Japan’s new capitalism and mission-oriented industrial policy has been formulated to cope with changing global supply chains and to drive economic growth. The policy places emphasis on economic growth and income distribution but needs to address risks from China’s market transformation and climate change to succeed. Clear industrial targets for innovation must be based in high quality markets and on industrial inputs that are difficult to substitute. However, questions remain on how to interface with China in global trade and the degree to which government intervention may be necessary to combat climate change in sectors without current demand. Professor Richard Baldwin of Graduate Institute, Geneva, Makoto Yano, Chairman of RIETI, and Tetsuya Watanabe, Vice President of RIETI met online to discuss the current issues.

Tetsuya Watanabe:

Introduction

The supply chain disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic reminded us how integrated our supply chains are. It highlighted the supply chain risks for automakers in particular as the necessary procurement of automotive parts and components was disrupted. Furthermore, the disruption to supply chains revealed how little we know about our own global supply chains and their hidden risks, which have been impacted by pandemic and geopolitical tensions. Decarbonization of the global supply chain is also a priority for decision making of business leaders. Products and services are in the end being selected by consumers and citizens around the globe who have become very sensitive about the carbon footprint throughout the supply chain. Geopolitical tensions and the increased importance of addressing economic security concerns required us to take a coordinated approach among like-minded countries but at the same time we need to strengthen the rule-based global and regional economic order and upgrade the free trade system to avoid fragmentation of supply chains. Digital technologies change the supply chain dramatically and how governments and private sectors can transform themselves in the data age is a huge challenge in every country.

The NBER (National Bureau of Economic Research) working paper “Risks and Global Supply Chains: What We Know and What We Need to Know,” authored by one of our speakers, Professor Richard Baldwin, and Dr. Rebecca Freeman of the Bank of England, identifies the risks to and from global supply chains, how global supply chains have recovered from past shocks, and proposes a risk-versus-reward framework to evaluate whether risk policies are justified. Professor Baldwin and Dr. Freeman also discussed how exposures to foreign shocks are measured and considered the future of global supply chains in light of the current policy environment.

Heightened supply chain risk requires individual companies to respond to new risks by balancing the costs and risks of relying on global supply chains. But at the same time, the increasing uncertainty of global supply chains necessitates that governments also react to new risks and the challenges.

In this new environment, new thinking on capitalism emerged in Europe and the U.S. and elsewhere. And in Japan too, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida announced new capitalism as the main pillar of his economic policy. I first invite Chairman Yano to share his perspective on the new capitalism and mission-oriented industrial policy, then Professor Baldwin will share his perspective, followed by a discussion.

Makoto Yano:

The need for a New Capitalism

Recently, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has proposed what he calls new capitalism as the basis of his policy agenda. By doing so, he emphasizes the importance of income distribution.

His initiative advocates the creation of a “good loop” of economic growth and income distribution. That is, he aims to end wage stagnation and, by doing so, to revitalize the Japanese economy. Mr. Kishida advocates controlling large corporations’ dominant market power over smaller companies, from which they purchase intermediate goods and services at low prices, as is the traditional Japanese business style. I agree with the premise of this policy. The policy aims to expand middle income families and to increase population.

To realize this, the government is to subsidize education and housing and assist in childcare, for example, by increasing the number of nursery schools. This in particular has been noted as a problem because the small number of nursery schools is preventing women from both entering the workforce and remaining at work. Moreover, Prime Minister Kishida advocates increasing wages for essential workers, particularly those in nursing, elderly care, and childcare. This is partly because of the issues revealed during the current COVID-19 situation, but, of course, the need for wage increases in nursing services and elderly care was evident even before the pandemic.

Compared to the U.S., Japan's wages in nursing and elderly care are low. Recently, the BBC has reported that the Japanese average wage has been stagnant for over three decades, whereas wage rates have generally increased in many countries such as Germany, France, the UK, the U.S., and South Korea. However, this is partly a reflection of Japan’s GDP as a whole, which has also not seen much growth.

I think that the administration perceives that by raising wages, it will create additional economic progress and economic growth.

