likely to be classified as a "country of special concern (Note 11)."

The criteria added under FIRRMA are not applied to all trading partner countries. Trading partner countries that satisfy certain conditions, such as countries which have concluded joint defense agreements with the United States (countries on the "white list" compiled by CFIUS), are granted exemption. As a result, companies from China, which is expected to be excluded from the white list, are likely to receive discriminatory treatment compared with companies from U.S. ally countries.

Recent cases of dispute over technology between the United States and China

Even before the enactment of FIRRMA, Chinese companies are already finding it difficult to acquire cutting-edge technologies from the United States through M&A. In 2013-2015, China was the most frequent target of national security review among the countries investing in the United States, with 74 cases of acquisition by Chinese companies subjected to review between 2013 and 2015. Of those cases, 39 (52.7%) were in the manufacturing sector (Table 2). Of foreign companies' acquisition plans that have been abandoned due to failure to obtain approval from CFIUS since the inauguration of the Trump administration, Chinese companies accounted for the largest number by nationality (Table 3). Among the abandoned acquisition plans, Canyon Bridge's plan to acquire Lattice Semiconductor and Ant Financial's plan to acquire MoneyGram International are typical cases (Note 12).

| Country | Manufacturing | Finance, Information, and Services | Mining, Utilities, and Construction | Wholesale Trade, Retail Trade, and Transportation | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 39 | 15 | 13 | 7 | 74 |

| Canada | 9 | 9 | 19 | 12 | 49 |

| UK | 25 | 15 | 3 | 4 | 47 |

| Japan | 20 | 12 | 5 | 4 | 41 |

| France | 8 | 9 | 1 | 3 | 21 |

| Germany | 9 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 14 |

| Netherlands | 4 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 14 |

| Singapore | 3 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 12 |

| Switzerland | 10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 12 |

| Total (including other countries) | 172 | 112 | 66 | 37 | 387 |

| Source: Created by the author based on Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, "Annual Report to Congress" (Reported Period: CY 2015). | |||||

| Target | Would-be acquirer | Country | When killed | Deal size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qualcomm | Broadcom | Singapore | Mar-2018 | $117 billion |

| Xcerra | Hubei Xinyan Equity Investment Partnership | China | Feb-2018 | $580 million |

| MoneyGram International | Ant Financial Services Group | China | Jan-2018 | $1.2 billion |

| Cowen | China Energy Company Limited | China | Nov-2017 | $100 million |

| Aleris | Zhongwang USA | China | Nov-2017 | $1.1 billion |

| HERE | NavInfo | China | Sep-2017 | $330 million |

| Lattice Semiconductor | Canyon Bridge Capital Partners | China | Sep-2017 | $1.3 billion |

| Global Eagle Entertainment | HNA Group | China | Jul-2017 | $416 million |

| Novatel Wireless | T.C.L. Industries Holdings (Hong Kong) | China | Jun-2017 | $50 million |

| Cree | Infineon Technologies | Germany | Feb-2017 | $850 million |

| Source: Created by the author based on David McLaughlin and Kristy Westgard, "All about CFIUS, Trump's Watchdog on China Dealmaking: Quick Take," Bloomberg, April 20, 2018. | ||||

1) Canyon Bridge's plan to acquire Lattice Semiconductor

In September 2017, based on the recommendation of CFIUS, President Trump issued an order blocking the acquisition of Lattice Semiconductor, a U.S. semiconductor manufacturer, by Canyon Bridge, an investment fund backed by the Chinese government. In addition to designing semiconductors used in mobile terminals, including smartphones, automobiles, medical devices, and telecommunications equipment, Lattice also develops devices for military use. In a statement, Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin explained that the national security risk posed by the transaction relates to the potential transfer of intellectual property to the foreign acquirer, the Chinese government's role in supporting this transaction, the importance of semiconductor supply chain integrity to the U.S. government, and the use of Lattice products by the U.S. government (Note 13).

