| Author Name | Willem THORBECKE (Senior Fellow, RIETI) |

|---|---|

| Research Project | East Asian Production Networks, Trade, Exchange Rates, and Global Imbalances |

| Download / Links |

This Non Technical Summary does not constitute part of the above-captioned Discussion Paper but has been prepared for the purpose of providing a bold outline of the paper, based on findings from the analysis for the paper and focusing primarily on their implications for policy. For details of the analysis, read the captioned Discussion Paper. Views expressed in this Non Technical Summary are solely those of the individual author(s), and do not necessarily represent the views of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI).

Macroeconomy and Low Birthrate/Aging Population (FY2016-FY2019)

East Asian Production Networks, Trade, Exchange Rates, and Global Imbalances

The People's Republic of China (PRC) is the second largest economy in the world, the final link in East Asian supply chains, and a voracious consumer of natural resources. The value of the PRC's imports each year exceeds a trillion dollars. Many firms depend on exports to the PRC for a large share of their profits. The PRC's economy, after growing at close to double-digit rates since the early 1990s, has encountered turbulence. Net capital outflows have accelerated since 2014 and generated depreciation pressures. Overcapacity has emerged in several sectors including steel, shipbuilding, and chemicals. Trade wars and economic challenges abroad are generating headwinds for the Chinese economy. How will imports from the PRC's trading partners be affected?

To answer this question, it is necessary to distinguish between different types of imports and different countries. For instance, imports for processing can only be used to produce goods for re-export while ordinary imports are destined primarily for the domestic market. Processed exports flow disproportionately to high income countries. Imports for processing should thus depend on demand conditions and exchange rates in the high income countries purchasing the final good, while ordinary imports should depend on demand conditions and exchange rates in the PRC. Countries such as Australia and Brazil that export raw materials such as iron ore should be sensitive to slowdowns in sectors such as steel that require natural resources.

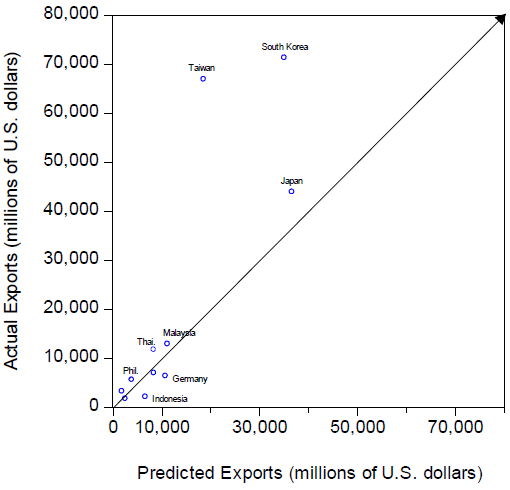

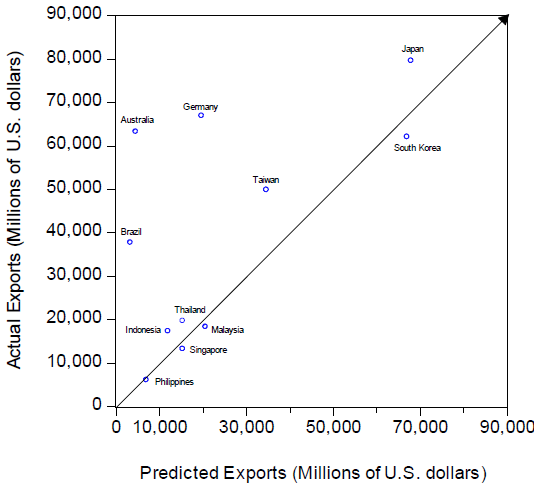

To shed light on exporters' exposures to the Chinese economy, this paper employs a gravity model. The gravity model is a workhorse for explaining bilateral trade flows. It controls for distance and economic size. Figures 1 and 2 plot the difference between actual exports to the PRC in 2016 and those predicted by the gravity model. Figure 1 presents results for processed exports and Figure 2 presents results for ordinary exports. In the figures, values above the diagonal line indicate that exports are more than predicted and values below the line indicate that exports are less than predicted. The vertical distance between the observation and the diagonal line measures the degree of over- or under-prediction. Figure 1 indicates that East Asian supply chain economies such as Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan export many more parts and components to China for re-export than one would predict. Figure 2 indicates that primary goods producers such as Australia, Brazil and Saudi Arabia and producers of sophisticated machinery such as Germany and Japan export many more goods to the Chinese domestic market than predicted.

The paper then investigates import elasticities for China. For processing trade, it reports that there is a close relationship between imports for processing and processed exports and that exchange rate elasticities are insignificant. For ordinary trade, it reports income elasticities of 1.6 and exchange rate elasticities that are of the expected sign and equal to 0.4. These results imply that a reduction in processed exports driven by factors in advanced economies and a reduction in Chinese GDP matter for Chinese imports. A renminbi depreciation would only matter if it were large.

Several policy lessons flow from these findings. Countries such as Australia and Indonesia whose exports include a large share of primary products are very exposed to a slowdown in China. They should seek to diversify their export base to include more manufactured products. Indonesia should also seek to strengthen its connection to global value chains (GVCs) by improving infrastructure and human capital and by fighting corruption. Joining GVCs would promote technological upgrading by allowing domestic workers to acquire new skills and domestic firms to learn new management techniques.

Japan, Korea and Taiwan are especially exposed to a slowdown in processing trade. Their challenge is compounded because China's high investment levels in recent years have enabled firms in the PRC to substitute parts and components produced in China for imported parts and components. Japanese, Korean and Taiwanese firms should innovate and produce cutting edge intermediate goods to ensure that their products remain in demand in China.

All of East and Southeast Asia including China would benefit if multinationals and others involved in processing trade could find new sources of demand and become less dependent on demand in the West.

It is an old saw in economics that diversification reduces risk. In the face of slowdowns in China and the rest of the world, this maxim is especially relevant. Companies and countries should diversify their export base, diversify their trading partners, and reduce their exposure to the PRC or any other single country. They should also specialize and find niches where they have comparative advantage.

Source: CEPII-CHELEM Database and calculations by the author.

Source: CEPII-CHELEM Database and calculations by the author.