| Author Name | JINJI Naoto (Faculty Fellow, RIETI) / OZAWA Shunya (Kyoto University) |

|---|---|

| Research Project | Comprehensive Research on the Current International Trade/Investment System (pt.VI) |

| Download / Links |

This Non Technical Summary does not constitute part of the above-captioned Discussion Paper but has been prepared for the purpose of providing a bold outline of the paper, based on findings from the analysis for the paper and focusing primarily on their implications for policy. For details of the analysis, read the captioned Discussion Paper. Views expressed in this Non Technical Summary are solely those of the individual author(s), and do not necessarily represent the views of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI).

In the late 2010s, the United States (U.S.) and China initiated a process of decoupling within global supply chains due to political and security concerns. The impact of this decoupling extended beyond the U.S. and China themselves to affect other countries. Decoupling is progressing on a variety of fronts, but an especially controversial issue is the safeguarding by the U.S. and China of their respective technological assets to prevent their unauthorized dissemination to foreign firms. For example, in the U.S., the Export Control Reform Act (ECRA) was enacted in 2018 to regulate the export of technologies that possessed dual-use characteristics, that is, those applicable for both civilian and military purposes. ECRA primarily focuses on technologies within high-tech industries, including artificial intelligence and quantum information technology. Similarly, China imposes restrictions on the export of such technologies through the Foreign Trade Law and Export Control Law. China has also introduced a set of rigorous technology protection policies, notably, the Cyber Security Law and the Data Security Law.

Given these circumstances, this study performs a quantitative analysis of the impacts of technological decoupling between the U.S. and China, coupled with the technology protection policies implemented in both countries on international trade within sectors subject to export control laws, international technology transfers, and the economic welfare of the U.S., China, and other countries. For our analysis, we constructed a model based on a dynamic quantitative general equilibrium model of international trade developed by Anderson et al. (2019). The model developed by Anderson et al., which incorporates the accumulation of physical capital and technology capital, accounts for foreign direct investment (FDI) in the form of technology and intellectual property transfers, allowing for an analysis of international technology transfer restrictions. In this study, we extended their model by introducing a segmentation of output into the intermediate goods sector and the final goods sector. This approach is based on the assumption that only the intermediate goods sector utilizes technology capital and is the main target of technological decoupling and technology protection policies. We calibrated the main parameters of the model based on data from 89 countries for 2016, before technological decoupling was introduced. We then conducted a counterfactual analysis covering several scenarios to quantify the impact of trade and technology transfer restrictions between the U.S. and China, technology protection policies in China, and the export control laws in both countries. We examined the impact of policies in steady state equilibria.

The results of this counterfactual analysis indicated that the economic welfare of the U.S., China, and the world as a whole deteriorates when bilateral decoupling between the U.S. and China, accompanied by related policies, restricts both trade and technology transfer. Moreover, it became clear that China’s technology protection policies have a significant impact, not only on countries that receive substantial technology transfers from China but also on countries that are heavily dependent on technology capital for production. Countries with a higher share of imports from the U.S. and China experienced more substantial declines in the amount of imports of intermediate goods targeted under the bilateral export control policies. However, we also found that the bilateral export control policies did not always lead to a deterioration in economic welfare in third countries, as the decline in imports could be partially supplemented by an increase in domestic output in some countries.