Past industrial policy and new targets

METI is now advocating a “moonshot.” This is a part of the new industrial policy, which aims to make policy more target-orientated, or you might say, mission-oriented. It differs from the old Japanese-style industrial policy, which set targets that had already been tested in more advanced economies at that time. Examples are electric appliances, cars and so on, the importance of which were obvious. This is in a sense similar to the current Chinese economic policies, although some of them are already more advanced than Japanese counterparts at this moment.

In the late 1980s, Japan switched from the old industrial policy to structural reform and is now thinking of adopting a new style of industrial policy, which aims at targets that are untested and unknown. When a country is trying to catch up to more advanced economies, it is not difficult to decide what sort of technologies it should adopt. Once an economy achieves the top technological level, however, it is very difficult to determine what technologies to focus on; at that point, the economy fall into a state of confusion. Falling into such a state of confusion is unfortunately nearly inevitable for any country that stands at the front line of technological development. For about three decades since the 1960s, the U.S. was in that state. For the last three decades, Japan has been in a similar state of confusion. For Japan to get out of this state, it is very important to seek a new approach to industrial policy, promoting the development of brand new technologies in the world; this is how the U.S. managed to get out of its technological stagnation, by developing new technologies that now lead the world’s industries, including spaceships, computers, and the internet. I believe that it is a very good time for METI to create new industrial policy seeking the development of new technologies in this drastically changing world.

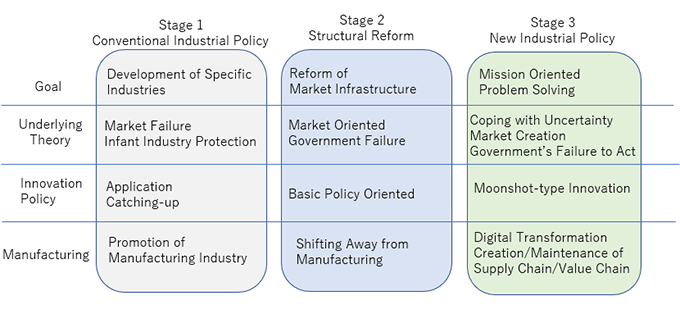

METI identified three stages of industrial policy since the 1950s. METI states that the goal of the first stage industrial policy was to develop specific industries, and the underlying economic theory was to deal with market failure or infant industry protection. The innovation policy was more focused on application and catching up to the developed countries’ models and manufacturing in the past, and the promotion of manufacturing was a very important part. And during the second-stage structural reform period, Japan wanted to reform the market infrastructure. METI wanted to make a market-oriented economic policy and to deal with the government failings, with an innovation policy focused on attaining more basic scientific knowledge.

Japan shifted away from manufacturing during the second stage, and I have thought that this was the correct approach. During this stage, unfortunately, Japan has weakened its technological edge for this period. I believe that this has prompted METI’s current initiative.

[Click to enlarge]

METI now wants to lead moonshot-type innovations. It wants to digitalize the industry as a whole and create or maintain new supply chains for the new digitalized economy. This new industrial policy is very similar to what Professor Richard Baldwin has emphasized during his past presentations at RIETI, discussing uncertainties of market creation, targeted innovation, digital transformation, and supply chain creation and maintenance. I agree with Professor Baldwin for the importance of pushing these issues. At the same time, however, there is a huge difference between where Japan is and where Europe and the U.S. are. The idea of this new industrial policy remains a broad concept in Japan, but its success is not guaranteed if Japan simply follows the U.S. or European models from the past or present.

The current targets being emphasized by the Japanese government are green technology, resiliency and sustainability, digital transformation, and income distribution. Currently, Japan wants to bring Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) to Japan and further their technology to develop logic chip production capabilities.

I believe that it is important to set up a grand design and philosophy that supports these initiatives. For instance, John F. Kennedy’s moonshot encompassed not just scientific knowledge but also commercial policy and targets, as well as military and national prestige. Clearly, market-oriented goal-setting was pursued during that period. It is also clear from the development of the Internet and computer technology that a clearly-defined, market-oriented vision of the unfolding of these networks was evident from the beginning stages of the development of these technologies. Before launching the new industrial policy, we need to develop this type of clear vision on how the policy will use technology and what should be developed to enable such a vision of the future.

