“Let me begin with a philosophical point. Just as we speak of the “Global South,” I would like to propose the term “Global West.” What matters is not where a country is located geographically, but how its economy and industries are interconnected.”

—Dr. Gerhard Wahlers, Deputy Secretary General, Konrad Adenauer Stiftung (Berlin Headquarters)

The year 2025 marked the advent of new government administrations in both Germany and Japan. Although both countries are core members of the G7, technological development is advancing at a rapid pace, and the security environment is becoming increasingly severe. Like two vessels navigating rough seas, both now face difficult decisions regarding the course they must set.

During his recent visit to Japan, Dr. Gerhard Wahlers, Deputy Secretary General of the Berlin Headquarters of the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, a German political foundation, graciously took time out of his demanding schedule—meetings with policymakers across ministries, a visit to Yokosuka, and more—to visit the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) on 4 November. During the visit, he shared with participants a renewed framework for understanding today’s international politics.

Through the insights of Dr. Wahlers—who has known Chancellor Friedrich Merz for a quarter of a century—I was able to deepen my own understanding of the situation surrounding Germany today and gain valuable hints that aid in thinking about the future direction of Japan–Germany relations.

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. Wahlers for making the long journey to Japan, and to the Japan Office of the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung for their generous support in organizing the discussions.

How is it different from the “Western Bloc”?

Dr. Wahlers’ opening remarks drew appreciative nods from the Chairman and the policymakers present. I was also impressed. Yet later that evening, I found myself wondering: How is the “Global West” (Globaler Westen) actually different from the “Western Bloc” (Der Westen)?

Why did everyone perceive the “Global West” as such a fresh and striking concept?

Two factors likely contributed to this sense of newness:

1. It invites comparison with the Japanese government’s own foreign policy framework regarding the “Global South.”

2. It emerged at a moment when the United States is undergoing remarkable changes, prompting the search for a new term that could describe a community of like-minded countries.

These two factors together may explain why the term felt new and resonant.

(1) Comparison with the “Global South”

The Japanese government has emphasized the importance of cooperating and co-creating with the “Global South”—a term referring to emerging and developing regions facing vulnerabilities and social challenges (Note 1). But looked at critically, any category prefixed with “Global XX” in a geopolitical context tends to imply vulnerability.

Being labeled as part of the “Global West” thus compels Japan and Germany alike to reflect on the fact that they, too, face vulnerabilities and challenges, just like the countries grouped under the “Global South.”

Moreover, just as the “Global South” clearly does not literally mean countries in the southern hemisphere, the “Global West” is not limited to Europe and North America. That makes it a concept Japan can more comfortably adopt as a marker of its own identity.

(2) A new way to express a community of like-minded partners

The year 2025 saw the imposition of “Trump tariffs” and direct U.S.–Russia ceasefire negotiations over Ukraine—developments unimaginable under the previous Biden administration, and which caused deep unease in Europe and Japan. As the United States, long the unshakable leader of the “Western Bloc” during and after the Cold War, undergoes significant change, Germany has come to rely more heavily on partnerships with like-minded countries across the geographically distant Asia–Pacific: Japan, South Korea, and Australia. The same holds true in terms of Japan’s perspective toward Europe.

The “Global West,” grounded in a rhetoric reminiscent of “Ich bin ein Berliner”—that those who share values are part of the same community regardless of geography—offers a way to articulate one’s international stance without being unsettled by the rapid transformations of major powers.

So, what challenges do Germany and Japan face—as two countries belonging to this “Global West”? And on the basis of which shared values can the two deepen their cooperation? Let us first discuss the remarks made by Dr. Wahlers, then consider the realities of Japan–Germany trade and an example from the history of bilateral cooperation.

Key Theme 1: Security

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has had a profound impact on the security of Germany and Europe as a whole. The pressing current challenge is how to secure a sustainable security framework for the future—and how to finance it—in other words, this is an obligation that cannot be avoided. For this reason, this year Germany amended its Basic Law (equivalent to its constitution) to lift the “debt brake” rule (which limited new government borrowing to 0.35% of GDP), thereby allowing for €500 billion in new borrowing to be used for defense and related purposes.

As Dr. Wahlers first pointed out, the severe security environment that Germany has faced for many years has become a major theme. Most recently, concerns have grown over possible Russian attacks on NATO’s eastern member states, following the discovery in Poland of a combat drone suspected of being deployed with deliberate Russian involvement.

On the other hand, one of the most debated topics within Germany today is the question of conscription. Although Germany abolished conscription in 2011, the current security environment has led to renewed discussion, based on the concern that voluntary enlistment alone may not be sufficient to maintain the Bundeswehr at the necessary scale. Recently, some members from both the governing and opposition parties have proposed that in years when the number of volunteers is insufficient, a number of young people of eligible age be selected by lottery for compulsory service.

However, a majority of the public does not support this lottery-based system. Defense Minister Boris Pistorius has also expressed caution toward any measure that would compel people into service involuntarily, emphasizing that the Bundeswehr can be sustained through voluntary enlistment and that any changes must follow parliamentary debate and statutory procedures (Note 3).

