| Author Name | KITAO Sagiri (Senior Fellow (Specially Appointed), RIETI) / NAKAKUNI Kanato (University of Tokyo) |

|---|---|

| Download / Links |

This Non Technical Summary does not constitute part of the above-captioned Discussion Paper but has been prepared for the purpose of providing a bold outline of the paper, based on findings from the analysis for the paper and focusing primarily on their implications for policy. For details of the analysis, read the captioned Discussion Paper. Views expressed in this Non Technical Summary are solely those of the individual author(s), and do not necessarily represent the views of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI).

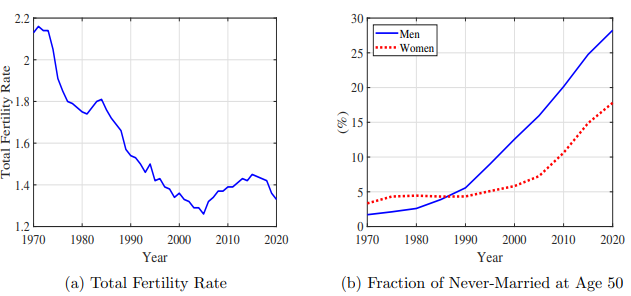

Over the past half century, the nature of the Japanese family has undergone substantial changes. In addition to structural changes including the secular decline in marriage and fertility rates shown in Figure 1, we must not disregard the changes in time allocation within households (particularly among women). For example, married women now spend more time on leisure and childcare than 50 years ago, and significantly less time on housework.

What are the factors that shape this long-term trend in the nature of the family? When considering long-term trends over the past half century, we cannot ignore the role played by the technological development that forms the foundation for our social and economic activity, and the resulting shift in wage structure. These key factors shape Japan’s income levels and the way that income is distributed, influencing people’s decisions and behavior, including family formation and time allocation.

Technological progress is not a simple one-dimensional object. Its forms and implications are heterogeneous, and not all workers are in a position to benefit from it equally. For example, technological progress of the kind that results in a broad-based improvement in workers’ productivity and wages—a rise in total factor productivity (TFP)—is a concept often used in macroeconomics to understand changes in the level of technology. There are other kinds of technological progress, such as skill-biased technological change (SBTC)—the development of AI technology, for example—which contributes to increasing the productivity and wages of high-skilled workers who can utilize this technology better. Other important kinds of technological progress include gender-biased technological change (GBTC) and female specific skill-biased technological change (F-SBTC), which boost women’s productivity and wages relative to men’s. They have contributed to the contraction in the gender pay gap observed over the past few decades in Japan and overseas. Various factors such as the rise of service industries in which women represent a higher fraction of the labor force, and the aging population and the growth of health care, welfare, nursing, and other services, have influenced these technological changes.

In this research, we began by using long-term time-series data on wages and labor supply in Japan, grouped by gender and educational background, to estimate the degree of each kind of technological development described above (the rise in 1. TFP, 2. SBTC, 3. GBTC, and 4. F-SBTC) over the past half century. We then undertook a quantitative analysis of the roles performed by each kind of technological progress in explaining long-term trends related to fertility and marriage rates, women’s time allocation, children’s education, and other aspects of families’ behavior.

The main findings of this research are described below. To begin with, we found that technological progress that contributes to an increase in women’s productivity and wages (GBTC and F-SBTC) has significantly influenced trends related to family formation including the decline in fertility and marriage rates. According to our calculations, GBTC and F-SBTC exhibited annual growth rates of 0.55% and 1.52%, respectively, from 1970 to 2020. If this technological progress had not occurred, and these technologies had remained unchanged at 1970 levels, we found that the marriage rate in 2020 would be approximately 10 percentage points higher than the baseline in each case. This means that GBTC and F-SBTC explain approximately 70% of the decline in the marriage rate in Japan over the past 50 years. Likewise, the total fertility rate as of 2020 would be 0.3 to 0.4 percentage points higher if there had been no growth in GBTC and F-SBTC, meaning that GBTC and F-SBTC explain approximately 40% of the decline in the total fertility rate over the past 50 years. We highlight two implications of GBTC and F-SBTC to interpret these results. First, the (relative) rise in women’s wages has increased the opportunity costs of having children and spending time on childcare. Second, women’s higher earning ability has diminished the economic attractiveness of marriage. Our findings suggest that GBTC and F-SBTC contribute significantly to the decline in fertility and marriage rates through these channels.

We found that the growth in TFP and SBTC plays a significant role in shaping trends related to women’s time allocation, specifically the increase in leisure time and the decrease in work hours. (Whereas women’s labor participation rate has been on the rise for the past few decades, the average number of hours worked has been declining.) TFP and SBTC exhibited annual growth rates of 0.22% and 0.41%, respectively, from 1970 to 2020. We found that if none of this technological progress had occurred, the working hours of married women in 2020 would be approximately 9% longer than the baseline, and 9–12% less time would be allocated to leisure. The TFP growth increases the productivity and wages of all types of workers, regardless of educational background and gender, while SBTC raises the wages of all high-skilled workers regardless of gender. This technological progress boosts household income, enabling people to work fewer hours and enjoy more leisure time while maintaining the same level of consumption. Our findings suggest that SBTC and TFP growth have shaped the trend toward less working time and more leisure for married women through this income effect.

We have shown that trends in family behavior such as marriage and childbirth and time allocation within the households are affected by a combination of multiple factors that progress over time. These include various kinds of technological progress, changes in industrial and wage structures, and rising levels of education. When considering government policies related to family behavior, such as measures to combat the declining birth rate and to raise female labor participation, it is important to understand not only short-term trends in economic variables but also the current situation through the analysis of medium- and long-term data. This will enable us to establish realistic goals and to implement sustainable policies.