Quality markets and industrial transfer

Society has seen great changes in technologies, such as with the adoption of personal computers, spaceships, smartphones, and e-commerce. The recent commercialization of space travel came as a real surprise to me. Behind such transformations, there are high quality markets, which are prerequisites for such developments. It is these well-organized, high-quality markets that laid the foundation for personal computers, spaceships, smartphones, and e-commerce, and that is what Japan lacks. This is in part due to the fact that what Japan is trying to develop is totally unknown, and it's unlike past transformations in industry. To develop such unknown technologies requires good markets. A market connects technologies to people’s lives. A market is a kind of dual-directional pipe where products go from technologies and resources to everyday life. Information or people's needs are connected through this pipe to technological development. Market quality can be seen as the quality of said pipe and the transfer of information through the pipe, given available technologies and consumer preferences. If the pipe is well developed, you can create a good loop between the production side and the consumption side of the economy. Currently, I believe that Japan does not have a good pipe connecting these two factors.

I think that the target of such a policy should be something that is difficult to achieve, like the moonshot or similar goals. It will take about 30 years from when the ideas for the technology are being developed until actual commercial use of such technologies. Space rockets for example took about 60 or 70 years to reach commercialization. To make commercial use of those advanced technologies, it is important to develop high-quality markets.

To make new technologies compatible to the market, I think that innovation must be needs-driven. Income distribution is particularly difficult to pinpoint as many and various opinions exist on the subject. Therefore, a good market is essential to achieving such targets. Japanese industrial policy is still a borrowed concept from Europe and the U.S. European economies went through reforms successfully in the 1980s and 1990s. They created very strong infrastructure which seeded new technologies that allowed them to become commercial leaders three decades later.

Richard Baldwin:

Macro goals and micro goals

I would like to begin by differentiating between macro goals and micro goals. The idea of inequality leading to stimulation of demand, which leads to stimulation and growth could be a macro goal. Nevertheless, on the micro side of new industrial policy, education, housing, and childcare all seem to be very clear in that they may boost productive capacity of an economy. For example, there is value for the country in having an educated society which is greater than the value for the individual. Therefore, education subsidies are a very good thing. Housing is another area where policy can have an impact, because housing stock moves more slowly than demand for housing. Moreover, childcare is another area where policy can be effectual because if the capacity for childcare were larger, or there was easier access to it, more women would utilize it and plan for that possibility.

There are, however, distinctions between the new economic policy and the former ones. I agree that the old industrial policy was, indeed, based on the need to ‘catch up,’ so to speak, and it was easier to visualize that Japan needed industry development in steel, automotive, electronics, cement, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, etc. In the 1980s, Europe and the U.S. were moving toward price-oriented policies and limited government. Japan followed suit with excellent growth. However, it became evident that catch-up growth and steady growth are not the same, eventually reducing the attractiveness of that policy option.

Responding to the rise of China

For the new industrial policy, areas where there are targets that industry cannot cope with by themselves would be key. Another factor that affects the situation is the rise of China. Its industrialization progressed at a rapid rate in the span of about two decades. During this industrialization, it imported from industrial intermediaries such as Japan, Germany, and the U.S. However, since around 2006, its trade-GDP ratio began declining as it imported less. It began substituting domestic production from its domestic industrial base in place of previously imported high-tech intermediates. Those previous exports to China are now fading, and it will not revert course because China’s trade-GDP ratio is converging to that of a large economy, like the U.S. or the EU. The implication of this is that the policy that worked for the last 20 years will no longer be effectual. Moreover, there are U.S.-China geostrategic tensions leading to industrial disruptions which have been driven by political factors. One example of this is the disruption in semiconductors. The sitting administrations in the U.S. and China will dictate how aggressive these tensions will become, but in the U.S., neither major political party is interested in a cooperative approach with China. In China, President Xi is focusing on internal markets and developing their industrial base. These changes have fundamentally ended the status quo that has existed for the last 20 years.

It is clear that there is a need to assess these trends; especially keeping an eye on what demand patterns for exports will evolve into in the face of diminishing demand from China. Companies surely have talented people working on what those targets should be, but it may require reorientation of production or concentration that would be better directed at the government policy level, so relevant targets necessarily incorporate this perspective. Policy targets must address areas where collective action is more effective than individual action in reorienting the economy as a whole.

