In response to the global economic crisis that followed the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008, protectionism has risen in the United States. This trend has become more conspicuous since the inauguration of the Trump administration in 2017. The U.S. protectionism is targeted at China in particular. On the other hand, China is actively promoting an opening-up policy, mainly by implementing the "Belt and Road" initiative and inviting investment from foreign companies in order to avoid being isolated from the global economy. However, these efforts have not yet achieved their intended goals.

U.S. Leaning Further toward Protectionism

In the United States, since taking office after winning the presidential election on a protectionist campaign platform, President Trump has taken a succession of policy measures that have changed the existing global trade regime. For example, he has pulled the United States out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), imposed additional tariffs on imports of steel and aluminum products from many countries, including some U.S. allies, and launched a trade war against China. He has also concluded the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) in place of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) after renegotiations with the NAFTA partners, escalated U.S.-Europe trade friction, and called for the reform of the World Trade Organization. In trade negotiations with foreign governments, President Trump has maintained a particularly aggressive stance toward China.

Between President Nixon's visit to China in 1972 and the period of the Obama administration, the United States maintained a policy of engagement with that country. However, against the backdrop of China's rise as an economic superpower while maintaining political and economic systems vastly different from those of the West, the United States under the Trump administration has come to regard China as a strategic competitor and drastically changed its China policy. To contain China's rise, it is promoting a "decoupling policy," which seeks to disengage the Chinese economy from the U.S. economy by restricting the flows of trade, investment, people and information between the two countries.

Specifically, in March 2018, the United States announced sanctions against China centering on the imposition of additional tariffs based on a report on China issued under Section 301 of the U.S. Trade Act of 1974. Subsequently, the United States and China have engaged in tit-for-tat tariff impositions against each other, causing their trade friction to escalate into a trade war. Although 13 rounds of high-level trade talks and two summit meetings between President Trump and President Xi Jinping have been held, a final agreement has not yet been reached. Meanwhile, in August 2018, a series of laws apparently intended to suppress the development of China's high-tech industry, including one that enhanced restrictions on inward foreign direct investment, were enacted in the United States and followed by the announcement in May 2019 of the policy of banning Huawei from the U.S. market. The U.S.-China friction has not only escalated into a trade war but it is also threatening to develop into a high-tech war. Under these circumstances, some U.S. allies, such as the EU and Japan, are also moving to restrict technology transfer to China.

China Upholding Opening-Up Policy

In response to the rise of protectionism in the United States after the Lehman crisis and the recent U.S. efforts to decouple from the Chinese economy, the Chinese government has aimed to further open the Chinese economy to the outside world, mainly by implementing and advancing the Belt and Road initiative and inviting investment from foreign companies. The latest round of opening up of the Chinese economy covers a broad range of regions and industries. The emphasis is placed on institution building, and the initiative is a voluntary activity on the part of China that does not require partner countries to make corresponding contributions.

In his speech at the G20 Summit in Osaka on June 28, 2019, President Xi expressed China's resolve to push ahead with the Belt and Road initiative. The professed goal is integrating more countries and regions into the globalization process and developing win-win relationships by mobilizing more resources, strengthening interconnectedness, unlocking potential drivers of growth and linking various markets. In addition, President Xi cited the following five principles of China's opening-up policy.

(i) Opening the door wider to foreign companies

(ii) Promoting a voluntary expansion of imports

(iii) Continuously improving the business environment

(iv) Fully implementing equal treatment

(v) Strongly promoting economic and trade negotiations

Promoting the Belt and Road Initiative

The Belt and Road initiative, proposed by President Xi in 2013, is an initiative that aims to create a vast economic area that straddles Asia, Europe and Africa. To provide financial support for infrastructure development in the regions covered by the initiative, the Silk Road Fund and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank have been established under China's leadership. The total amount of direct investment made by Chinese companies in those regions between 2013 and 2018 was more than 90 billion dollars, while the total amount of sales from projects implemented and completed by Chinese companies was more than 400 billion dollars ("The Belt and Road Initiative: Progress, Contributions and Prospects," Office of the Leading Group for Promoting the Belt and Road Initiative).

