| Author Name | Willem THORBECKE (Senior Fellow, RIETI) |

|---|---|

| Creation Date/NO. | September 2025 |

| Download / Links |

This Non Technical Summary does not constitute part of the above-captioned Discussion Paper but has been prepared for the purpose of providing a bold outline of the paper, based on findings from the analysis for the paper and focusing primarily on their implications for policy. For details of the analysis, read the captioned Discussion Paper. Views expressed in this Non Technical Summary are solely those of the individual author(s), and do not necessarily represent the views of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI).

Many shocks have buffeted the Japanese economy since 2012. The monetary base increased fourfold between 2013 and 2024 as the Bank of Japan pursued its two percent inflation target. The yen, after appreciating 40% against the U.S. dollar between June 2007 and December 2012, depreciated 60% between the beginning of 2013 and the end of 2024. World demand has fluctuated with rising tariffs, the COVID-19 pandemic, and other external events. Dubai crude oil prices fell from $108 in January 2013 to $28 in January 2016 and then rebounded to $112 in January 2022.

This paper investigates how these and other shocks affect Japanese sectoral stock prices. Investigating how economic news impacts share prices can shed light on how it affects the broader economy. In theory stock prices equal the expected present value of future cash flows. Factors that increase sectoral stock returns portend higher sectoral earnings. As Black (1987, p. 113) noted, “The sector-by-sector behavior of stocks is useful in predicting sector-by-sector changes in output, profits, or investment. When stocks in a given sector go up, more often than not that sector will show a rise in sales, earnings, and outlays for plant and equipment.”

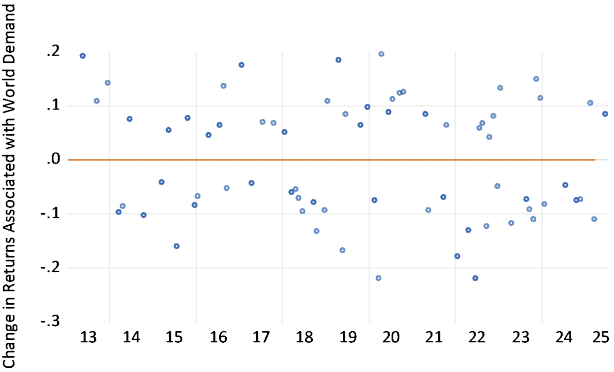

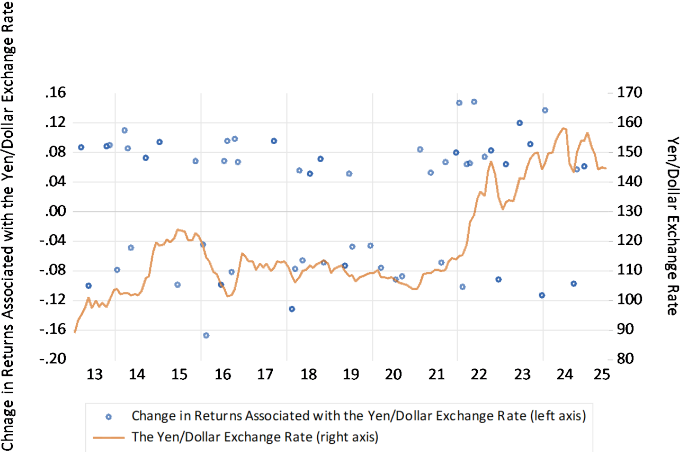

The evidence indicates that world demand and the value of the yen are especially important for the Japanese economy. All 86 sectors investigated have statistically significant exposures to these two variable. In addition, Figure 1A shows that in almost half of the months investigated between 2013 and 2025, investors reacted to expectations of changes in world demand. Figure 1B shows that in 37% of the months investigated, they reacted to expectations of changes in the yen/dollar exchange rate. News of changes in world demand and the yen/dollar exchange rate frequently drove fluctuations in the aggregate Japanese stock market of greater than 10% in a single month. These findings indicate that the international economy is vital for the Japanese economy.

Japanese firms occupy key niches in global value chains. For instance, Murata makes ceramic capacitors, Sony makes image sensors, Shimano makes bicycle parts, and JSW makes nuclear reactor parts. These specialized products are crucial to many global industries.

It is essential for the Japanese economy to maintain technological advantages in these niches. Technological competition with Asian neighbors is fierce. The Japanese government should make sure know-how is not pilfered nor that it inadvertently falls into competitors’ hands.

Since Japanese firms play such a vital role in the world economy, their interest in unencumbered trade is immense. The Trump Administration is engaged in a tariff war, but the protectionist pressures have been building for decades. Rather than only undertaking transactional exchanges with the U.S., Japan should engage with the U.S. and other countries to address the causes of global imbalances. High on the list should be encouraging the U.S. to reduce its budget deficit.

In addition, the Japanese government should seek as much as possible to maintain free trade with countries other than the U.S. Protectionism is contagious, and Japan and other countries suffering from U.S. tariffs should strive to maintain open markets with each other.

The Japanese government should also help firms through export promotion activities. For instance, Makioka (2021) found that government support for firms to attend trade fairs led to significant increases in exports. Much of this increase was along the extensive margin. He also reported that the impact was far larger for trade fairs outside of Asia. Thus the government should help firms to not only penetrate markets that are close by but also to enter new markets that are far away.

Finally, given uncertainties in the global economy, any steps that would help firms to supply to the domestic market would be desirable. This could include sponsoring research and development for products that can help with the demographic transition. One example is medical devices that treat Alzheimer’s disease. Another example is robots that could replace workers in manufacturing and services. As Japan’s population ages, there will be many needs for products that cater to aging citizens and that mitigate worker shortages.

- Reference(s)

-

- Black, F. 1987. Business Cycles and Equilibrium. New York: Basil Blackwell.

- Krippner, Leo. 2013. Measuring the Stance of Monetary Policy in Zero Lower Bound Environments. Economics Letters 118, 135–138.

- Makioka, R. 2021. The Impact of Export Promotion with Matchmaking on Exports and Service Outsourcing. Review of International Economics 29, 1418-1450.