At the same time, as shown in Figure 2, public opinion polls indicate substantial support for introducing conscription for both men and women—a position that exceeds the share of those who oppose reinstating conscription altogether. This is a point that deserves close attention.

Key Theme 2: The Economy

Germany continues to position itself as a leading actor in economic policy. The country maintains a strong presence in basic research, supported by a well-developed research environment. European nations likewise recognize Germany’s importance both politically and economically and continue to hold high expectations for its leadership.

Next, with regard to the theme of the economy raised by Dr. Wahlers, as noted above, Europe continues to expect Germany to play a leading role in driving economic growth.

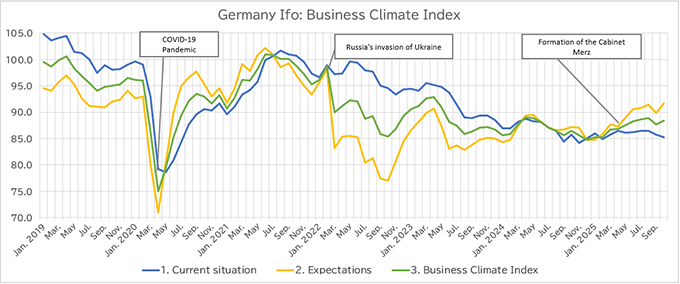

Although the German economy suffered damage from the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, business sentiment has improved since the inauguration of the Merz cabinet. Surveys of corporate assessments of current conditions and future prospects show a spreading expectation of gradual recovery. As Dr. Wahlers highlighted, Europe continues to look to Germany for economic leadership.

[Click to enlarge]

Of course, Germany also faces challenges:

- Export procedures remain overly complex and must be streamlined;

- Energy prices—an essential factor for industrial competitiveness—must be stabilized at competitive levels;

- And although the United States is an indispensable export market for German products, under the Trump administration, the conditions for entering the U.S. market have become opaque, creating potential negative pressure not only for Germany but also for Japan.

Naturally, Dr. Wahlers did not overlook these challenges. The Merz administration has identified the dismantling of bureaucratic red tape (Bürokratie) as a core issue, as well as the need to address the surge in LNG prices—exacerbated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine—which has a direct impact on household and industrial energy costs.

As he emphasized, the United States remains Germany’s largest export destination outside the EU. According to the latest statistical data, the value of German exports to the United States in September 2025 amounted to €12.2 billion, an increase of 11.2% from the previous month (Note 6). Although total exports from January to September were 7.4% lower than in the same period in 2024—likely due to the Trump tariffs—the volume remains nearly double that of exports to other major non-EU partners such as China and the United Kingdom. The United States thus remains economically indispensable for Germany.

Free trade—not localization—is decisively important for Germany. The reason is simple: Germany currently depends on exports. In that sense, Germany will not always share the same views as France, whose economic structure differs. Politicians should not be reinforcing “Made in Europe.”

Dr. Wahlers expressed concern over growing trends toward localization and emphasized the necessity of free trade for Germany.

The “Made in Europe” initiative referenced above is a new EU industrial policy proposal aimed at strengthening competitiveness. It has been strongly advocated within the EU, and particularly by the French government, including President Emmanuel Macron (Note 8) and former European Commissioner (Internal Market) Thierry Breton (Note 9). One of its strategic pillars includes reducing dependence on supply chains from non-EU countries, giving the initiative a distinctly localization-oriented character.

By contrast, in July 2025 Chancellor Merz announced the German government initiative “Made for Germany,” which provides investment support for more than 60 companies ranging from startups to large enterprises for the establishment of new business sites, research and development, and modernization of infrastructure within Germany (Note 10). While this initiative encourages increased domestic investment, it does not, in the context of supply chains, promote localization or the reduction of dependence on specific foreign countries in the same way as the “Made in Europe” strategy.

Considering that Japan—a trade-dependent nation—recorded exports totaling 9.1856 trillion yen in September 2025 (preliminary figures) (Note 11), and that Germany exported €131.1 billion (over 20 trillion-yen equivalent (Note 12)) in the same month, it is clear that exports are likewise a crucial engine of German economic growth. Although Germany differs from Japan in that a substantial portion of its exports go to other EU member states, for Germany, a free-trade regime remains the driver of the economy. Truly, this was one of Dr. Wahlers’ most insightful remarks.

Key Theme 3: Economic Security

Germany has traditionally built its security posture on a close relationship with the United States. German reunification (Wiedervereinigung), for example, would not have been possible without U.S. support. Yet in recent years, the Germany–U.S. relationship appears to have shifted from one grounded in shared values to one increasingly characterized by transactional dynamics.

Germany’s economic dependence on China also represents a vulnerability in terms of supply chain resilience.

The final theme raised by Dr. Wahlers, which led to the most animated discussion among participants, was economic security.

