| Author Name | Willem THORBECKE (Senior Fellow, RIETI) |

|---|---|

| Research Project | East Asian Production Networks, Trade, Exchange Rates, and Global Imbalances |

| Download / Links |

This Non Technical Summary does not constitute part of the above-captioned Discussion Paper but has been prepared for the purpose of providing a bold outline of the paper, based on findings from the analysis for the paper and focusing primarily on their implications for policy. For details of the analysis, read the captioned Discussion Paper. Views expressed in this Non Technical Summary are solely those of the individual author(s), and do not necessarily represent the views of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI).

Macroeconomy and Low Birthrate/Aging Population (FY2016-FY2019)

East Asian Production Networks, Trade, Exchange Rates, and Global Imbalances

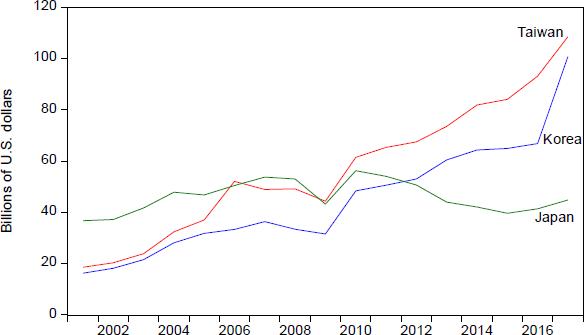

Japan is upstream in global value chains, and in every year since 1994 electronic parts and components (ep&c) has been Japan's second leading export category at the International Standard Industrial Classification (ISIC) 4-digit level. Japan was the world's largest exporter of ep&c before the GFC, but by 2017 Taiwan and South Korea each exported more than twice the value of ep&c that Japan did (Figure 1). How did Japan lose its comparative advantage in producing microprocessors, flat-panel displays, integrated circuits, and other parts and components?

Integrated circuits and similar goods have become commoditized and Japanese firms are now competing in these products based on price. Facing fierce competition from Korea and Taiwan, Japanese firms may lack pricing power. If they cannot raise prices, they suffer compressed profit margins when confronted with adverse shocks.

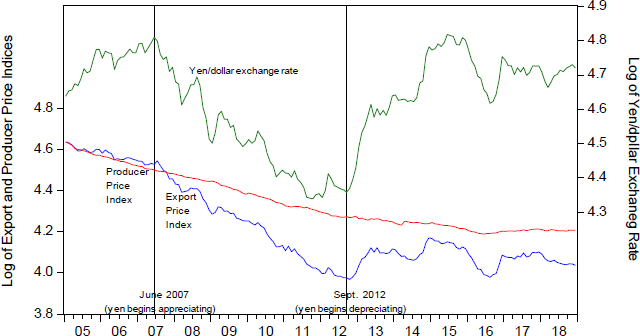

Japanese companies faced a negative shock in the form of an appreciating yen beginning in June 2007 (see Figure 2). The GFC generated safe haven capital inflows that caused the yen to appreciate 45 percent against the U.S. dollar between June 2007 and September 2012. Figure 2 shows that the yen price of ep&c exports over this period fell 35 percent relative to yen production costs, where production costs are measured using the producer price index for ep&c.

This paper investigates whether the strong yen caused yen export prices and thus the value of ep&c exports to fall. Results from exchange rate pass-through equations indicate that yen appreciations led to one-for-one decreases in yen export prices. This implies that exporters followed a pricing-to-market strategy.

The paper then examines whether the appreciating yen caused export volumes to fall by estimating export elasticities using a panel of Japan's exports to major importing countries. The results point to small price elasticities. This makes sense given that exporters adjusted foreign currency prices to remain competitive in response to exchange rate shocks.

Since an appreciation causes yen export prices to fall relative to yen production costs, exchange rate changes should affect the profitability of ep&c producers. To examine this issue the paper estimates exchange rate exposure equations for Japanese semiconductor stocks. Theory implies that stock prices equal the expected present value of future net cash flows. Thus these prices provide information about future profitability. The results indicate that yen appreciations lead to large decreases in semiconductor stocks and that New Taiwan dollar depreciations also lead to large decreases in semiconductor stocks. With the advent of the GFC, not only did the yen appreciate but the NT dollar depreciated. Both of these currency movements acted as negative shocks that lowered the profitability of Japanese ep&c producers.

The profitability shock that Japanese firms suffered after the GFC hampered their ability to invest. Maintaining competitiveness in this industry requires massive investment in physical capital and in research and development. Investment by Japanese ep&c firms tumbled after the GFC and never recovered. The endaka shock thus triggered a long-term decline in the industry.

This experience offers a couple of lessons. First, competing based on price in commoditized industries is onerous. Japanese companies should focus on products where craftsmanship is valued. An example of this is the image sensors that Sony produces. Second, unexpected shocks can cause an industry's outlook to turn on a dime. It is important for Japanese companies to save during good times to be prepared for downturns. During the bad times they should focus on long-term viability and fending off lasting damage.

Source: CEPII-CHELEM database.