China has been plagued by COVID-19 and its aftermath since the beginning of 2020, with its economy fallen into a recession. Although economic growth is expected to pick up in the months ahead as the pandemic subsides, it is still likely to drop sharply for 2020 as a whole. The government has responded by focusing its economic policy on fiscal and financial support for small-and-medium sized companies adversely affected by the pandemic, rather than large-scale stimulative economic measures, which involve major side effects.

Decline in economic growth rate due to shrinking supply and demand

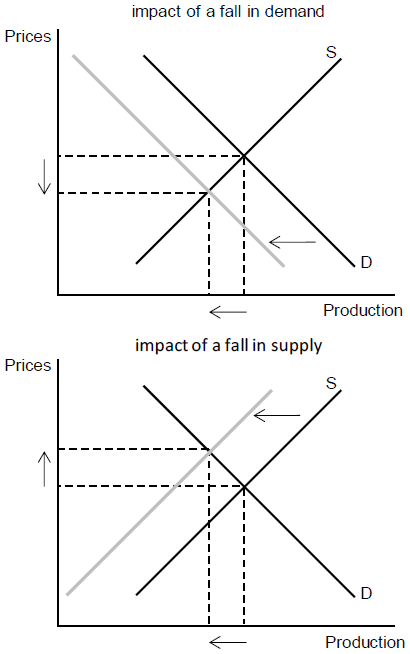

The economic impact of the spread of COVID-19 can be considered separately in terms of supply and demand. Moreover, the impact of policies taken to prevent the spread of infection, such as movement restrictions on people, is greater than the impact from the spread of the disease itself.

First, on the demand front, many people are refraining from going out, either voluntarily or under government-imposed regulations. This is having an enormous impact on the service sector, such as retail, food services, travel, and entertainment.

On the supply front, meanwhile, the government took steps to extend the Spring Holiday (Chinese New Year). Moreover, while the movement of people is severely restricted, some employees are not able to go to work, and many companies are behind in normalizing their business despite the end of the holiday. In addition, in some industries, the supply of parts and production goods has narrowed, resulting in many companies being forced to cut back or shut down operations in downstream sectors in the supply chain. These include not only Chinese companies, but also multinational companies that have production bases in China or that rely heavily on China to supply parts. The investment environment in China had already deteriorated in the wake of U.S.-China trade friction, and if the "Chinese risk" is judged to be even higher as a result of the spread of COVID-19, companies will accelerate the transfer of production bases overseas.

Whether due to demand or supply factors, the impact on production (represented by GDP) due to the spread of COVID-19 is negative in either case, but their combined impact on prices is the opposite. However, while the reduction in production due to a decline in demand (shifting the demand curve to the left) is a factor in the decline in prices, the reduction in production due to a decline in supply (shifting the supply curve to the left) leads to an increase in prices (Figure 1). The two tend to offset each other, and so the overall effect of the spread of COVID-19 on prices is expected to be more or less be neutral.

Slower economic growth

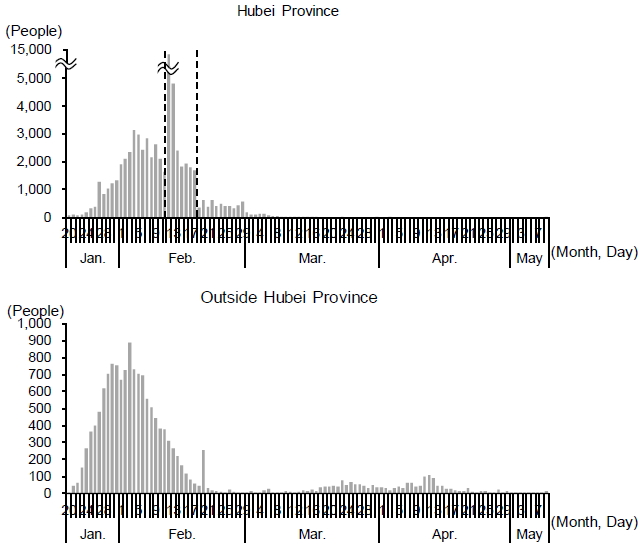

While there has been criticism that the government's initial response had been delayed, following President Xi Jinping's instruction on January 20, 2020 that the spread of COVID-19 must be taken seriously, tough measures were implemented one after another to curb and to control the disease:

(1) Wuhan, the capital city of Hubei Province and the epicenter of COVID-19, was locked down on January 23, and other cities in Hubei Province followed shortly after. This involved not only prohibiting people from leaving these cities, but also severely restricted movement within them.

(2) The Spring Holiday was extended from "until January 30, 2020" to "until February 2, 2020" (and extended further in some regions).

(3) Each region limited the influx of people from areas where the disease is spreading.

The government's measures have been successful, and the number of newly confirmed infections in mainland China peaked in early February outside Hubei Province and in mid-February inside Hubei Province, with COVID-19 mostly subsided by early March (Figure 2). Against the background, the lockdown on cities in Hubei Province other than Wuhan was lifted on March 25, with Wuhan following on April 8.