Industrial response to climate change

The challenges of climate change, or as I like to call it, the climate rescue, are great. There will be a few decades in which to rescue ourselves from the damage that has been done and continues to be created. Actions for the mitigation of emissions and adaption to changes that are already happening will have serious implications for demand for manufacturing goods worldwide. This is a point that has already been made by many commentators. It is a very large transformation that many companies are undertaking. However, in some technologies, there are bottlenecks or coordination failures or externalities that can impact such transformation. One example of such a bottleneck is the adoption of electric vehicles. While policy makers can help prompt demand, companies like Tesla have solved the issue of adoption of electric vehicle technology by organizing the whole supply chain. However, electronic vehicles are relatively simple technology even compared to diesel or gasoline cars, and the supply chains are simple. Even for gasoline vehicles a moonshot was not necessary. However, it seems to me that hydrogen technology, carbon capture and other mitigating technologies require a more systematic push for development. The demand does not exist yet and so, here, government may be impactful. If such climate mitigating technologies do come to fruition it seems that only a small number of companies and countries will develop the technology, but it will need to be deployed everywhere in the world. This is a massive reorientation of demand for high-tech manufacturing, which is where the G7 countries are still global leaders. That being said, such technologies will have demand for decades into this century, even if only for domestic use.

Other areas of change will be adaption to extreme weather, including creation of sea walls, irrigation systems, moving cities, heat resistant agriculture, and so on. Precision irrigation and industrial agricultural equipment for planting that requires less water, less fertilizer, and less pesticides are other examples of super-high technology that will be in demand around the world during this period of rapid climate change. However, incentives for industry such as in agriculture may be required in Japan. Another area of adaptation of markets will be in water treatment and water production. Fresh water is already a critical issue for many regions, and desalination, water recycling and rain capture are examples of high-tech or medium-tech engineering and scientific solutions—the demand for which will also increase with climate change. It is clear that there is room for a micro-level industrial policy that might help avoid coordination problems and overcome certain externalities.

Potential targets

Determining appropriate targets for the new industrial policy is particularly difficult because industrial policy tends to be captured by industry. Industry has more knowledge about the technology in question than the government will ever be able to inform themselves about in a policy-relevant timeframe, but it may have differing incentives compared to other stakeholders, and so targets should be general but clear. Therefore, targets that address adapting to climate change and the changing manufacturing patterns in China are high-level enough that they should find significant public support and be implementable.

In terms of an intermediate timeframe, the rapid deterioration of the U.S.-China relationship and trade disruptive policies do justify industrial policies that safeguard key components. The idea of certain sectors that are critical to many surrounding sectors is something that policy should embrace again. The first criterion for this determination is the question of how complementary these inputs are to other industrial inputs. In the 1950s, Europe focused on coal and steel, forming trade communities for better coordination. Later, atomic energy was added, and these sectors became linchpins for other sectors. Semiconductors are similar in that regard, and this has been made clear during recent supply chain disruptions. For instance, it was not common knowledge that the automotive industry would be so heavily impacted by supply chain disruption in semiconductors. The inability to substitute such an input is another key criterion in determining an appropriate target, which, in turn, is also related to how difficult or time-consuming it may be to establish a similar infrastructure if the supply is lost. Here again, semiconductors are a good example. Taiwan has facilities at an advanced technical level that others may find challenging to replicate. In the medium term, as Japan, Europe, and the U.S. pivot to semiconductors, there may be a surplus of supply, leading some to characterize the current shift as a mistake. However, the degree to which they are necessary seems to outweigh any such criticism. The importance of securing domestic supply is now clear. Another industry that may face overcorrection, due to COVID-19, is the production of medical equipment and vaccine production. This may lead to waste but likewise it may be important to secure domestic infrastructures and supply.

Discussion

The role of government in target industries

Yano:

You mentioned that industrial experts are more knowledgeable than the government in technology. However, you also mentioned the large role that government could have in an industry such as the semiconductors. What is your take on these two positions?

Baldwin:

In my understanding, there is a part of the production in industry that is very cyclical where a new product, such as a memory chip, is designed: it starts as very expensive, but it becomes cheaper as production techniques are improved. Then more chips hit the market. This is an undersupply and oversupply situation. We are seeing a situation like this currently where the private industry is reluctant to invest due to this cyclical supply-demand structure, so government policy could be a kind of insurance to keep production going even when it may not be so profitable. Other industries such as education and healthcare also involve a government element because some parts of these industries are not profitable enough for private industry to maintain interest, despite societal demand for them.

