Announcement

The United States adopted a policy of engagement with China during the period between the Nixon administration and the Obama administration, but since the inauguration of the Trump administration, it has come to regard China as a strategic competitor and attempted to halt its rise. To this end, it is promoting a policy of "decoupling," which refers to the severing of the U.S.-China economic relationship through such measures as raising import tariffs on Chinese products, restricting exports of high-tech products to China and strengthening the restrictions on direct investments in the United States by Chinese companies.

In August 2018, a set of laws presumed to be intended to curb the development of the high-tech industry in China was enacted in the United States, and in May 2019, the U.S. government announced a policy that would cut Huawei off from the U.S. market. As indicated by these moves, the trade friction between the U.S. and China is increasingly taking the form of not only a trade war but also a tech war, and the conflict between the two countries is expected to linger on for a long time to come.

Escalating Trade War

The trigger for the ongoing U.S.-China trade friction was the U.S. decision on March 22, 2018 to impose sanctions on China under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974. Following the decision, on April 3, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) announced additional tariffs of 25% on around 1,300 products imported from China worth 50 billion dollars, including high-tech products. In response, on the following day, China expressed its readiness to retaliate by imposing additional tariffs of 25% on 106 items of products imported from the United States, including soybeans and automobiles. In light of what he called "China's unjustified retaliation," President Trump instructed the USTR to consider expanding the range of products subject to additional tariffs. In this way, the U.S.-China trade friction rapidly escalated into a trade war (Figure 1).

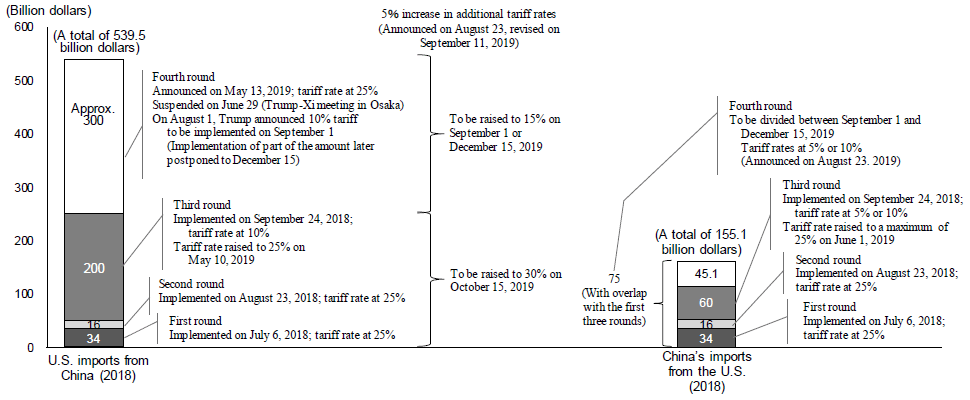

By September 2018, three rounds of additional tariffs had been imposed on each other by both sides. On the one hand, the total U.S. tariffs applied exclusively to China amounted to $250 billion (equivalent to about one half of U.S. imports from China in 2017), with a tariff rate of 25% for the first two rounds (July 6 and August 23, 2018) totaling $50 billion, and 10% (initially scheduled to be raised to 25% by the end of 2018) for the third round (September 24, 2018) amounting to $200 billion. On the other hand, total Chinese tariffs applied exclusively to the U.S. amounted to $110 billion (which is equivalent to about 70% of China's imports from the U.S. in 2017), with a tariff rate of 25% for the first two rounds totaling $50 billion, and 5% or 10% for the third round amounting to $60 billion.

As a major step toward reconciliation, at a meeting between U.S. President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping held on December 1, 2018, on the sidelines of the Group of 20 summit in Buenos Aires, the U.S. gave China a 90-day reprieve (until March 1, 2019) from additional import tariffs. On February 24, 2019, President Trump announced that he would extend the March 1 trade deal truce deadline, citing progress in trade talks, raising the hope that a final deal to end the trade war might soon be forthcoming.

However, this hope evaporated when President Trump suddenly announced on May 5, 2019, a plan to raise the additional tariff rate imposed on the $200 billion of Chinese goods covered by the third round from 10% to 25%, which had been postponed twice, on the grounds that China had backtracked on commitments it made in earlier negotiations. The new tariff hike was implemented on May 10, when high-level economic and trade talks were taking place in Washington DC. China retaliated by announcing on May 13 that it was raising the additional tariff rate on the $60 billion of U.S. goods covered by its third round of tariffs, effective June 1. On the same day, the Office of the USTR released a new list of Chinese imports amounting to about $300 billion that could be subject to a proposed 25% tariff hike (the fourth round). This list covers virtually all remaining imports from China that had not yet been subject to additional tariffs.

