| Author Name | Willem THORBECKE (Senior Fellow, RIETI) / Ahmet SENGONUL (Sivas Cumhuriyet University) |

|---|---|

| Download / Links |

This Non Technical Summary does not constitute part of the above-captioned Discussion Paper but has been prepared for the purpose of providing a bold outline of the paper, based on findings from the analysis for the paper and focusing primarily on their implications for policy. For details of the analysis, read the captioned Discussion Paper. Views expressed in this Non Technical Summary are solely those of the individual author(s), and do not necessarily represent the views of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI).

Turkey has chosen the unorthodox approach of lowering interest rates in the face of high inflation. It argues that the resulting exchange rate depreciation will spur exports. The Turkish real effective exchange rate depreciated by 70% between 2012 and 2022. Two other shocks, the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine War, also struck Turkey. How do massive depreciations, the coronavirus pandemic, and the Russia-Ukraine War affect Turkish imports and exports and Turkish businesses?

In theory exchange rate depreciations should increase the price competitiveness and thus the volume of exports. They should also decrease the purchasing power of domestic agents and thus the volume of imports. The magnitude of these effects is an empirical question.

Results from several extimation techniques indicate that exchange rate depreciations do not increase exports. The findings also indicate that they cause a large decrease in imports. Given the important role that imported inputs play in Turkey’s production structure, these results suggest that lira depreciations are harmful for Turkey’s firms.

To further investigate this issue, we examine the exposure of Turkish stock returns to exchange rates. Theory indicates that stock prices equal the expected present value of future cash flows. Thus the way that exchange rates affect stock prices can shed light on how they impact Turkish firms. We find that stock returns for most sectors fall when the lira depreciates.

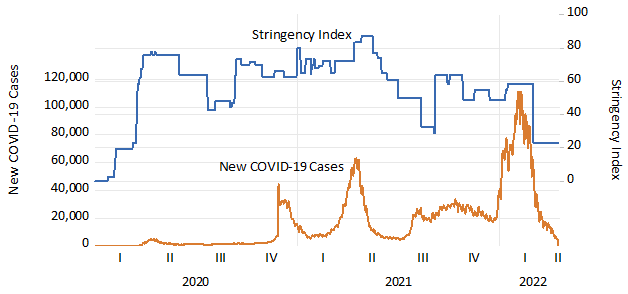

Turkey has also faced five waves of COVID-19 infections. The first wave peaked in April 2020 with under 5,000 new cases per day, the second wave peaked in December 2020 with 33,000 new cases, the third wave peaked in April 2021 with over 60,000 new cases, the fourth wave peaked in November 2021 with just over 30,000 new cases, and the fifth wave peaked in February 2022 with over 100,000 new cases. As of the end of April 2022 Turkey has suffered 1,149 deaths per million people. This is the 84th highest number out of 228 countries examined.

The Turkish government adopted a range of measures to slow the spread of COVID-19. It suspended domestic and international flights. It imposed curfews on citizens over the age of 65 and on others. It replaced face-to-face teaching with online teaching. It imposed work bans on sectors that require close contact such as hairdresser services, shopping malls, restaurants, cafes and tourist businesses.

Figure 1 shows how the stringency of Turkey’s response to COVID-19 has varied over time and as the number of new cases has waxed and waned. The stringency index is calculated by the Oxford Coronavirus Government Response Tracker project. It evaluates policy strictness in nine areas: school closures; workplace closures; cancellation of public events; restrictions on public gatherings; closures of public transport; stay-at-home requirements; public information campaigns; restrictions on internal movements; and international travel controls. Stringency in each area on each day is rated between 0 and 100. The overall index is the simple average of the stringency values in each of the nine areas.

Figure 1 shows that immediately after the first coronavirus case was detected the government adopted strict measures. The stringency index in March 2020 rose from 19 to 76. The government eased restrictions starting in June 2020 but tightened them again in September and kept them tight during the second and third waves. As the third wave abated in May 2021 the government eased restrictions but tightened them again during the fourth and fifth waves. As the fifth wave passed, the government eased restrictions in March 2022.

To investigate the relative importance of stringent policies and new COVID-19 cases we include the changes in these variables in a regression to explain returns on the aggregate Turkish stock market. The coefficient on the change in the stringency index is negative and significant while the coefficient on the change in the number of new cases is not statistically significant. The coefficient on the stringency index indicates that the increase in the index between January and March 2020 reduces aggregate stock returns by 3%. These results indicate that it is not the number of coronavirus cases itself but rather the government’s response to the pandemic that suppressed stock prices and economic activity in Turkey.

The Russia-Ukraine War that began on 24 February 2022 presents a new set of challenges. Turkey imports almost 80% of its wheat and sunflower oil from Russia and Ukraine. It receives almost 20% of its tourist arrivals from Russia and Ukraine. It also receives 40% of its natural gas and petroleum from Russia. Higher commodity prices arising from the war could stoke inflation. The headwinds that the war is causing in Europe could slow demand in a key export market.

On the other hand, the war presents opportunities. President Erdoğan’s efforts to broker peace raises Turkey’s stature in the international community. Turkish drones have been successful against Russian weapons, increasing demand for Turkish defense products. The withdrawal of many companies from Russia opens opportunities for Turkish firms to expand in Russia.

To shed light on how the war is impacting Turkish businesses, we estimate a macroeconomic model for the Turkish aggregate stock market over the 21 February 2002 to 23 February 2022 period and then use actual out-of-sample values of the right-hand side variables to forecast returns over the first two and a half months of the war. The results indicate that the Turkish stock market has performed much better than expected during the war.

In summary we find that lira depreciations cause large falls in imports but do not increase exports. They also decrease stock prices for many sectors. Nevertheless, the Turkish economy has remained resilient over the last three years. During the COVID-19 pandemic, it has benefitted from a relocation of supply chains away from Asia. During the first few months of the Russia-Ukraine war, its stock market has done much better than would be predicted based on a forecasting equation. These successes, however, have come in spite of and not because of the weak lira. A stonger currency would increase the purchasing power of domestic firms and consumers. This is important when firms depend on imported inputs and when consumers purchase many imported goods such as food. A stronger currency would also do little to slow exports. Policymakers should consider choosing policies to strengthen the Turkish lira.

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/metrics-explained-covid19-stringency-index and https://ourworldindata.org/covid-cases.