| Author Name | TAKAHASHI Ryo (Waseda University) / IGEI Kengo (Keio University) / TSUGAWA Yusuke (UCLA) / NAKAMURO Makiko (Faculty Fellow, RIETI) |

|---|---|

| Research Project | Implementing Evidence-Based Policy Making in Japan |

| Download / Links |

This Non Technical Summary does not constitute part of the above-captioned Discussion Paper but has been prepared for the purpose of providing a bold outline of the paper, based on findings from the analysis for the paper and focusing primarily on their implications for policy. For details of the analysis, read the captioned Discussion Paper. Views expressed in this Non Technical Summary are solely those of the individual author(s), and do not necessarily represent the views of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI).

The COVID-19 has become one of the deadliest communicable diseases of the 21st century, causing approximately seven million deaths globally as of the time of this writing. Until effective vaccines were developed, measures such as social distancing, wearing face masks, and restricting travel constituted the main infection countermeasures. In Japan, the government closed all elementary, junior high, and high schools from February to May 2020. After schools reopened, it encouraged children to avoid talking while eating lunch at school to prevent the risk of COVID-19 outbreaks, a policy known as silent eating (mokushoku in Japanese). Silent eating was implemented until November 2022, when the recommendation was removed from the Novel Coronavirus Response Headquarters’ “Basic Policies for Novel Coronavirus Disease Control.”

Despite the implementation of silent eating for over two and a half years, no study to date has examined its effectiveness in reducing the risk of COVID-19 outbreaks. Meanwhile, concerns have been raised regarding the potentially negative effects of the policy on children’s well-being and educational attainment. The purpose of this research is to examine the impact of silent eating on the risk of COVID-19 outbreaks and provide scientific evidence regarding its effectiveness. In November 2022, the Japanese government decided not to require children to eat their school lunches in silence, and some public schools revised their silent eating rules in response. Using this revision of the silent eating requirement as a natural experiment, we investigated the effect of silent eating on class closures in public schools.

We analyzed data from public elementary and junior high schools in Chiba Prefecture from November 1, 2022, to February 28, 2023. During this period, on November 29, 2022, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) notified boards of education across Japan that, subject to the implementation of necessary measures, it would no longer require silent eating at schools. On December 22, 2022, the government of Chiba Prefecture requested each local government board of education within the prefecture to revise silent eating rules, noting that such a revision was appropriate from the perspective of educational considerations. Our data was composed of (1) data from the survey conducted by Chiba Prefecture’s board of education in mid-January 2023 on the status of implementation of silent eating and (2) administrative data on daily class closures at each school, recorded by the prefecture’s board of education. The data in (1) showed that 45 schools in 11 cities in Chiba Prefecture had revised their silent eating rules. In our analysis, we used these 45 schools and their classes as our control schools. Meanwhile, 157 schools in these 11 cities maintained their silent eating rules, and we used these schools and their classes as the treated schools.

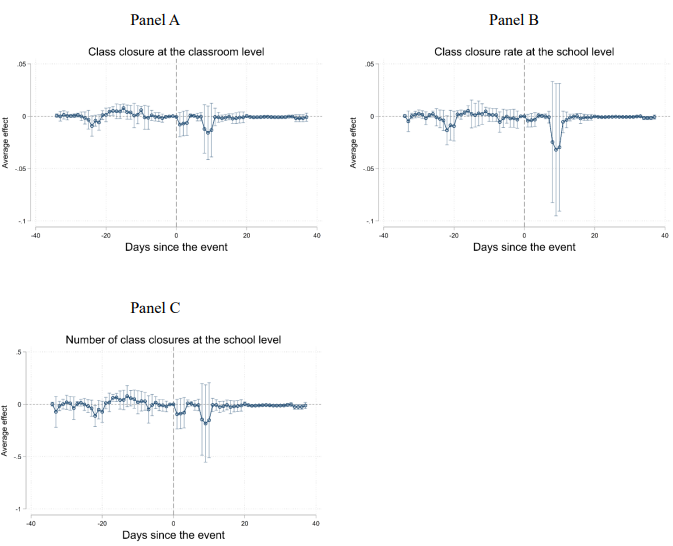

Based on the results of an event study analysis using the de Chaisemartin and D’Haultfoeuille (2020) estimator, we were able to confirm that the class closure rate at the classroom level and school level, as well as the number of class closures at the school level, decreased around 10 days after lifting the silent eating protocol. However, none of the estimated coefficients were statistically significant and all estimated coefficients subsequently returned to zero (see the figure below). Applying a difference-in-differences model with two-way fixed effects, we found that the estimated values for the average treatment effects under each outcome were close to zero and insignificant. We were therefore unable to confirm any compelling evidence to support the idea that silent eating helped to prevent class closures.

These results indicate that silent eating during school lunchtimes had an extremely small and statistically insignificant effect on reducing the number of class closures and the class closure rate. This suggests that lifting the requirement to eat silently would not increase the risk of class closure. Existing empirical research indicates the possibility that silent eating may have a side effect on children’s skill formation. Our findings suggest that governments should account for the dynamic nature of pandemics and provide greater flexibility to adopt to changing circumstances in their policies, striking a balance between infection prevention measures and the overall well-being and developmental needs of children.