He began by addressing the United States. Looking back, the Trump administration’s April 2025 announcement of broad tariff increases on countries around the world sent shockwaves through both the EU and Germany. During his visit to Washington in June, Chancellor Merz presented President Trump with a 19th-century family registry certificate related to the Trump family, and expressed gratitude for the United States’ role in liberating Germany from Nazi rule 80 years ago. Merz later recounted that these gestures helped open the conversation, which led to what he labeled a “good meeting” (Note 13) on the situation in Ukraine, economic matters, and trade. In July, the EU also reached an agreement with the United States regarding tariff measures (Note 14).

Nevertheless, President Trump has continued to state that “our allies have taken advantage of us on trade more than China did,” (Note 15) suggesting that tensions between the United States and Germany are unlikely to be fully resolved in the near future.

Regarding China, the governing coalition agreement between the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), the Christian Social Union (CSU), and the Social Democratic Party (SPD) clearly stipulates that Germany will take a firm stance toward China whenever necessary. The agreement states (Note 16):

“We must acknowledge that China’s behavior has increasingly brought the aspect of ‘systemic rivalry’ to the forefront. In view of this situation, we will reduce unilateral dependencies, advance a ‘de-risking’ policy, and strengthen resilience. When necessary, Germany will face China with confidence and its own capabilities. Achieving this requires a coherent and closely coordinated China policy within the EU and with other partners.”

China continues to hold a prominent position as a source of German imports. For instance, according to German trade statistics for January–September 2025, imports from China accounted for more than 10 percent of Germany’s total imports—an increase of nearly 10 percent compared to the same period in 2024 (Note 17). While Germany’s policy does not aim to reduce the overall volume of trade with China, the German economy can no longer be discussed without considering the relationship with China.

Within those import statistics, dependence on China is particularly pronounced in materials essential for economic security.

Just last month, Norbert Röttgen—Deputy Chair of the CDU/CSU parliamentary group responsible for foreign affairs—criticized Germany’s dependence on China for semiconductor supply chains. His comments highlight the high level of interest within the governing parties in relation to matters of economic security (Note 19).

Rare earth elements, another category of strategically essential materials, also reveal an important pattern in the data.

As shown in Figure 6, prices suggest an apparent rise in imports from within Europe. However, this increase is often attributed to Europe serving merely as a transit hub (Note 20). About two-thirds of the total weight of all rare earths imported into Germany arrive directly from China, and the linear trend line remains positive—indicating that rising import prices from Europe do not necessarily reflect any decline in structural dependence on China. Rather, supply chains that appear on the surface to be formed within the European region are, when traced upstream to their sources of origin, presumed to ultimately lead back to China.

In October 2025, China’s Ministry of Commerce announced the implementation of export controls on rare earth raw materials—such as those illustrated in Figure 6 (Note 21)—as well as rare-earth-related equipment and auxiliary materials. After the late-October U.S.–China summit, Beijing announced that these measures would be suspended until 10 November 2026, temporarily easing tensions. Even so, given the high Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) associated with rare earths—indicating heavy reliance on a single supplier—rare earths will remain a structural weak point in Germany’s economic security.

In designing economic security policy, it is essential to analyze trade statistics—especially import data—not only in value terms but also in terms of physical quantities. Prices reflect only short-term market fluctuations, whereas assessing supply disruption risks requires understanding the structure of quantitative dependence. For this reason, policy priorities often shift from procuring items at the lowest cost, to securing sufficient quantities and diversifying supply sources.

Interim Summary: The Need for a Risk-Taking Mindset

I am concerned about the issue of uncertainty. German society, he noted, is relatively homogeneous and generally averse to taking risks. In politics as well, compromise tends to prevail. German citizens, too, are insufficiently prepared in terms of assuming risk. Moving forward, what matters is how effectively risks can be factored in and managed.

- → In this regard, artificial intelligence (AI) is considered by Germans society as posing particularly high risks. Although the German research environment for AI is well developed, AI development is not widely welcomed. The regulatory trajectory for the coming years will therefore become highly significant.

In the fields of security, the economy, and economic security, where the two intersect, bold risk-taking at the societal level is sometimes necessary. Yet Dr. Wahlers warned that Germany lacks the social conditions necessary to take such risks, citing AI as an illustrative example.

Although more than 80 percent of the German population now uses AI in some form, surveys show that one-third of employees fear AI will negatively affect their own jobs (Note 23). Professor Ludger Wößmann of Ludwig Maximilian University Munich, who also heads the Ifo Institute for the Economics of Education, argues that navigating societal transformation is particularly difficult in an aging Germany and that even highly skilled professions, such as programmers and legal experts, face the risk of being substituted by AI (Note 24). To adapt, individuals must possess strong foundational skills in language, mathematics, and the natural sciences, as well as adaptability, problem-solving ability, and creativity. He underscores the need to establish robust lifelong-learning frameworks (Note 25).

(In response to the question—raised with reference to Japan’s Growth Strategy Council—of what kind of growth strategy Germany possesses,) Germany does not need theoretical or abstract growth; it needs real, concrete growth. The urgent task is to remove various risks and identify the sectors in which genuine growth is possible.