So, such a target industry would have a lack of substitutable inputs, very long lead times, and a cyclical nature. These elements would make it difficult for the industry to cover all costs. It is in situations like this that I think that if there are very clear reasons for public investment, there could be public and private return from such investment.

In Europe, Airbus was one such case. Airbus could not enter the market as a private company because Boeing and McDonnell Douglas were already producing jets: a private company could not justify the risks involved in such a massive investment. I think that this public-private wedge that was used for Airbus can similarly be a justification for investment in semiconductors.

Yano:

Currently, in the semiconductor industry, Intel is completely private however the Taiwan authority is involved in TSMC and this involvement has led to a different form of industry. TSMC has accumulated technologies and development over time which are more diverse than other players. What is it particularly about semiconductors that means that the private sector cannot catch up by themselves?

Baldwin:

Here we are talking about getting a new production site or a new company producing the good. In some cases, this may require continued support but in other cases it may not. Airbus is now a profitable company and does not require support. Intel is also a profitable company, but it grew during the personal computer boom and was entangled with the growth of the Windows operating system. There are many products that were designed around—and in cooperation with—these chips, so the technology is self-sustaining at this point. It seems the Korean and Taiwanese semiconductor industries were influenced by government policy at one point but perhaps do not need it now. However, as I understand it, Japan is interested in manufacturing chips that do not currently exist, and for this, massive support from the government will be needed over many years. There is more of a need to establish the industry domestically, specifically due to U.S.-China tension, which has made trade between these states no longer free or guaranteed.

I understand and agree with your suggestion that permanent subsidization should only be used in extraordinary cases. Healthcare, education, roads, judiciary, police, fire brigades are all examples of areas that require permanent subsidies because of the gap between public and private. In other cases, there should be termination clauses if subsidization of an industry is going to work, that are based upon the evaluation of costs and benefits for society. So, it is also important to distinguish between startup help and permanent help.

There was also a case in the U.S. where massive government support was given to a semiconductor company to establish a cutting-edge manufacturing base, but eventually only a warehouse was built in Wisconsin. So private companies must also be forced to uphold agreements that they make. It is not just a case of injecting funds.

Watanabe:

You mentioned that coordination in some cases may justify government industrial policy intervention regarding the rise of China and climate change issues. You also mentioned the need for the coordination among the like-minded countries. Could you explain what you mean by increased coordination that may be necessary, due to the changes in demand resulting from China’s new trade balance?

Baldwin:

The argument is for requiring least amount of government intervention. One example is evident in trains, heavy earth moving equipment, or big, advanced cranes and construction equipment etc. that were being imported from Japan, Germany, or the U.S. when China was in its fast industrialization phase, say from 1990s to 2010. The demand for all this equipment coming in was large enough to distort the world market. However, now, for example, China has their own construction equipment produced locally, so the demand for high-tech capital goods and high-tech intermediate inputs is moving. Maybe industry can adapt fast enough to this change, but there is a real possibility that this change is large and systemic. So, there may be a need for coordination among G7 manufacturers to realize that the Chinese market is not coming back and is orienting itself towards other areas. It may well be that the private sector has sufficient incentives to do that. However, the manufacturing of this equipment takes many companies—and perhaps the government could help in coordination of the supply chain between nations, and so on. However, the changing patterns for sophisticated and manufactured goods are nowhere near as strong as the shifting patterns for semiconductors.

Use of nuclear energy in achieving decarbonization goals

Yano:

Regarding the considerations on nuclear energy, France and the European Union announced that nuclear is one way of coping with global warming and that nuclear will remain in the picture. What is your opinion on this technology?

Baldwin:

In the German case, the then Chancellor, Angela Merkel decided to phase out all nuclear energy after the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami. I understand the concern for nuclear waste in the long term. However, there does not seem to be enough time to change to other sustainable technology. Nuclear energy is very low carbon and although it brings other problems and vulnerabilities, there may not be enough time before 2030 or 2050 to control carbon emissions without it. It may be the lesser of two evils right now. For Japan, however, is a different case because it is geologically active, so the seismic activity might make it less attractive as an option. France, on the other hand, has been using nuclear power for a long time which has helped them adjust to climate goals. I think, in terms of combating climate change, we should use all of the tools that we have. Nuclear (energy) is a tool which has a long-run costs but short-run benefits.