However, most areas covered by the Belt and Road initiative are developing countries and regions and, therefore, do not possess advanced technologies that China wants to introduce and are high-risk investment destinations. When thinking about the future of the Belt and Road initiative, we may consider the following three scenarios.

(i) Optimistic scenario: The Belt and Road initiative developing into a Chinese version of the Marshall Plan

The series of measures taken by the Chinese government to implement the Belt and Road initiative are reminiscent of the Marshall Plan, which was carried out by the United States to support Euopean countries after the end of World War II. While the Marshall Plan made great contributions to the post-war recovery of these countries, it also provided U.S. companies with a huge foreign market. The Belt and Road initiative, as a Chinese version of the Marshall Plan, could also lead to the development of win-win relationships between China and partner countries.

(ii) Pessimistic scenario: The Chinese economy declining due to "imperial overstretch" (Note 1)

Due to poor investment efficiency and unstable political and economic situations in regions covered by the Belt and Road initiative, a significant amount of non-performing loans could accumulate, imposing a heavy burden on China. Contrary to its intended goals, the promotion of the Belt and Road initiative could trigger a decline of the Chinese economy.

(iii) Median scenario: "Cross the river by feeling the stones" (Note 2)

When promoting the Belt and Road initiative, China could follow a gradualist approach based on trial and error, as adopted by China in its process of reform and opening up that started in the late 1970s, with the areas being covered expanding from "points" to lines, and then further to "surfaces."

Of the three scenarios, the median scenario is the mostly likely. In this scenario, however, the economic benefits to China of the Belt and Road initiative will be limited.

Making Earnest Efforts to Invite Foreign Investment

In addition to promoting the Belt and Road initiative, China is making earnest efforts to invite investment from foreign companies. To that end, China is quickly developing relevant legal frameworks. On March 15, 2019, the new Foreign Investment Law, which replaces the existing three foreign investment laws—the Law on Foreign-funded Enterprises, the Law on Chinese-foreign Equity Joint Ventures, and the Law on Chinese-foreign Contractual Joint Ventures—was enacted (scheduled to be put into force on January 1, 2020) at the second session of the 13th National People's Congress. The new law proclaims the following three policies:

(i) Establishing a foreign investment management system based on pre-establishment national treatment and a negative list system,

(ii) Creating a fair competitive environment for foreign companies operating in China,

(iii) Strengthening the protection of intellectual property rights.

The negative list refers to special administrative measures for the access of foreign investment in certain business sectors by defining the "prohibited" sectors and "restricted" sectors. Foreign companies are not permitted to invest in "prohibited" sectors. When planning to enter "restricted" sectors, they need to undergo screening and obtain approval from the authorities before investing. However, if the sectors that they plan to enter are not on the negative list, they will only be required to register with the authorities. Pre-establishment national treatment refers to the equal treatment of foreign and domestic companies in sectors where entry by foreign companies is not prohibited or restricted based on the negative list. The equal treatment is applicable to companies starting from their date of establishment or of acquisition of market access.

Under the 2018 version of the negative list, the number of items for which investment by foreign companies is prohibited or restricted fell to 48 from the 63 under the 2017 version. Specifically, the restriction on the foreign equity ratio concerning banks was removed, while the upper limit on the foreign equity ratio concerning securities companies, fund management companies, futures trading companies, and life insurance companies was raised to 51%. In 2021, the restriction on the foreign equity ratio will be fully removed in the financial sector (since then, the timing of the full removal has been brought forward one year to 2020). In the automobile sector, the restriction on the foreign equity ratio was removed with respect to new energy vehicles in 2018 and will be removed with respect to commercial vehicles and passenger vehicles in 2020 and 2022, respectively. In addition, the rule limiting the number of Chinese joint venture companies that may be established by the same foreign investor to two companies when they manufacture the same type of finished vehicles was removed (Note 3).

Under the 2019 version of the negative list, the number of items for which foreign investment is prohibited or restricted fell to 40 from the 48 under the 2018 version. Specifically, the rule that had required the establishment of joint ventures or cooperation with Chinese companies with respect to foreign investment in the oil and natural gas extraction industry was removed. In addition, in the value-added communications services sector, call center and data transfer businesses were exempted from restriction. The restriction on foreign investment in the construction of movie theaters was also removed.

