| Author Name | HANEDA Sho (Nihon University) / KWON Hyeog Ug (Faculty Fellow, RIETI) |

|---|---|

| Creation Date/NO. | January 2026 |

| Research Project | East Asian Industrial Productivity |

| Download / Links |

This Non Technical Summary does not constitute part of the above-captioned Discussion Paper but has been prepared for the purpose of providing a bold outline of the paper, based on findings from the analysis for the paper and focusing primarily on their implications for policy. For details of the analysis, read the captioned Discussion Paper. Views expressed in this Non Technical Summary are solely those of the individual author(s), and do not necessarily represent the views of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI).

Since 2002, the labor share of the manufacturing sector has steadily declined, while the share of imports from China in Japan's total imports has been increasing, suggesting that the two developments may be linked. Similar trends have been observed in other developed economies, giving rise to a substantial literature examining the impact of import competition from China – hereinafter referred to as the "China shock" – on domestic employment. One of the studies in this field is that by Autor et al. (2013), whose approach makes it possible to incorporate regional differences in the impact of the China shock, leading to the widespread use of empirical analyses that take regional and industry characteristics into account. This approach is particularly relevant for Japan, where industrial and labor market characteristics vary substantially across prefectures. However, as national trade and customs statistics are typically aggregated at the national level, measuring the domestic inter-regional impact of the China shock becomes difficult, so as will be detailed later, the approach by Autor et al. may be subject to measurement errors.

Against this background, the aim of this paper is to examine regional differences in the impact of the China shock across Japan at the prefecture and industry level using data from the Trade Statistics of Japan published by the Ministry of Finance and the National Freight Flows Survey (Logistics Census) published by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. In addition, since these variables are aggregated from HS 9-digit classifications, it is also possible to estimate, at the prefecture level, the impact of the China shock categorized by the production stage of goods (intermediate goods, final consumer goods, capital goods), which many previous studies have not been able to incorporate. This is one of the key contributions of this paper. We also empirically examine the relationship between employment trends and the China shock by gender in order to clarify whether the impact of the China shock differs by gender.

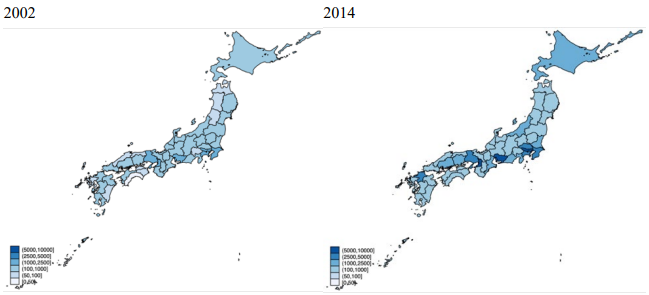

Figure 1 provides an overview of imports of intermediate manufacturing products from China. Aichi was the prefecture with the largest value of intermediate goods imports from China in 2002 with 247.9 billion yen, while Kochi was the prefecture with the smallest amount with 4 billion yen. The prefectures with the largest value of imports, in that order, were Aichi, Kanagawa, Tokyo, Osaka, and Chiba. In 2014, Tokyo accounted for the largest value of intermediate goods imports, with 737.4 billion yen, while Kochi, with 16.1 billion yen, accounted for the smallest figure. The top five prefectures were Tokyo, Osaka, Aichi, Kanagawa, and Saitama, and imports were more concentrated among the top three prefectures than in 2002.

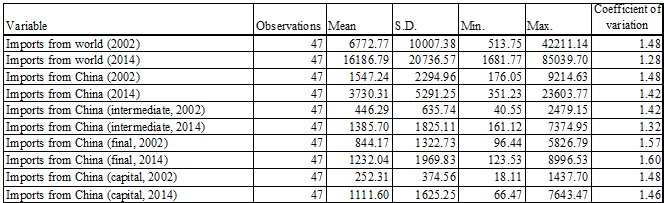

Next, we examine how the degree of dispersion of the imports from China across prefectures has changed using the coefficient of variation. Descriptive statistics for the imports from China and the variable representing imports from the rest of the world, defined in a similar manner as Chinese imports, are presented in Table 1. Starting with imports from the rest of the world, the table shows that the coefficient of variation fell from 1.48 in 2002 to 1.28 in 2014, indicating that the degree of dispersion decreased during this period. Next, looking at imports from China, the degree of dispersion also decreased, from 1.48 to 1.42, but the decrease was relatively small. In other words, compared to imports from the rest of the world, there is greater variation across prefectures in imports from China. Turning to the coefficient of variation for different types of goods, we find that the figure for intermediate goods fell from 1.42 to 1.32, and the figure for capital goods declined slightly from 1.48 to 1.46. On the other hand, the coefficient of variation for final consumer goods imports rose from 1.57 to 1.60. The various results presented here indicate that imports from China vary across regions, and that this variation also changed over time.

Note: The mean, standard deviation, minimum, and maximum are in 100-million-yen units.

The present study empirically examined the impact of imports from China on employment focusing on business establishments in Japan from 2002 to 2014. We found that while the increase in imports of intermediate goods from China may have boosted employment in Japan in the short term, it likely had a negative effect on employment in the longer term. Additional analysis is required to interpret this long-term effect. Finally, the results show that capital goods from China have a negative impact on employment in Japan. This negative impact appears to be particularly pronounced for female workers.

These results indicate that in order for Japanese firms to achieve employment growth, it is important for them to participate in GVCs and use intermediate goods inputs mainly from Asia and low-income countries outside Asia. To do so, more open trade policies, including the reduction of unnecessary trade barriers, are required. Moreover, to boost employment, support for specific worker groups that have been negatively affected by capital goods imports, as well as measures to promote inter- and intra-industry labor mobility within regions and industries are essential.