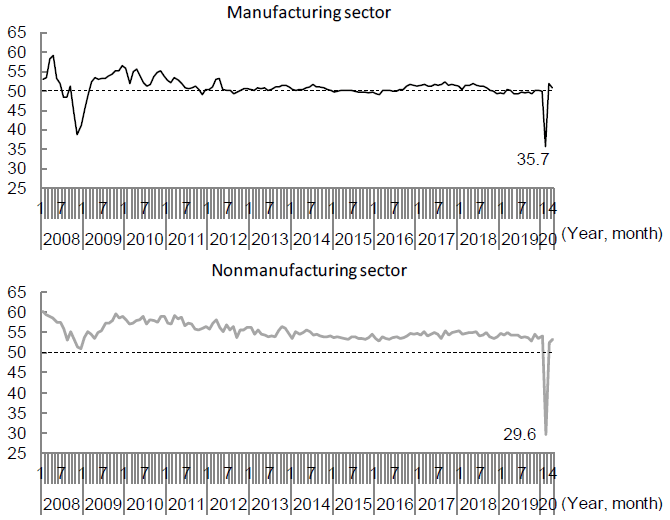

Thus the effects of the spread of COVID-19 were concentrated in the first quarter of 2020, especially in February, and the economic growth rate for the quarter dropped to -6.8%. The Purchasing Managers' Index (PMI) for February fell to record lows of 35.7 in the manufacturing sector and 29.6 in the nonmanufacturing sector (mainly the service industry), below the figures seen during the Lehman shock of 2008, with the decline in the nonmanufacturing sector being especially large (Figure 3). However, even if COVID-19 comes to an end in the second quarter and the economy heads into recovery by the second half of the year, the annual economic growth rate for 2020 is likely be sharply lower than the 6.1% recorded a year earlier.

Corporate support rather than stimulative economic measures

Most companies must continue to pay fixed costs such as wages, interest, and rent, while their incomes have been significantly reduced due to the suspension of operations and delays in business resumption, causing their cash flow to deteriorate. If corporate bankruptcies increase as a result, the problem of unemployment and bad loans could become increasingly serious. To avoid this situation, the government has come out with measures to help damaged companies, focusing on limited-time tax relief on the financial front and expanding policy lending on the monetary front. As part of this, the Executive Meeting of the State Council on February 25, 2020, presided over by Premier Li Keqiang, decided to implement measures to reduce the value-added tax (VAT; equivalent to the consumption tax in Japan) for small businesses. The period for the reduction is three months from March to May, and small businesses in Hubei Province will be exempt from VAT while in other areas the tax rate will be reduced from 3% to 1%. Moreover, the People's Bank of China has announced that it will establish a 500-billion-yuan credit line for small and medium-sized banks specifically for refinancing and rediscounting to support agriculture and small businesses, in addition to the 300-billion-yuan credit line already established specifically for key companies involved in controlling infectious disease.

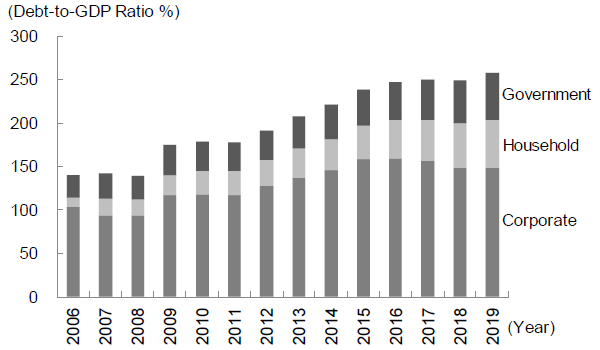

With economic growth slowing down sharply, there are growing calls for the implementation of large-scale economic measures, mainly infrastructure investment and monetary easing, as was done after the Lehman shock of 2008. However, the government should proceed cautiously because the associated side effects of such measures are expected to be large.

First of all, China's non-financial sector (corporate, household, government) debt-to-GDP ratio, which has risen sharply since the Lehman crisis in 2008, reached the dangerous level of 258.7% at the end of 2019 (Figure 4). Implementing large-scale stimulative measures could exacerbate the debt problem and, in turn, lead to a financial crisis. In particular, many infrastructure investments carried out in the name of economic measures have low profitability. In addition to construction costs, the repayment of funds and maintenance costs will represent a heavy burden in the future.

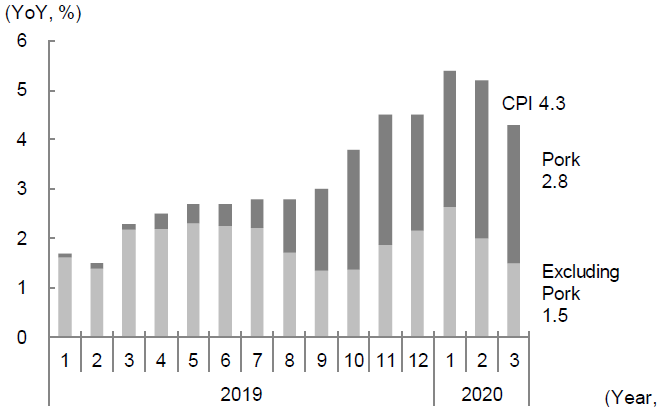

In addition to this, there is growing concern about inflation. Mainly reflecting the rise in pork prices due to the effect of pork cholera, the inflation rate in the Consumer Price Index (CPI) reached 5.0% year-on-year in the first quarter of 2020 (5.4% in January, 5.2% in February and 4.3% in March) (Figure 5). Monetary easing and fiscal expansion could spur an upward trend in inflation.

- The Contribution of Rising Pork Prices -

Meanwhile, monetary easing, through efforts such as the lowering of interest rates, could lead to further declines in the renminbi rate, which is already weak in the wake of U.S.-China trade friction and the spread of COVID-19, and intensify, in turn, trade friction with the United States.

Under these constraints, even if economic measures were implemented, their scale would likely be limited.

Concerning boomerang effects from abroad

COVID-19, which began in China, has since spread overseas. Stock prices have plummeted in major markets since late February amid concerns about its impact on the global economy. The slump in overseas markets will spur a further slowdown in Chinese exports, which had already become apparent in the wake of U.S.-China trade friction. Curbing with this deterioration in the internal and external environment has become a major challenge facing the Chinese economy.

The original text in Japanese was posted on March 12, 2020.

Updated on May 13, 2020.