Apart from the nation-wide negative list, a negative list applicable specifically to foreign companies operating in pilot free trade zones, which are positioned as testing grounds for the reform and opening-up initiative, was announced for the first time in 2013. Under this list, the number of items for which foreign investment is prohibited or restricted is smaller than under the nation-wide negative list. Since its introduction, this list has been revised almost every year, with the reduction of the number of prohibited and restricted items as the main feature of the revision.

Reversal of the Globalization of the Chinese Economy

Despite the Chinese government's active efforts to implement the opening-up policy, facing the headwinds of rising protectionism in the United States and escalating U.S.-China trade friction, the globalization of the Chinese economy has been reversed.

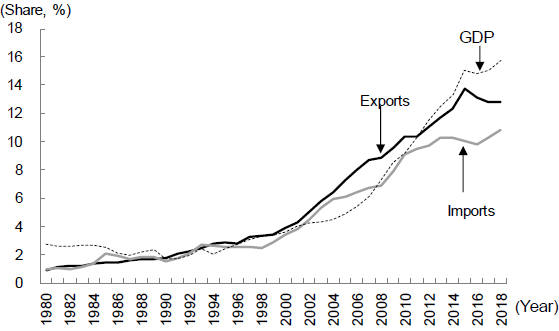

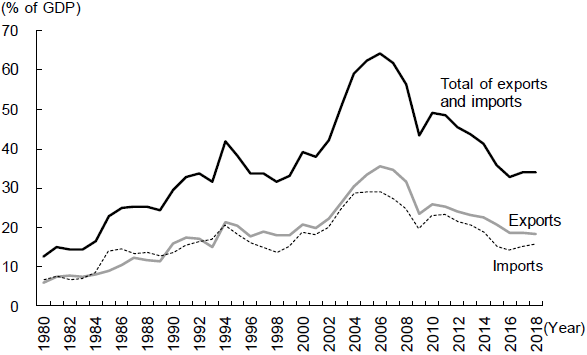

First, in contrast to China's growing share of global GDP, its share of global exports has been declining after peaking in 2015, and its share of global imports have plateaued in recent years (Figure 1). For China, the ratios of exports and imports to GDP and the ratio of overall trade to GDP have all declined steeply since peaking around 2005 (Note 4) (Figure 2).