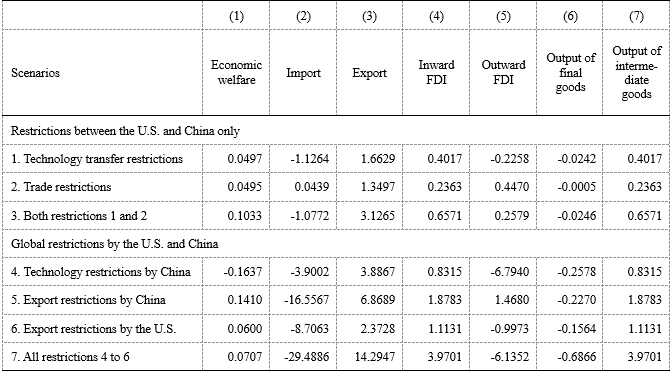

What, then, is the impact on Japan of the technological decoupling between the U.S. and China? The results of the counterfactual analysis conducted for Japan are presented in Table 1. Rows 1 to 3 represent an analysis of scenarios where restrictions are implemented between the U.S. and China only, with row 1 corresponding to restrictions on technology transfer, row 2 corresponding to trade restrictions, and row 3 corresponding to restrictions on both technology transfer and trade. Rows 4 to 7 represent an analysis of scenarios for global restrictions by the U.S. and China, with row 4 corresponding to technology restrictions by China, row 5 corresponding to export restrictions by China, row 6 corresponding to export restrictions by the US, and row 7 corresponding to the implementation of all policies from row 4 to row 6 (Note 1). Columns (1) to (7) represent an analysis of how Japan’s economic welfare, imports and exports in target sectors, inward FDI, outward FDI, and output of final goods and intermediate goods, respectively, change under each scenario. The numbers in the table represent the percentage change in each variable in the steady state equilibrium where restrictions are implemented, compared with the baseline steady state equilibrium where no restrictions are implemented.

Japan’s economic welfare improves, albeit only slightly, if technology transfer, trade, or both are restricted between the U.S. and China only (rows 1, 2, and 3). This can be attributed to an increase in Japan’s exports of intermediate goods and FDI into Japan, as well as an increase in Japan’s domestic intermediate goods output, due to the restrictions on technology transfer and trade between the U.S. and China. Under the scenario where technology transfer from China is restricted by its technology protection policies (row 4), Japan’s economic welfare declines but the welfare loss is only slight, at -0.16%. This result is attributed to China’s relatively small share of Japan’s inward FDI and the relatively low technology capital intensity of intermediate goods production in Japan compared to other countries. If exports from China are restricted by its export control laws (row 5), total imports in the target sectors fall substantially, by 16.6%. This is due to China’s large share of imports into Japan. However, Japan is able to compensate for this decline through an increase in domestic output of intermediate goods. As a result, its economic welfare actually improves. The U.S. export control laws have a qualitatively similar effect, although to a lesser degree than China’s export control laws. Finally, the combined impact of China’s technology protection policies and the export control laws in China and the U.S. leads to a substantial fall in imports in the target sectors (-29.5%), while outward FDI also declines (-6.1%). However, exports and inward FDI in the target sectors actually increase (exports by 14.3% and inward FDI by 3.97%) and economic welfare also increases marginally (0.07%). These results mean that the improvement in welfare through increased domestic output of intermediate goods due to export restrictions imposed by the U.S. and China more than compensates for the welfare losses due to China’s technology transfer restrictions.

As is seen above, Japan may be able to cope with the negative impact of US-China technological decoupling by appropriately adjusting its domestic output of, and investment in, the intermediate goods subject to restrictions. Our counterfactual analysis suggests that Japan does not necessarily sustain welfare losses at least in steady states. However, it may suffer some losses during the transition period, which was outside the scope of our analysis in this study. Negative impacts may also arise through processes that are not anticipated in our analysis. Further analysis is therefore required to assess the real impact of US-China technological decoupling, with paying attention to its future evolution.

- Footnote(s)

-

- ^ This analysis is based on the assumption that the imposition of technology transfer restrictions reduces the access of countries subject to the restrictions to Chinese or U.S. technologies by 80% and that the imposition of export restrictions increases the trade costs associated with exporting intermediate goods from industries subject to the restrictions by 20%.

- Reference(s)

-

- Anderson, J. E., M. Larch, and Y. V. Yotov, 2019. Trade and investment in the global economy: A multi-country dynamic analysis. European Economic Review 120: 103311.