Rephrased, his message is this: responses to risk must ultimately be judged by whether they contribute to realistic, tangible economic growth.

Debates on advanced technologies or highly divisive issues often degenerate into ideological disputes. In both economic and security policy, realizing visions and ideologies easily become confused with actual policy objectives. Because ideological positions provide a clear sense of moral “rightness,” they also enable people to justify public hostility or online abuse without hesitation. What is needed—by policymakers, business leaders, and society at large—is a sustained focus on what actions truly enhance citizens’ well-being, particularly in measurable and concrete terms.

The Advent of Japan’s New Administration

Having examined Dr. Wahlers’ views and the context surrounding Germany’s major policy themes, it is worth noting that Japan, too, saw a new administration take office in October 2025—one that places priority on many of the same issues.

On 4 October, Sanae Takaichi was elected president of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). However, on 10 October, Komeito announced its departure from the coalition, and with U.S. President Trump reportedly preparing for a visit to Japan later that month, intense negotiations unfolded among parties in order to obtain sufficient votes in the Diet for the prime ministerial designation. Ultimately, the LDP concluded a coalition agreement with the Japan Innovation Party (Ishin), and—although Ishin did not secure ministerial posts—the two-party coalition enabled the inauguration of the Takaichi Cabinet on 21 October. While the coalition agreement lacks the extensive detail typically found in German coalition accords (Note 26), it nonetheless outlines core principles in areas including economic and fiscal policy, foreign and security policy, and economic security policy (Note 27).

The international media widely reported the inauguration of Japan’s first female prime minister. Dr. Wahlers too, expressed interest in how the new administration would position itself—especially regarding relations with the United States. Before assessing Japan’s policy direction, however, it is important to consider how Germany’s media reported on the rise of the Takaichi administration. The following section highlights particularly notable references from German coverage of the new coalition.

As reported by ARD, the method of explaining the dissolution of the LDP–Komeito coalition to a German audience—by comparing it to the CDU parting ways with its sister party, the CSU—is particularly striking. In a country where coalition governments are the norm, such an analogy is both accessible and effective.

More noteworthy, however, is the way German media portrayed the political orientation of Takaichi and Ishin. Many in Japan might be at least somewhat surprised by the framing. Takaichi was described as a “nationalist hardliner and ultraconservative” (Nationale Hardlinerin und ultrakonservativ), with her positions on same-sex marriage and the use of maiden names after marriage cited as examples emphasizing her conservative profile. In addition, both ZDF and DW referred to Ishin as right-wing (rechtsgerichteten), a characterization that likely shaped German public perception of Ishin’s political identity. At the same time, these outlets also highlighted the challenges Japan faces—such as rising living costs and pressures on social-security systems—indicating that the foundations of the new coalition are far from stable.

Future Germany–Japan Relations

Japan faces challenges similar to Germany in the areas of national security, economic competitiveness, and economic security. The semiconductor sector, for example, offers a particularly promising field for bilateral cooperation between Germany and Japan.

As Dr. Wahlers emphasized, both countries share the issues outlined throughout this paper, and for that reason, enhanced cooperation between Japan and Germany can yield mutual benefits. The policy instructions issued by Prime Minister Takaichi to her cabinet outline initiatives such as promoting a Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) and strengthening cooperation with allied and like-minded countries—priorities that closely align with those of the Merz government in Germany.

At the Japan–Germany Summit Meeting in June 2025, the two leaders exchanged views on U.S. tariff measures, economic issues, nuclear and missile challenges, the Indo-Pacific, and the situation in Ukraine. They agreed to further strengthen cooperation on national security and economic security (Note 30). In August, then-Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry Yoji Muto met with Foreign Minister Johann Wadephul and accompanying German business leaders in Germany. They exchanged views on supply-chain resilience, the importance of a rules-based economic order, and the potential for future bilateral cooperation—confirming that both countries would continue close coordination going forward (Note 31).

A particularly important development in the field of economic security was the launch in 2024 of the Japan–Germany Economic Security Consultation Framework, established under the former Kishida and Scholz administrations. Under this framework, Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry co-chaired meetings with Germany’s Federal Foreign Office and, depending on the session, the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action or the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy. Two rounds of consultations were held—in November 2024 and October 2025. Recognizing the importance of cooperation between Japan and Germany, which share similar industrial structures and advanced technological capabilities, both sides exchanged views on key issues such as supply-chain resilience, responses to non-market policies and resulting overcapacity, countering economic coercion, and the protection and development of critical and emerging technologies. They agreed to deepen bilateral cooperation, including through the exchange of specialized expertise in economic security (Note 32).

As noted above, there was significant variety in the commentary on the inauguration of the new Takaichi administration. Nonetheless, its foreign-policy stance largely follows that of the previous Ishiba administration, and Japan–Germany relations are expected to deepen further.