Ensuring the interface with state capitalism

Yano:

Some say that China is no longer a viable trading partner for the U.S., Europe, and Japan. Is that your view as well?

Baldwin:

I would not take that view. That being said, I think that China’s trading pattern is changing to that of a normal, mega-economy but that this change is not widely understood to be part of a permanent transition. The new equilibrium that we have arrived at will remain. The problem is the interface between China's type of capitalism and others, such as the capitalism in Europe, Japan, and the U.S. Over time, Europe, Japan, and the U.S. have come to terms with certain ways of interfacing with each other. Europe has a different capitalist system than the U.S. including the preventative principle, regulation, and social goals. Furthermore, Japan and the U.S. faced a great deal of conflict during the late 1980s and early 1990s until an interface was worked out. We must now find an appropriate interface for China. They will not change, and we will not change. I am optimistic that we will find an interface that works because there is so much money to be made in finding it; it could be so disruptive. China produces intermediate inputs that are used widely in manufactured goods, and these are pervasive throughout the world’s value chains, to a degree that most people still do not comprehend. Therefore, if you buy a good from Canada, the EU, etc., many inputs are likely made in China. So, it will be very expensive and difficult to separate Chinese manufacturing especially for intermediate inputs, and there will be an imperative to find a way to cooperate. A main issue is with industrial subsidies.

One example of such cooperation is the U.S. and European aircraft industry, with military interest on U.S. side and Airbus on the other. To clarify, China is undergoing permanent change led by one administration, and this is not a transitory action. China has become like Germany, a manufacturing powerhouse exporting and making industrial parts themselves. In the medium term, U.S.-China tensions make reliance on China risky, and this type of risk is difficult to plan for, due to the escalations that are possible in such a situation. An example of this risky nature is the reactions during the Trump administration leading to heightened tensions.

Yano:

While the U.S.-Japan relationship had tensions during the 1980s, one factor that is different with China is the size of its economy. Japan is smaller than the U.S. in every way. China, on the other hand, is huge, both in terms of population, land, and market potential. It is entangling political and economic powers at the same time. This is a new model for U.S., Europe, and Japan to cope with. China’s population is far larger than the U.S., Europe and Japan combined, and they may become even more powerful.

Baldwin:

It is never possible to separate economics from politics at that level. China has been successful at industrializing and has driven some U.S. industries out of business. However, U.S. industry as a whole is not suffering in terms of production or exports. It is adapting. The domestic market effects are leading to popular backlash against China. There are also political exploitations of the tensions to get votes. However, it may not be possible to separate these elements. Solving the issue of the integration of China into the world system is a difficult problem that I cannot address. However, we should deal with elements such as forced technological transfers, subsidies, and the purchase of overseas companies. These elements are leading to changes in competitiveness at a product and firm level which are viewed as unfair. For instance, in commercial aircraft there was an agreement between the U.S. and Europe about how much financing could be given. This resulted in a series of industrial sector-level agreements and subsidy practices. Thus, there is a set of practical things that can be done on a commercial level that can solve some problems. It may be difficult to say if this will solve the larger problems, but they are not really for economist to solve.

These issues are bilateral or plurilateral issues and not within the purview of the WTO, so they will have to be addressed as such. So, my suggestion would be for METI and other economists to focus on allegations of unfair trade and commercial tensions. These kinds of discussions occur regularly between Europe, Japan, Korea, and the U.S., but the way those subsidies and policies work in China is different. The old tools like countervailing duties may not be sufficient, so that is where we should focus the dealings.

Watanabe:

Richard touched upon a very important point by focusing on the need of interface with the state capitalism. Of course, we need to address economic security concerns and take a coordinated approach among the like-minded countries, but at the same time our economies are so interdependent that we cannot decouple the global economy. In this regard, we have to bridge the different types of capitalisms and create an interface with their state capitalism. We have some tools in our toolbox already such as rules on industrial subsidies, government procurement, etc. By upgrading these toolkits, we can upgrade and strengthen the free trading system and rule-based global and regional economic order. That is the very important point we should not lose sight of and that is where Japan and other middle-power countries caught in the middle of the superpower competition should play a role. Thank you.