Vice Premier Liu He, Beijing's chief negotiator, told a group of reporters after trade talks ended with no deal on May 10 that there were three main points of contention between China and the U.S. (Bloomberg News, 2019). First, the U.S. must remove all the additional tariffs imposed on China. Second, the targets set by the U.S. for Chinese purchases should be in line with real demands. Third, the text of any deal should be "balanced" to ensure the "dignity" of both nations.

In the meeting between U.S. President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping held on June 29, 2019, on the sidelines of Group of 20 summit in Osaka, it was decided that the U.S. would put off its plan to impose additional tariffs on the $300 billion-worth imports from China covered by the fourth round, and high-level trade talks would soon resume. However, the trade war escalated again on August 1, 2019, when President Trump deviated from his promise and announced that additional tariffs of 10% would be imposed on the 300 billion dollars' worth of products imported from China covered by the fourth round from September 1, 2019, although the implementation of some of these new tariffs was later postponed to December 15, 2019. China retaliated by announcing its own fourth round of tariffs covering $75 billion-worth of U.S. goods on August 23, which was followed on the same day by President Trump announcing his plan to add another 5% to the additional tariff rates that apply to the Chinese goods covered by all four rounds of tariffs.

Enactment of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019

What makes things worse is that the dispute between the U.S. and China has spread from issues related to trade to those involving technology. In particular, the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019, signed into law by President Trump on August 13, 2018 contains several important items that aim to sever the links between high-tech industries in the United States and China, including: (1) the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA) of 2018, which strengthens the authority of the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), responsible for reviewing investments in the United States by foreign companies, in order to reinforce the restrictions on investments; (2) the Export Control Reform Act (ECRA), which strengthens export control; and (3) a ban on government procurement of telecommunications equipment made by five Chinese companies (Hirohisa Akahira, "Chokikasuru Beichumasatsu e no Taiosaku wa [How to Deal with the Prolonging U.S.-China Friction]," Japan External Trade Organization, May 15, 2019).

FIRRMA restricts investments by foreign companies in U.S. businesses involving critical technology and infrastructure. This law subjects to review non-passive investments by foreign companies in U.S. businesses involving critical technology and infrastructure and sensitive data, in addition to controlling investments by foreign companies in U.S. businesses, which have already become subjected to review(Note 1). The ECRA, which strengthens export control, provides countermeasures against leaks of critical U.S. technology to foreign countries. Going forward, emerging and foundational technologies, which are not covered by the existing export control, will become subjected to control. In addition, the transfer of emerging and foundational technologies out of the United States and export of products containing a certain proportion of value added by the United States from non-U.S. countries to third countries (re-export) require permission from the Department of Commerce's Bureau of Industry and Security. While the scope of emerging and foundational technologies to be covered by this law has not yet been determined, the following 14 categories of technology have been cited as those that should be considered for inclusion in the scope: (1) biotechnology, (2) artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning technology, (3) position, navigation and timing technology, (4) microprocessor technology, (5) advanced computing technology, (6) data analytics technology, (7) quantum information and sensing technology, (8) logistics technology, (9) additive manufacturing (e.g. 3D printers), (10) robotics, (11) brain-computer interfaces, (12) hypersonics, (13) advanced materials, and (14) Advanced surveillance technologies ("Review of Controls for Certain Emerging Technologies," Federal Register, November 19, 2018). There are substantial overlaps between these technologies and the 10 technology sectors indicated in the "Made in China 2025" plan.

The provision that bans government procurement of telecommunications equipment made by Chinese companies is applicable to the following companies (including affiliates) and products: (1) telecommunications equipment made by Huawei and ZTE, and (2) security video surveillance equipment and telecommunications equipment made by Hytera Communications, Hangzhou Hikvision Digital Technology, and Zhejiang Dahua Technology. The ban is to be introduced in two stages. In the first stage, starting August 2019, U.S. government agencies are prohibited from procuring, acquiring, or using telecommunications equipment and services that use banned products or services as their main components or key technology, and from concluding, extending or renewing contracts for such equipment and services. In the second stage, which will start in August 2020, government agencies will be prohibited from concluding, extending or renewing contracts with companies using telecommunications equipment or services that use banned products or services as their main components or key technology.