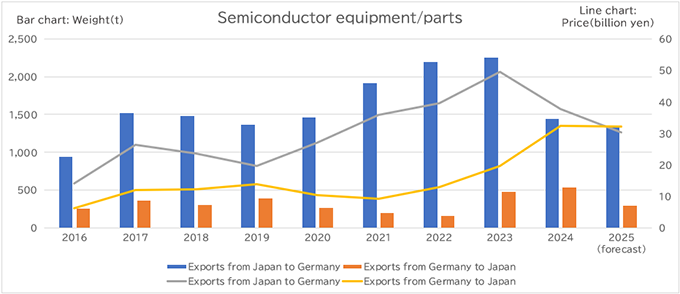

At this point, let us look at one example of Japan–Germany trade patterns concerning strategically important materials for economic security, illustrated in Figure 7.

[Click to enlarge]

[Click to enlarge]

In terms of volume, semiconductor-related equipment and components are exported in larger quantities from Japan to Germany. In terms of value, however, German exports to Japan have now reached a level comparable to Japan’s exports to Germany. In recent years, against the backdrop of a weaker yen and stronger euro, the rising trend in prices of semiconductor-related equipment and components exported from Germany to Japan has become markedly more pronounced compared with the increase in quantities.

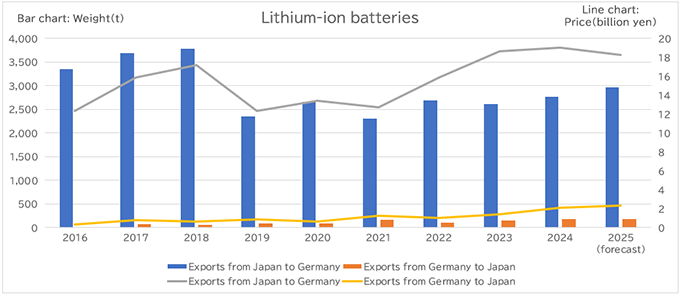

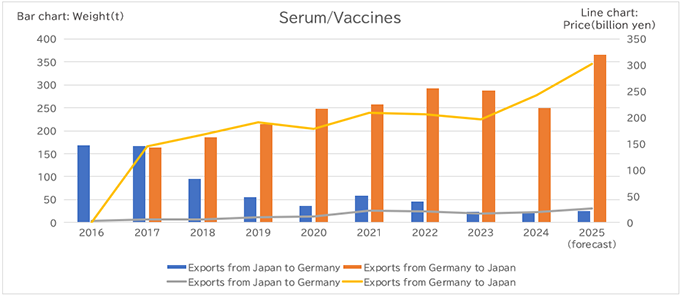

Lithium-ion batteries, by contrast, are exported primarily from Japan to Germany, whereas Germany overwhelmingly exports serum and vaccines to Japan. As noted earlier, due to exchange-rate fluctuations, the growth in value has been more modest than the growth in volume for Japan’s lithium-ion battery exports to Germany, while the opposite is true for Germany’s serum and vaccine exports to Japan, where the increase in value has been particularly steep.

In short, Japan and Germany exhibit differing strengths when it comes to high-tech strategic goods. Although the two countries compete in many industrial areas—most prominently automotive manufacturing—in the context of economic security they may be seen as complementary in certain strategic domains. As Dr. Wahlers noted, this suggests room for further development of policy frameworks that facilitate deeper bilateral cooperation.

That said, ignoring China—Japan and Germany’s major trading partner—would be akin to “missing the forest for the trees.” Understanding the wider forest also helps illuminate the characteristics of Japan–Germany trade.

As an example, let us examine Germany’s import profile for lithium-ion batteries.

As readers might expect, Germany’s import volume from China far exceeds that from Japan. It is therefore difficult to argue that Japan could replace China as a core supplier in Germany’s lithium-ion battery supply chain.

What warrants particular attention, however, is the euro price per ton—an indicator that reflects product value-added characteristics. The data show that Japan’s per-ton export price is roughly double that of China. This strongly suggests that the lithium-ion batteries exported from Japan are qualitatively distinct, occupying a significantly higher price bracket than Chinese products. If this is the case, China would not be able to fully and immediately displace Japan in its exports to Germany. For example, while China primarily exports large volumes of lithium-ion batteries for use in EV onboard systems, Japan may be exporting mainly high–value-added lithium-ion batteries for use in compact IT devices. At the very least, one may reasonably conclude that Japan occupies a unique and differentiated position within Germany’s lithium-ion battery supply chain.

Learning from History

Having reviewed various data on the current situation, it is worth considering, finally, what policy options Japan and Germany might pursue to strengthen cooperation in the field of economic security.

To explore this question, let us once again turn the clock back to an earlier period.

In the more than 150 years of Japan–Germany relations, the period in which the international environment was most severe for both countries—and the period during which they sought economic cooperation as two of the very few partners available to one another—was likely the Second World War, which ended 80 years ago.

