| Author Name | INOUE Hiroyasu (University of Hyogo / RIKEN Center for Computational Science) / TODO Yasuyuki (Faculty Fellow, RIETI) |

|---|---|

| Research Project | Research on relationships between economic and social networks and globalization |

| Download / Links |

This Non Technical Summary does not constitute part of the above-captioned Discussion Paper but has been prepared for the purpose of providing a bold outline of the paper, based on findings from the analysis for the paper and focusing primarily on their implications for policy. For details of the analysis, read the captioned Discussion Paper. Views expressed in this Non Technical Summary are solely those of the individual author(s), and do not necessarily represent the views of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI).

In recent years, the import of parts and components from China and ASEAN countries has been frequently disrupted due to economic and social restrictions associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, leading to the substantial reduction in production in Japan. Factors such as the deepening of the U.S.-China tensions and the Russo-Ukrainian War have also resulted in trade restrictions based on national security concerns, which have led to reductions in imports and exports, as well as rising concern over the future.

Given this state of affairs, this paper uses simulations to analyze the impact on the Japanese economy of a potential exogenous shock leading to a reduction in Japan’s materials, parts, and components imports, as well as its product exports.

The most notable feature of this paper is the way that we fit detailed supply chain data contained by more than 1 million firms in Japan into an economic model to consider the possibility that a reduction in imports and exports could be propagated and amplified through domestic supply chains. Data limitations meant that previous studies either considered only domestic supply chains without accounting for imports and exports by individual firms or considered only relationships between industries without accounting for corporate supply chains. This study solves these problems for the first time by linking together inter-firm domestic supply chain data from Tokyo Shoko Research with per-firm import and export amounts from the Basic Survey of Japanese Business Structure and Activities (Kigyo Katsudo Kihon Chosa, hereafter the BSJ) conducted by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI).

As a result, we found that disruptions in the import of parts and components propagate through supply chains to affect downstream firms, and therefore lead to a larger decline in production than export disruptions. This propagation through supply chains means that the impact of import disruptions increases dramatically as the level or duration of the disruption increases.

For example, if 80% of imports from around the world are disrupted for four weeks, Japan’s value added production only decreases by about 2.9% during this period, but if the disruption continues for two months, this decrease rapidly worsens to about 26%. On the other hand, if the contraction is mild, with a disruption of 40% of imports, production only decreases by about 2%, even if the disruption continues for two months. The impact of export disruptions was relatively slight compared to import disruptions, with a decrease in production of only 4.4% even in the case of an 80% disruption lasting two months.

Moreover, an examination of the impact of two-month import and disruptions of 80% of imports from China and other Asian countries reveals an overwhelmingly large impact. (We have been unable to conduct an analysis for individual countries, except for China, as the information on trade partners in the BSJ is classified by region into China, Asia excluding China, North America, Europe, the Middle East, and other regions.)

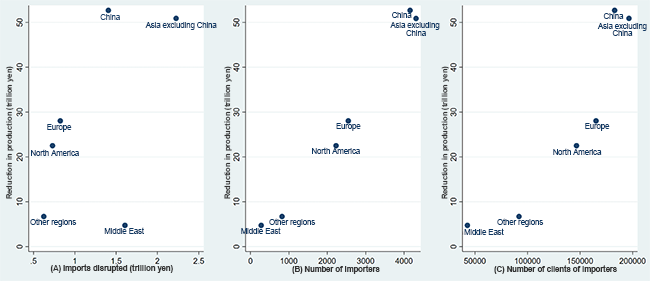

Figure 1(A) shows the relationship between the decrease in production amount resulting from import disruptions and the value of imports disrupted for each exporting region. There is no apparent simple relationship indicating that larger amounts of imports disrupted lead to larger decreases in production amount. A clearer correlation is visible between the decrease in production amount and the number of firms that import from each region (Figure 1(B)) and the number of customers of these firms (Figure 1(C)), indicating that decreases in production due to import disruptions are dependent on the supply chain structure.

These results also show that firms can mitigate some of the domestic production impacts of import disruptions if they are able to substitute for the affected goods through procurement from domestic suppliers. For example, in the case of a disruption of 80% of imports from around the world lasting two months, the decrease in production (the “reduction rate”) improves from 26% to 20%.

There is very little difference in this improvement in the decrease in production regardless of whether we assume that firms facing supply disruptions for parts and components are able to flexibly find new suppliers or that firms can only initiate new transactions with the suppliers of other firms with which they share common suppliers. In other words, even if disruptions in the import of materials, parts, and components are unavoidable, it is possible to mitigate the impact of these disruptions through a relatively minor restructuring of domestic supply chains.

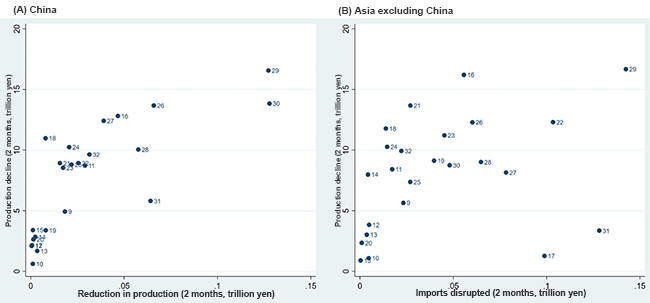

We also analyzed the impact of import disruptions that are limited to specific sectors (defined at the two-digit level according to the Japan Standard Industrial Classification). Figures 2A and 2B show the relationship between the amount of imports disrupted and the decrease in production, assuming imports to specific sectors from China and other countries in Asia, respectively, are disrupted.

The impact of imports from China is large for machinery (26, 27), electronic components (28), electrical appliances (29), and information and telecommunications equipment (30), but the impact of imports from other countries in Asia is also significant for chemicals (16), ceramics (21), steel (22), etc. The impact of import disruptions in the automotive industry (31) is only small relative to the amount of imports. This is thought to be due to the upstream position of imported parts and components in domestic supply chains in the electrical appliances and electronics industries, which results in a flow-on effect downstream. By contrast, the imported parts and components in the automotive industry are positioned farther downstream in supply chains.

These results indicate the need for caution regarding the following points in cases where external factors cause a disruption in the import of parts or components, or where import restrictions are imposed for national security reasons.

- (1) The impact of import disruptions is amplified through domestic supply chains and increases dramatically with the severity and duration of the disruption. It is therefore vital to keep the degree and duration of the disruption to a minimum.

- (2) The size of the impact of import disruptions also depends on the structure of supply chains. In the case of an unavoidable disruption of imports from a certain country or sector, the size of the impact should not be evaluated solely based on the level of imports.

- (3) The impact of import disruptions can be substantially mitigated through substitution for the disrupted materials, parts, and components using domestic supply chains. It is therefore crucial to anticipate the potential need for such substitution before any disruption occurs.

[Click to enlarge]

[Click to enlarge]