The U.S. Ban on Huawei

In order to cut China off from the U.S. high-tech industry, the United States is tightening the restrictions on Huawei, which has a large share in the global market for telecommunications equipment and which is at the forefront of 5G telecommunications technology.

First, on April 17, 2018, the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) decided to prohibit U.S. telecommunications service providers from procuring telecommunications equipment from foreign companies that pose national security risks, with Huawei and ZTE in mind as the targets. In August, the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2019 was enacted, as mentioned earlier. On December 1, Huawei's CFO, Meng Wanzhou, was arrested in Canada at the request of the United States for suspected involvement in financial transactions intended to evade sanctions against Iran.

On May 15, 2019, the US Commerce Department announced that it would add Huawei and 68 affiliates to its Entity List, which comprises individuals and entities subject to specific license requirements for the export, re-export, and/or in-country transfer of specified items. This move in effect bans Huawei from buying parts and components from US companies without US government approval. On the same day, President Trump signed an executive order barring US companies from using telecommunications equipment made by firms posing a national security risk, paving the way for a ban on doing business with Huawei. On August 19, 2019, another 46 affiliates of Huawei were added to the Entity List.

The measures taken by the U.S. government to cut Huawei off from the U.S. market will deal a blow not only to Huawei but also to suppliers around the world, including U.S. companies. Huawei's annual revenue in 2018 amounted to 105 billion dollars, while the company spent 70 billion dollars for component procurement from outside sources. Of the 70 billion dollars, around 11 billion dollars went to U.S. companies, including Qualcomm, Intel and Micron Technology. ("Huawei's $105 billion business at stake after U.S. broadside," Reuters, May 18, 2019). The restrictions on transactions with Huawei pose such risks as the shrinkage of the market and a decline in corporate earnings in the U.S. semiconductor industry. Due to concerns over the risks, in the U.S. stock market, prices of high-tech stocks and semiconductor-related stocks which supply Huawei in particular, suffered sharp falls following the May 15 announcements.

Expansion and Deepening of the Tech War

The United States is not only trying to cut Huawei off from its market but also calling on its allies to follow suit (Stu Woo and Kate O' Keeffe, "Washington Asks Allies to Drop Huawei," The Wall Street Journal, November 23, 2018). For the moment, a handful of countries, including Japan, Australia and New Zealand, have joined the United States in the effort to ostracize Huawei.

In Japan's case, on May 27, 2019, the government announced the strengthening of the restrictions on foreign investments in Japanese companies as a way to prevent leakage of critical information and technology outside the country. Specifically, for national security reasons, the government will add 20 business sectors related to IT and telecommunications to the list of businesses for which notice is required before they receive foreign investments, starting in August. Back in December 2018, the government revised its procurement policy concerning information and communications equipment with a view to excluding Huawei products from the Japanese market ("Japan to Add 20 Business Sectors Related to IT and Telecommunications to Foreign Investment Restriction List," Mainichi Shimbun, May 27, 2019).

Huawei is not the only Chinese company subjected to a U.S. export ban. ZTE was added to the Entity List and was kept on it from March 2016 to March 2017 for exporting goods to Iran and North Korea in violation of U.S. sanctions (Note 2). Subsequently, many Chinese entities (mostly companies and research institutions) engaged in space development, semiconductor and supercomputer businesses have been added to the Entity List. Among those enterprises are Sugon, which is China's leading supercomputer maker, and Tianjin Haiguang Advanced Technology Investment Company, which had formed a joint venture with Advanced Micro Devices, a major U.S. semiconductor maker (both of these Chinese companies were added to the Entity List in June 2019).

Meanwhile, in U.S. policy circles, moves reminiscent of the Red Scare, which advocated the purge of communism, are starting to spread (Anjani Trivedi, "China could win from tech Cold War," Bloomberg, April 30, 2019). Specifically, the moves include the strengthening of universities' screening of research proposals from China, delays in the issuance of visas for Chinese scientists planning to visit the United States to attend conferences or participate in exchange programs, and the shortening of the visa period for Chinese graduate school students studying robotics and other advanced manufacturing industry technology from five years to one year. The M.D. Anderson Cancer Center in Houston dismissed three senior researchers of Chinese ethnicity when the U.S National Institutes of Health determined that those researchers had potentially violated disclosure and confidentiality rules. Employees at various technology companies have been charged with stealing trade secrets.