In 1937, the Anti-Comintern Pact between Japan and Germany evolved into the Tripartite Pact with Italy in 1940, which solidified the international political structure of the Axis powers opposing the Allied nations such as the United States and the United Kingdom. As the fronts expanded with the outbreak of the German–Soviet War and the War against the United States, the two countries sought to strengthen the supply of military materials and technical cooperation, and on 20 January 1943, they concluded the Japan–Germany Economic Cooperation Agreement (Note 35). Although the text of the agreement itself remained highly abstract, declaring general economic cooperation, an annex titled the “Agreement between Japan and Germany on Technical Cooperation” (Note 36) was also concluded. This annex set forth mutual provisions on the transfer of patents, supply of machinery and equipment, dispatch of engineers and scientists, facilitation of technical training, and preferential treatment for industrial investment applications in each other’s territories.

Japan requested machine tools and design blueprints for military equipment—including communications devices—from Germany, while Germany sought raw materials from Japan such as molybdenum, wolfram (tungsten), tin, and rubber, mainly obtained from Japan’s southern occupied territories.

However, at the time the Japan–Germany economic cooperation agreement was concluded, maritime traffic (Note 37) between Japan and Germany had already become virtually impossible. The British naval blockade, the severing of the Trans-Siberian Railway due to the German–Soviet War and—after the Battle of Midway—the intensifying U.S. offensive all contributed to the collapse of logistical routes. In practice, the only exchanges that continued between the two countries amounted to small quantities of materials and documents transported by submarine. The large-scale movement of machinery or personnel was entirely unfeasible. Precisely for this reason, Japan’s requests to Germany increasingly centered on “information resources,” such as technical designs and blueprints, whose value rose significantly under such circumstances.

Yet because this “information” largely concerned “military materiel”—that is, sensitive technologies—the pursuit of technical cooperation between Japan and Germany encountered multiple obstacles (Note 38).

(1) Defining “military equipment”

The first issue was the lack of a common definition of “military equipment.”

Although each country interpreted the term according to its own domestic legislation, no unified definition existed between Japan and Germany—this was long before international frameworks for arms export control like the Wassenaar Arrangement.

For example, Germany defined “military equipment” broadly to include not only weapons and warships but also training measurement devices, large motorcycles, aircraft engines, smoke-screen materials, military communications equipment, binoculars, and even field cooking gear. Japan’s Army and Navy, however, employed different classifications. The Army questioned whether “landing craft” or “radio-wave weapons” should be included, while the Navy argued that radio-wave weapons systems were part of “communications weapons” under its own definitions and insisted that excluding them from cooperation would be unacceptable.

Ultimately, while the Japanese Army and Navy stated that the definition was “generally” the same as Germany’s, no unified definition was adopted in practice. The final arrangement stipulated that the supplying country would determine, under its own laws, whether an item constituted military equipment.

(2) Clarifying the handling of “manufacturing rights” (i.e., patent licensing)

A second major issue was the handling of patent licenses.

In Germany, private companies frequently owned patents for military equipment, whereas in Japan such cases were rare. This raised concerns such as the following:

If Germany requested a license from a Japanese private company, could that company legally conclude such a contract under wartime secrecy laws and provide technology to Germany?

It became clear that Japan lacked a mechanism that resolved this scenario. The solution was for the Japanese government to “compensate” (effectively purchase) the patents from private companies, and then provide them to Germany. Government officials would also attend business negotiations to ensure smooth agreement on the handling of sensitive technologies.

In reality, as noted earlier, Japan mostly supplied raw materials rather than technology, but mutual technical cooperation remained one of the stated objectives.

(3) Issues concerning government-to-government payments

In the area of technical cooperation, Germany had already extended to Japan a credit line of 60 million Reichsmarks (equivalent to roughly 48 billion yen in today’s terms (Note 39). Yet Japan lacked both the mechanisms and the budgetary capacity to make payments that would be commensurate with this framework. For example, by late February 1944, the Army and Navy had estimated that royalty payments—already disbursed or expected to be disbursed—would total 100 million yen for the fiscal year beginning in April 1943 (equivalent to an estimated 100 billion to 200 billion yen today (Note 40). Under wartime conditions, Japan clearly had little financial room to maneuver.

It was in this context that the German government—particularly its leadership—conveyed a proposal to Japan: in order to facilitate Japan’s desire for the swift conclusion of licensing agreements, why not postpone the formal determination of royalty prices and all associated payments until after the war? The Japanese side, concerned that over-deliberation on prices might cause technical cooperation to stall as the war situation deteriorated, viewed the proposal favorably. As a result of subsequent consultations, both governments agreed that the total mutual obligations—specifically, the net balance after offsetting claims—would be clarified only after a “victorious end” to the war.

Having overcome these hurdles, in March 1944 Japan and Germany finally concluded the Agreement on the Mutual Provision of Manufacturing Rights and Raw Materials. Selected excerpts from the text are presented below.

Japan–Germany Arrangement on the Mutual Provision of Manufacturing Rights and Raw Materials (2 March 1944) (Note 41)

Pursuant to Articles 1 and 4 of the Agreement between Japan and Germany on Economic Cooperation, signed on 20 January 1943, the competent authorities of the Government of the Empire of Japan and the Government of Germany hereby agree as follows:

Article 1

The Government of the Empire of Japan and the Government of Germany shall mutually provide all manufacturing rights specific to military equipment intended for use during the continuation of the war, as well as all raw materials necessary for wartime economic management.

