| Author Name | YAMASHITA Nobuaki (Aoyama Gakuin University / Australian National University / Swinburne University of Technology) / Shiro ARMSTRONG (Non-Resident Fellow, RIETI) |

|---|---|

| Creation Date/NO. | December 2025 |

| Download / Links |

This Non Technical Summary does not constitute part of the above-captioned Discussion Paper but has been prepared for the purpose of providing a bold outline of the paper, based on findings from the analysis for the paper and focusing primarily on their implications for policy. For details of the analysis, read the captioned Discussion Paper. Views expressed in this Non Technical Summary are solely those of the individual author(s), and do not necessarily represent the views of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI).

New evidence on the global spillover effects of great-power trade conflict show how Australian firms adjusted their import sourcing behaviour in response to the 2018–2019 US-China tariff escalation. Using comprehensive Australian import transaction data from 2015–2023 linked with firm-level information from BLADE, the study assesses whether the Trump administration’s tariffs on Chinese goods—intended to restrict China’s role in global value chains—induced Australian firms to diversify away from China or, conversely, deepened their dependence on Chinese inputs. Contrary to expectations of supply-chain risk mitigation and geopolitical hedging, the paper finds that Australian firms with higher pre-existing exposure to tariffed goods increased their import reliance on China in the years following the trade war. These results offer a paradoxical insight: the US-China trade war may have unintentionally reinforced, rather than weakened, Australia’s integration with Chinese manufacturing networks.

The US-China trade war marked a major shock to global production networks. Between 2018 and 2019, the United States raised tariffs on approximately US$350 billion of Chinese imports across multiple lists, lifting the average tariff from 3.7% to 20.8%. China retaliated with duties on US goods, and although Australia did not impose countermeasures, its position as a China-reliant importer made it vulnerable to indirect effects. Australian imports from China are highly concentrated in manufactured goods—the very products most exposed to US tariffs—making Australian firms potential recipients of diverted Chinese exports or incentivising them to find alternative suppliers to hedge rising geopolitical risk. Given renewed waves of US protectionism under the 2025 Trump administration, understanding how Australian firms responded to the earlier shock is timely and policy-relevant.

To identify these effects, the study applies a difference-in-differences strategy exploiting variation across Australian firms in their pre-trade-war exposure to products later targeted by US tariffs. Firms are categorised into treatment and control groups according to the share of their 2017 import basket consisting of tariffed HS-6 products. The analysis compares how these groups adjusted their import values, sourcing patterns, and product variety between 2015–2023. Exposure measures are matched to detailed US tariff line data, and the firm-year dataset incorporates rich controls and fixed effects. This allows the authors to isolate the causal impact of US tariff escalation on Australian import sourcing.

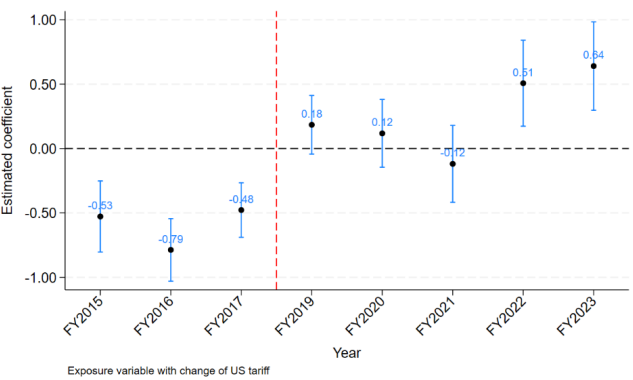

The results reveal a striking pattern: highly exposed Australian firms increased their imports from China in the post-tariff period, particularly in 2022 and 2023 as economic activity normalised after COVID-19 disruptions. At the intensive margin, imports from China rose by an estimated 6.8% relative to less exposed firms, with a shift from the 10th to the 90th percentile of exposure corresponding to an 8.5% increase in imports. This increase appears only after a lag, consistent with international evidence that adjustment to trade shocks occurs gradually as firms re-optimise sourcing contracts and supply chains. In contrast, there is no evidence that exposed firms expanded imports from alternative countries, undermining the hypothesis that geopolitical uncertainty triggered diversification away from China.

The extensive margin results are equally important. Tariff-exposed firms increased the number of distinct products sourced from China, indicating a widening rather than narrowing of product variety linked to Chinese suppliers. This shift occurs earlier than the rise in import values, appearing as early as 2020. Meanwhile, there is no corresponding increase in the number of new products sourced from other countries. These findings highlight an asymmetric pattern: exposure to US tariffs induced firms to expand the breadth and depth of their import relationships with China.

Product-level event-study estimates reinforce these conclusions. For Chinese products directly affected by US tariffs, Australia’s imports exhibit no pre-trend divergence between treated and untreated goods, but post-treatment years show higher values and quantities among treated products. Unit prices do not decline significantly, suggesting that the increase in Australian imports is driven by greater volumes rather than price reductions or dumping behaviour. This aligns with existing literature showing limited price adjustment by Chinese exporters during the trade war and full tariff incidence being passed on to US consumers.

The study also examines heterogeneity across firm characteristics. Large firms and firms with high import dependency were the primary drivers of the increased reliance on China. Small firms exhibited no statistically significant changes, and low-import-dependency firms showed muted or delayed responses. This suggests that firms with greater scale, deeper GVC integration, and more complex input needs were more likely to absorb diverted Chinese exports or deepen China-based supply relationships.

Alternative mechanisms such as roundabout trade—routing Chinese goods via third countries to circumvent tariffs—are unlikely to explain Australia’s patterns due to high transport costs and Australia’s geographical remoteness from the US. Empirical studies confirm that such rerouting mainly occurred through Mexico and Vietnam rather than Australia. Thus, the observed increase in Australian imports from China reflects genuine integration rather than tariff-evasion logistics.

The findings have broader implications for trade policy. While much of the literature emphasises how bystander countries benefit from export-side substitution in trade wars, this paper highlights an understudied form of diversion: increased import-side opportunities for third countries. Australian firms appear to have benefited from greater access to Chinese goods displaced from the US market, despite political tensions and policy discussions around diversification. The results underscore the gap between national-level strategies to reduce dependence on China and firm-level incentives driven by cost, reliability, and existing GVC relationships.

Overall, the paper concludes that the US-China trade war unintentionally intensified Australia’s reliance on Chinese imports. Efforts aimed at encouraging diversification face substantial structural and economic barriers, particularly when firms are embedded in China-centred production networks. The findings highlight the practical limits of decoupling strategies and underscore the need for policymakers to focus on strengthening multilateral frameworks rather than attempting wholesale rerouting of supply chains.