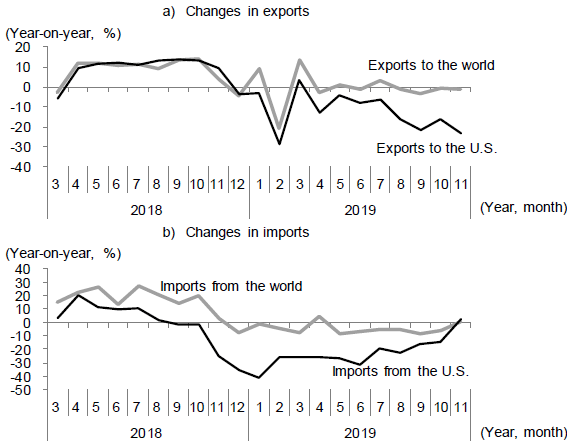

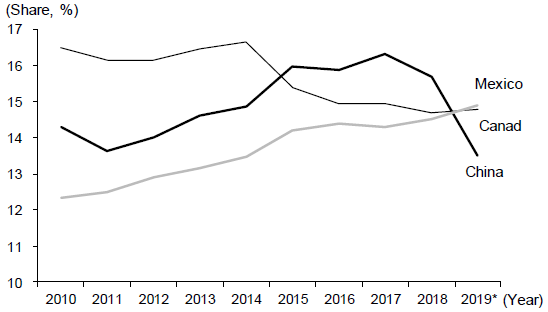

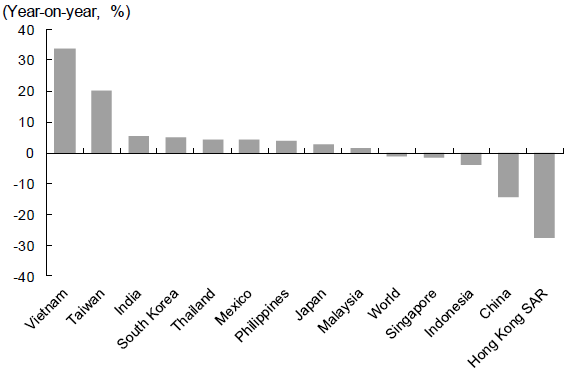

In particular, in 2019, following the outbreak of the U.S.-China trade war, the values (measured in dollar terms) of Chinese exports to and imports from the United States have dropped from their respective levels a year earlier, dragging down the values of Chinese exports to and imports from the world with them (Figure 3). For the United States, for the four years from 2015 to 2018, China was the top trading partner. However, in 2019 (according to the results in January-October), China fell to third place, behind Mexico and Canada, a trend that is emblematic of the decoupling of the U.S. and Chinese economies (Figure 4). In the U.S. market, some portions of imports from China have been replaced by imports from countries and regions competing with China, such as Vietnam, Taiwan, India and South Korea (Figure 5). China, as "the world's factory," is the hub of global supply chains of major industries. If China's loses this advantage due to higher tariff rates and other trade barriers it faces, many multinational companies will have to transfer production from China to other countries.

— Share of Total U.S. Exports and Imports

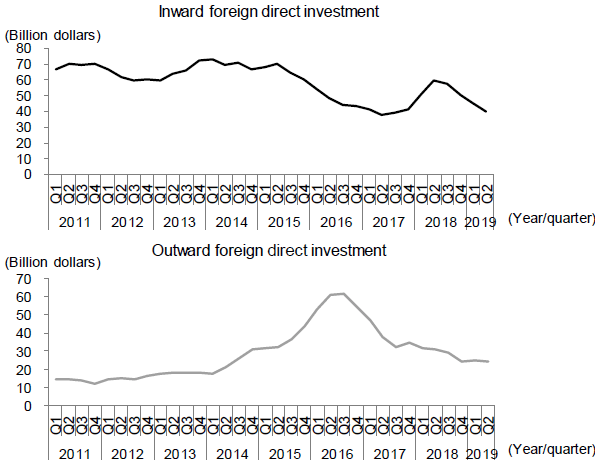

Next, foreign direct investment, including both inward investment and outward investment, has been sluggish (Figure 6). Inward direct investment has slowed down not only because U.S.-China trade friction has dragged on, but also because China's advantage as a production base for exports has declined due to rising wages caused by an increasingly acute labor shortage. On the other hand, as a result of the tightening of regulation in the United States and Europe, China's outward foreign direct investment has fallen steeply since peaking in 2016. In particular, the value of China's direct investment in the United States dropped from 46 billion dollars in 2016 to 29 billion dollars in 2017 and plummeted to only 4.8 billion dollars in 2018. In the first half of 2019, the value of China's direct investment in the United States has remained low, at 3.1 billion dollars (according to a survey by Rhodium Group). For China, which is still in the developing stage, inward foreign investment and outward foreign direct investment are important channels for absorbing technologies from abroad. The loss of China's advantage as a latecomer could further reduce its potential growth rate, which has already been falling as a result of labor shortage.

Improvement in the External Environment as a Precondition for Further Globalization

Since the late 1970s, China had achieved high growth, averaging around 10% annually, for three decades, by riding the wave of economic globalization around the world through reform and its opening-up initiative. In particular, following its accession to the WTO in 2001, China accelerated market reforms, in addition to opening the market wider to the outside world, by taking advantage of pressure from the outside. This injected new energy into the Chinese economy. However, as a result of the rise of protectionism in the United States since the Lehman crisis in 2008, the globalization of the Chinese economy has slowed. Because trade and foreign direct investment involve partner countries and regions, efforts made by one side alone do not always lead to success, as is indicated by China's experience. As a precondition for further globalization of the Chinese economy, the government should not only actively promote the opening-up policy but also maintain good relationships with the United States and other countries and help strengthen frameworks for free international trade and investment.

The original text in Japanese was posted on December 11, 2019.