The interpretation of the concept of “military equipment” shall be based on the laws and regulations of the country providing the manufacturing rights.

The items considered most important by the German Government are molybdenum, wolfram (tungsten), tin, and rubber.

The German Government shall notify the Government of the Empire of Japan, as necessary, of the quantities of raw materials required for the prosecution of the war.

Article 2

Between the two governments, deliveries shall be made without calculating costs or making payments.

The Government of the Empire of Japan and the Government of Germany shall domestically process any claims made by holders of manufacturing rights as well as raw materials within Japan or Germany.

Article 3

Notwithstanding the principle set forth in Article 2, the customary conditions governing the transfer of manufacturing rights—particularly the subject, scope, duration, and confidentiality of the rights—shall be agreed directly between the competent authorities of Japan or Germany acquiring such manufacturing rights.

Article 4

The costs of the respective benefits shall be determined only after the two countries have achieved their joint victory in the war. At that time, the two governments shall reach mutual understanding on the adjustment of any differences that may arise.

For reference purposes only, each government shall unilaterally determine and notify the other of costs.

Article 5

The two governments mutually consent to allow the other party to use special industrial manufacturing methods and manufacturing rights that are important for the prosecution of the war but are not related to military materials.

In the commercial negotiations concerning the acquisition of such manufacturing methods and manufacturing rights, both governments shall provide mediation.

Article 6

In determining costs, the principle shall apply that no account is to be taken of special circumstances arising from the war.

Article 7

This Arrangement shall enter into force upon signature. This Arrangement shall remain confidential.

Executed in Berlin on 2 March 1944 (Shōwa 19), in two originals, each in the Japanese and German languages.

Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary of the Empire of Japan

Emil Wiehl

Director-General, Trade Bureau, German Foreign Office

According to archival sources from January 1945, the actual outcomes achieved under this Arrangement were as shown in Table 3. The Japanese side assessed that the contributions provided by Japan were “far smaller compared with those provided by the German side.” (Note 42)

Let us now return to the present and consider the scope for Japan–Germany policy cooperation in the field of economic security.

Building on points (1), (2), and (3) discussed earlier, would it be reasonable to draw the following conclusions—1, 2, and 3—as areas in which Japan could improve its own measures in order to advance economic security cooperation with Germany? And given that Japan–Germany economic cooperation during the war was severely constrained in terms of securing supply routes, is there also room to consider point 4?

1. Alignment of definitions for concrete items and technologies

With regard to specific items and technologies that are to be promoted through policy cooperation (for example, by designating them as eligible fields for subsidies or preferential tax treatment), has a minimum necessary alignment of definitions between Germany and Japan been achieved?

- ➤At present, there are international frameworks for arms export control such as the Wassenaar Arrangement, and in Japan, the Act on Strengthening Industrial Competitiveness and Economic Security refers to critical resources and advanced technologies. However, in this era of expanding dual-use technologies, whether specific items and technologies fall within the scope of policy promotion (i.e., whether they are subject to or exempt from regulation) can still become a point of contention. Endless debate would be futile; therefore, is it not necessary to at least confirm whether a minimum alignment of definitions exists?

2. Administrative support and schemes for licensing and technology transfer

On the assumption that German government entities or German companies and their Japanese counterparts would conclude licensing agreements and mutually provide technologies, are administrative procedural support measures, subsidy programs, and guidelines under the export control system for security trade adequately developed?

- ➤At present, there are overseas-related intellectual property support measures, such as subsidies for foreign patent application costs for Japanese companies, and support for international standardization. Furthermore, from the “Economic Security Key Technology Development Program” (hereinafter, the K Program), which was established under the leadership of the Cabinet Office to support cutting-edge technology development, to the “Monozukuri Subsidy” under the Small and Medium Enterprise Productivity Revolution Promotion Project—used by many SMEs for capital investment—costs related to intellectual property rights are also included as eligible expenses for subsidies. However, is support for licensing agreements with foreign governments or foreign companies truly sufficient?

- ➤Through the dispatch of export control advisors under SME outreach programs, or through mechanisms such as the K Program, is it possible to support the conclusion of licensing agreements with foreign governments or foreign companies? Should the appropriateness of covering such support under these measures themselves be examined from the outset?

3. Budgetary treatment of costs arising from cooperation with Germany

Is it possible to secure budgetary allocations for costs that arise in the context of economic cooperation with Germany?

- ➤As stated in point 2, there are currently intellectual property support measures related to overseas activities. There are also government-affiliated financial institutions involved in overseas expansion support, such as the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) and Nippon Export and Investment Insurance (NEXI), and numerous subsidy programs related to overseas expansion exist. At a glance, the “boxes” of budgetary measures appear to be sufficient, but are the internal schemes themselves adequate?

