| Author Name | Willem THORBECKE (Senior Fellow, RIETI) |

|---|---|

| Research Project | Economic Shocks, the Japanese and World Economies, and Possible Policy Responses |

| Download / Links |

This Non Technical Summary does not constitute part of the above-captioned Discussion Paper but has been prepared for the purpose of providing a bold outline of the paper, based on findings from the analysis for the paper and focusing primarily on their implications for policy. For details of the analysis, read the captioned Discussion Paper. Views expressed in this Non Technical Summary are solely those of the individual author(s), and do not necessarily represent the views of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI).

The Indonesian economy has a long history of steady growth punctuated by times of turmoil and crisis. Recently Indonesia has faced the COVID-19 pandemic, inflation, contractionary U.S. monetary policy, and fluctuating commodity prices. To examine how the economy is faring since the pandemic began, this paper compares sectoral stock returns since COVID-19 hit the Indonesian economy with forecasted returns based on macroeconomic variables.

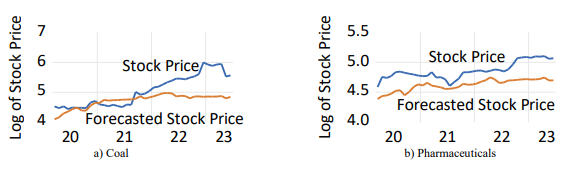

The results indicate that, since COVID hit and commodity prices have risen, coal and iron and steel firms have done well. In addition, sectors that gained from the pandemic such as pharmaceuticals and health care continue to outperform. Telecommunications equipment stocks soared as people working from home upgraded their information and communications technology (ICT) equipment. Banks and the financial sector, after underperforming when the pandemic struck, are now behaving as predicted by the macroeconomic variables. Bank stocks have risen 50% since the pandemic began. Non-commodity manufacturing firms and sectors related to construction are performing badly. Figure 1 shows how the coal and the pharmaceutical sectors have fared since the pandemic began.

The findings also indicate that Indonesian sectors are especially exposed to the aggregate Indonesian stock market. Their independent exposures to other variables such as exchange rates and world demand are small. This is what would be expected of an economy whose growth is driven by domestic demand rather than net exports.

Indonesia has a large domestic market with more than 277 million consumers. Many firms depend on this for their profitability. In addition, the findings indicate that coal, iron and steel, and natural resource sectors have performed well.

Previous experience indicates that the Indonesian domestic economy can suffer sudden downturns as it did during the 1997-1998 Asian Financial Crisis (AFC). History also indicates that commodity booms can give way to commodity busts. For instance, crude oil prices increased tenfold between 1973 and 1981 as the OPEC cartel, the Iranian revolution, and other factors restricted supply. Oil prices then collapsed between 1981 and 1986 as an oil glut emerged.

It would be beneficial for Indonesia to diversify by having another possible growth engine. A natural candidate would be labor-intensive manufactures. After oil prices collapsed in the 1980s, Indonesia turned to exporting textiles, shoes, furniture, and other labor-intensive goods. As Indonesia competed in world markets, it was forced to improve quality and lower prices (Yoshitomi, 2003). If Indonesia today could increase its exports of labor-intensive goods, the discipline of competing in world markets would once again raise productivity. The World Bank (2023) has noted that low growth of labor productivity and total factor productivity has plagued the Indonesian economy.

Indonesia before the AFC succeeded in exporting labor-intensive goods by attracting FDI from MNCs. FDI acted as a vehicle for transplanting superior production technology to Indonesia. Vietnam currently is succeeding by attracting export-oriented FDI. How can Indonesia attract FDI from MNCs participating in regional value chains?

One key step to attract FDI would be to improve education and human capital formation. Indonesia ranked 71st out of 78 countries in the 2018 Programme for International Assessment (PISA) tests of the educational attainment of 15-year-olds in math, science, and reading. The World Bank (2023), examining student performance on standardized tests, found that fourth grade Indonesian students lost on average 11 months of skills, with the losses greater for poorer students and for students who rarely use the internet. The Indonesian government should allocate funds for educational recovery, increase school hours and remedial training, and enlist parents to help students learn more outside of classroom hours. Japan, Australia, and other countries should consider providing Official Development Assistance to help in these areas and to help vulnerable children obtain good prenatal care, nutrition, and healthcare in their early years.

A second key step to attract FDI would be to resist protectionism. The Global Trade Alert reported that Indonesia enacted 532 protectionist trade interventions between January 2009 and January 2022, more than twice as many as Malaysia did and more than four times as many as Thailand did over the same period. As Cali and Montfaucon (2021) discussed, protectionist measures include import approvals, restrictions on the port of entry for imports, pre-shipment inspections, and mandatory certification with the Indonesian national standard. Since Indonesian exporters depend on imported inputs, restrictions on imports can reduce exports.

Cali and Montfaucon (2021) provided evidence of the deleterious effect of import restrictions on exports. They investigated monthly exports from all firms over the 2014 to 2018 sample period. They reported that a 1% increase in restrictions on port of entry for imports or mandatory certification with the Indonesian national standard reduces both the volume and value of exports by almost 1%. They also noted that nontariff measures that shield Indonesian firms from import competition make them less productive. They reported evidence of drops in the number of export destinations, the probability of firm survival, and the extensive margin of exports for firms in protected sectors. Protectionism thus darkens the atmosphere for exporters and deters foreign investors.

The Indonesian economy is performing well, driven by domestic demand and natural resource exports. Experience during the AFC and the collapse of oil prices in the 1980s indicates that both of these engines of growth can seize up. Nurturing labor-intensive exports as a third engine could increase the robustness of the Indonesian economy and raise productivity.

- Reference(s)

-

- Cali, M., Montfaucon, A., 2021. Non-tariff measures, import competition, and exports. (Policy Research Working Paper 9801). World Bank, Washington DC.

- Yoshitomi, M. 2003. Post-Crisis Development Paradigms for Asia. Asian Development Bank Institute, Tokyo.

- World Bank, 2023. The invisible toll of COVID-19 on learning. Indonesian economic prospect, June. World Bank, Washington DC.