In response to these offensive moves by the U.S., in addition to raising tariffs on imports from the U.S., the Chinese side has started to explore other retaliatory measures.

First, China is gearing up to use its dominance of rare earths to hit back. Shortly after President Xi's visit to a rare earth firm, a flurry of Chinese media reports in late May 2019, including a column in the People's Daily on May 29, raised the prospect of Beijing cutting exports of rare earths that are critical in the defense, energy, electronics, and automobile sectors.

Second, on May 31, 2019, China announced that it will establish its own "list of unreliable entities" based on relevant laws and regulations. Foreign enterprises, organizations and individuals that do not comply with market rules, violate the spirit of contracts, block, or cut supplies to Chinese firms for noncommercial purposes, and seriously damage the legitimate rights and interests of Chinese enterprises, will be added to the list of unreliable entities.

Third, the Xinhua News Agency reported on June 8, 2019, that China's National Development and Reform Commission has been tasked with organizing a study on establishing a national technological security management list system, with the aim of more effectively forestalling and defusing national security risks ("China to establish national technological security management list system").

While these new "weapons" may enhance China's bargaining power when negotiating with the U.S. on one hand, they may also become new sources of friction between the two countries.

A War with No Winner

The escalating U.S.-China trade friction is casting a cloud not only over the U.S. and Chinese economies, but also over the global economy as a whole.

In China, foreign companies' moves to transfer production out of the country are accelerating as extensive restrictions have been imposed on trade with the United States. In addition, it is becoming increasingly difficult for Chinese companies and investment funds to invest in U.S. companies, particularly in the high-tech sector, as a result of the strengthening of the restrictions on foreign investments in the United States. Indeed, the value of Chinese direct investments in the United States fell from 46 billion dollars in 2016 to 29 billion dollars in 2017 and to 4.8 billion dollars in 2018 (Thilo Hanemann, Cassie Gao, and Adam Lysenko, "Net Negative: Chinese Investment in the US in 2018," Rhodium Group, January 13, 2019). In response to the U.S. policy of decoupling, China is seeking to strengthen relationships with developing countries that keep the United States at arm's length, mainly through the Belt and Road Initiative, while enhancing its own technology development capabilities. Even so, given the constraints imposed on resource allocations and market size in addition to the difficulty of acquiring foreign technology, it is inevitable that the Chinese economy's growth rate will decline.

On the other hand, the United States must also be prepared to pay a high cost for promoting the policy of decoupling. China is not only the world's second largest economy but also the core of global supply chains. In addition to final consumption goods, intermediate goods such as parts and components make up a large share of U.S. trade with China and the production of U.S. companies in China. With restrictions on doing business with China becoming increasingly severe, more and more U.S. companies will have to move their operations from China to other countries at the expense of efficiency. As a result, the U.S. will not only lose its market share in China, but will also have to import from more expensive sources. Indeed, due to concerns over this risk, major U.S. technology companies, including Apple, HP, Dell, Microsoft and Intel, issued statements (HP, Dell, Microsoft and Intel issued joint comments) that opposed the imposition of tariffs and coincided with the convening of public hearings related to the fourth round of additional tariffs from June 17, 2019.

If the restrictions on flows of people, goods, capital and technology between the United States and China are strengthened and the decoupling of the two countries' economies proceeds further, the global economy could be divided into two blocs centered on the United States and China, respectively. In that case, multinationals could no longer optimize the allocation of resources by investing globally, and supply chains would have to be reshaped to adapt to this new environment. The negative impact on global trade and investment, as well as economic growth, may far exceed that of the United Kingdom's withdrawal from the European Union. An early settlement of the ongoing trade war between China and the U.S. is needed to avoid this worst-case scenario.

Information

- Time and Date: 13:00-15:00, Thursday, July 18, 2019

- Venue: RIETI's seminar room (METI Annex 11th floor, 1121), 1-3-1

Kasumigaseki, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo - Language: Japanese

- Admission: Free

- Capacity: 100

- Host: Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI)

Speakers

Panelists (in order of appearance):

- KAWAGUCHI Daiji (Professor, Graduate School of Public Policy, University of Tokyo)

- MIYAJIMA Hideaki (Faculty Fellow, RIETI / Executive Vice President for Financial Affairs, Waseda University / Professor, Graduate School of Commerce, Waseda University / Adviser, Waseda Institute for Advanced Study)

Moderator:

- NAKAJIMA Atsushi (Chairman, RIETI)