2) Ant Financial's plan to acquire MoneyGram International

Ant Financial is a financial services company affiliated to the Alibaba group and is mainly responsible for operating the Chinese e-commerce giant's payment system. MoneyGram International of the United States, headquartered in Dallas, provides international money transfer service. In April 2017, Ant Financial agreed with MoneyGram on an acquisition plan worth $1.2 billion, beating competition from Euronet Worldwide, a U.S. e-payment company. However, as the plan was not approved by CFIUS, Ant Financial and MoneyGram announced on January 2, 2018 that they had to abandon the deal. Reuters, quoting an informed source, reported that the companies were unable to obtain approval from CFIUS probably because concerns over the handling of personal information could not be eliminated (Note 14). In the future, investments by foreign companies in financial services companies handling personal data will become a major focus of national security review by CFIUS.

Accelerating the opening up to the outside and shedding dependence on the United States is necessary

Under strong pressure from the United States, China is making efforts to further open itself to the outside world despite taking actions to push against the U.S. pressure. Specifically, in a keynote speech at the opening of the 2018 Boao Forum for Asia Annual Conference, Chinese President Xi Jinping vowed that China will take the following four policy measures in order to further open itself to the outside: (1) significantly broadening market access; (2) creating a more attractive investment environment; (3) strengthening protection of intellectual property rights; and (4) taking the initiative to expand imports (Table 4). These policy measures are intended to increase foreign direct investments in China through improvement of the investment environment in addition to easing the economic dispute with the United States.

| (1) Significantly broaden market access |

|---|

| In the services sector, financial services in particular, China must accelerate the opening up of the insurance industry, ease restrictions on the establishment of foreign financial institutions in China, expand their business scope, and open up more areas of cooperation between Chinese and foreign financial markets. In the manufacturing sector, restrictions remain mostly in a small number of industries, such as automobiles, ships, and aircraft. Now these industries are basically ready to open up. As the next step, China must ease foreign equity restrictions in these industries as soon as possible, automobiles in particular. |

| (2) Create a more attractive investment environment |

| China will enhance alignment with international economic and trading rules, increase transparency, strengthen property rights protection, uphold the rule of law, encourage competition, and oppose monopoly. In March 2018, China established new agencies such as the State Administration for Market Regulation as part of a major readjustment of government institutions, thereby removing the systematic and institutional obstacles that prevent the market from playing a decisive role in resources allocation and enable the government to better play its role. In the first six months of 2018, China will finish the revision of the negative list on foreign investment and implement across the board the management system based on pre-establishment national treatment and negative list. |

| (3) Strengthen protection of intellectual property rights |

| In 2018, China is re-instituting the State Intellectual Property Office to step up law enforcement, significantly raise the cost for offenders, and fully unlock the deterrent effect of relevant laws. China protects the lawful intellectual property rights owned by foreign enterprises. |

| (4) Take the initiative to expand imports |

| In 2018, China will significantly lower the import tariffs for automobiles and reduce import tariffs for some other products. China will import more products that are distinctive and superior. China will seek faster progress toward joining the WTO Government Procurement Agreement. In November 2018, China will hold the first China International Import Expo in Shanghai. |

| Source: Created by the author based on "Openness for Greater Prosperity, Innovation for a Better Future," a keynote speech delivered by President Xi Jinping at the opening ceremony of the 2018 Boao Forum for Asia Annual Conference" (April 10, 2018). |

At the same time, in order to reduce its dependence on the United States in the technology field, China should not only enhance indigenous R&D capability but also maintain good relationships with other developed nations such as Japan, Europe, and strengthen cooperative economic relationships, including technology transfer.

China and the United States have held three rounds of trade talks at the ministerial level since early May 2018, but the two sides have yet to reach any concrete agreement. With the confrontation likely to drag on for long, it has become all the more important for China to accelerate its opening up to the outside world and reduce its dependence on the United States.

The original text in Japanese was posted on June 4, 2018. This English version has been partly revised to take into account of the latest developments.