- ➤Is it possible to estimate the revenues and expenditures of the Japanese government and Japanese private enterprises arising from licensing agreements? Based on that, could a method be adopted whereby Japan’s revenues and expenditures are offset at year-end or under similar timings, and only the net excess of payments to the German side is disbursed?

- ➤Should appropriate funding measures take the form of general account budget allocations based on budget requests from each ministry, or financing and equity participation through government-affiliated financial institutions by utilizing Fiscal Investment and Loan Program funds?

- ➤Would it be reasonable to set EBPM (Evidence-Based Policy Making) indicators for budgetary measures, for example, as the annual sales of licensing-related products of Japanese private enterprises?

- ➤Are the scope of eligible beneficiaries and the upper limits of support comparable to, and not inferior to, German support measures?

4. Scope for diversifying the logistics of physical supply itself

Is there any realistic room for diversifying physical supply routes in the literal sense?

- ➤Even now, the geographical positions of Japan and Germany remain largely unchanged (indeed, their areas of effective control have shrunk compared with the period of World War II), and therefore long-distance logistics networks are a continued requirement.

- ➤Apart from the Suez Canal and the Strait of Malacca, what alternative routes exist for the movement of goods between Japan and Germany? While trade by submarine is no longer conceivable, is there room to further support the development of Arctic shipping routes or the expansion of air cargo capacity?

As an example, let us take a closer look at point 3 above.

In Germany, the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Energy conducts a subsidy program aimed at promoting WIPANO (Note 45)—the transfer of technology and knowledge through patents, standardization, and norm-setting, enabling the commercial utilization of innovative ideas originating from universities and firms. The program consists of the following components:

- Support for patent filing costs incurred by German firms

- ➤Up to EUR 6,000 for feasibility studies (approx. JPY 1.05 million) and EUR 10,000 for actual patent filings (approx. JPY 1.75 million), both with a subsidy rate of 50%.

- Support for patent-related standardization efforts by German firms

- ➤Up to EUR 45,000 (approx. JPY 7.9 million), with a subsidy rate of 70%.

- Support for standardizing the latest research outcomes through industry–academia collaboration

- ➤Up to EUR 200,000 per participating organization or per project (approx. JPY 35 million).

Subsidy rates: 50% for large firms, 80% for SMEs, and 85% for universities and research institutes.

- ➤Up to EUR 200,000 per participating organization or per project (approx. JPY 35 million).

For FY2025, a total budget of approximately EUR 20 million (Note 46) (approx. JPY 3.63 billion) has been allocated to this program.

In Japan, as mentioned earlier in point 2, there are numerous support measures under which costs incurred in relation to intellectual property rights are included within the scope of eligibility for subsidies. However, when examining the above German programs, is there not room for further consideration regarding the scale of funding and the subsidy rates by type of beneficiary? Along with a deeper examination of the issues raised in points 1, 2, and 4, I would like to position these as areas for future study.

Historically, technological cooperation has been one of the central pillars of Japan–Germany economic collaboration. In this sense, such cooperation can be understood as referring to policies surrounding patent rights themselves. From an implementation standpoint, concrete policy tasks range widely, from defining the technologies and items subject to patent cooperation, to considering the appropriate contractual frameworks, and securing the necessary financial resources. Even today, when economic security has become a major policy theme, it would be beneficial to continuously examine—and, where appropriate, recalibrate—the necessity and content of fundamental guidelines and fiscal measures, and to gradually shape them into concrete policies.

In Lieu of a Conclusion

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine shows no sign of ending. China has commissioned its third aircraft carrier, the Fujian. Even the United States—long regarded as the anchor of the democratic camp—now occasionally adopts a tougher stance toward its allies. Under such circumstances, the international security environment is undeniably growing more severe. To sustain economic growth, and to secure “economic security,” the domain where national security and economic policy intersect, governments must prepare policies that take every possible contingency into account.

Here once again, Dr. Wahlers responded to our concerns.

We must remember that consumers cannot be forced to buy specific products. In the automobile sector, for example, Ford certainly operates in the German market. But if German consumers were to consider purchasing a non-German car, they would likely choose a Toyota—because its safety and performance are superior.

Since ancient times, any policy has been meaningless if it failed to consider the consumer’s perspective on household goods, the dining table, and the scenery of everyday life. Even states that are labelled “authoritarian” cannot entirely disregard public sentiment; no country survives by ignoring its people. Policies designed to anticipate contingencies and the economies they aim to generate must, in the end, be accepted by society. To achieve that, what is needed is not the deployment of non-tariff barriers, nor an attempt to dominate markets with artificially cheap goods, but a distinctively Japanese approach grounded in non-price factors—quality, lifecycle cost, reliability, and concepts that genuinely resonate with consumers.

Germany and Japan can no longer be described as members of “a permanently secure Western Bloc.” It is precisely because this is no longer the case that the two countries must strengthen their cooperation now—as partners in a “Global West as pioneers” who share long-standing values and a history of policy collaboration, and who are prepared to carve out a new future together.

December 1, 2025

>> Original text in Japanese