Trade and trade policy have been in trouble in recent times. First, we have seen a decline in world trade growth, most notably since the global financial crisis. Second, larger shares of the electorate in several advanced economies vote for parties that have a negative view of trade agreements and international integration more broadly. This column briefly reviews what we know on the determinants of the global trade slowdown and on how trade agreements, both preferential and multilateral, have contributed to world trade. Trade cooperation has been a pillar of trade growth, promoting market access and supporting the development of global value chains (GVCs) in the last quarter century. A swing away from the policy of deep integration would hurt prospects for global trade growth going forward. But trade pessimism should not be overstated as the rationale for open trade and the demand for trade cooperation remain strong.

The trade slowdown

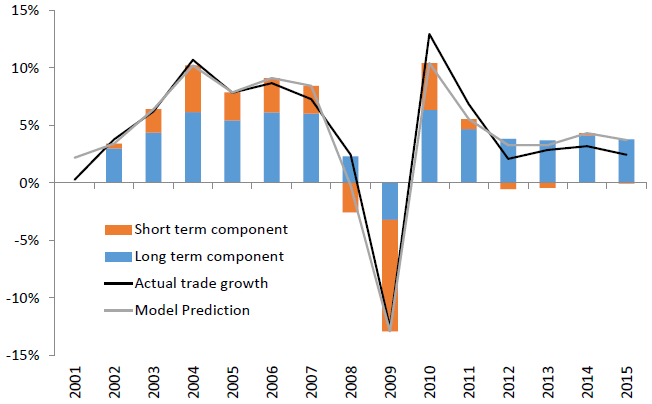

World trade grew at about 3 percent per annum in 2012-2015, which is much less than the pre-crisis average of 7 percent for 1987-2007 and less than the growth of gross domestic product (GDP). Preliminary data for the first three quarters of 2016 indicate that world trade growth could be even more anemic this year, at an annual rate of close to 1 percent. Previous work has shown that world trade is growing slowly not only because GDP growth is sluggish, but also because the long-run relationship between trade and GDP is changing (GEP, 2015; Constantinescu et al. 2015). The elasticity of world trade to GDP was larger than 2 in the 1990s but closer to 1 and declining throughout the 2000s. The change in the responsiveness of world trade to GDP was found to account for close to half of the global trade slowdown, with weakness of global demand and other cyclical factors explaining the remaining half (Figure 1).

Changes in the trade regime are a possible reason for the lower long run elasticity of world trade to income. In the 1990s and early 2000s, reforms in anticipation of and resulting from WTO membership allowed countries, most notably China, to rapidly integrate into the global trading system. Applied tariffs fell from averages of nearly 30 percent to less than 15 percent in emerging and developing countries and from 10 percent to less than 5 percent in industrial countries. Similarly, the number of preferential trade agreements (PTAs) surged from 50 in the early 1990s to around 200 in the early 2000s to reach 279 in 2015. Increasingly, agreements covered a growing number of policy areas, from investment to competition policy and intellectual property rights (Hofmann et al. 2016). Some of these agreements, such as the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994 and the enlargement of the EU in the early 2000s, had a truly transformative effect on the economies involved.

A related explanation for the changing long-run trade elasticity is the varying pace of international vertical specialization. In the 1990s, the information and communications technology shock and the deepening of trade agreements led to a rapid expansion of global value chains. The resulting increases in back-and-forth trade in components led to measured trade racing ahead of national income. The decline in the long-term responsiveness of trade with respect to income in the 2000s may well be a symptom that the technology and policy shocks of the 1990s have been absorbed and that the process of international production fragmentation has slowed down.

To illustrate the importance of GVCs and trade reforms in the current trade slowdown, I report regression results from Constantinescu et al. (2015). In that study, we regress the implied elasticity of global merchandise trade to income (calculated as growth of trade in goods divided by GDP growth) on a set of explanatory variables that have been suggested in the academic literature as leading drivers of the decline in long-run trade elasticity (Hoekman, 2015). The focus is on four sets of variables: i) changes in vertical specialization to capture variation in GVC participation; ii) changes in tariffs to capture the fundamental openness of the trade regime; iii) changes in contingent protection, such as anti-dumping measures, to capture variation in temporary protection; and iv) changes in the investment share in GDP to capture variation in the composition of demand.

The analysis allows us to assess the contribution of each explanatory variable to the change in trade elasticity to income over time (Note 1). The average trade elasticity was 1.8 during 2001-2014 (excl. 2009) compared to 2.6 during 1991-2000. The largest contributions to the decline come from vertical specialization. Specifically, the changes in the average growth of vertical specialization (from 3.1 percent in the first period to -1.0 percent in the second period) account for a decline in trade elasticity of 0.4. The slowing pace of tariff liberalization also matters. The decline in the average growth in tariff (from 6.6 percent in the first period to 2.3 percent in the second period) accounts for a similar share of the fall in trade elasticity. Other factors matter less.

The role of trade agreements in promoting trade

I next look at the same question from a different angle. How much did trade agreements contribute to the growth of world trade in recent decades? To address this question I rely on joint research with Aaditya Mattoo and Alen Mulabdic at the World Bank (Mattoo et al. 2016). First, we investigate the extent to which trade agreements contributed to boost trade among members. We use trade data from the World Input Output Database (WIOD) and the World Bank data on the content of preferential agreements to estimate a gravity equation augmented with a measure of depth for the period 1995-2014. By including dummies identifying the year of WTO entry of a country, we can also quantify separately the effect of trade agreements from the one of WTO membership. We find that the deepest PTAs have more than doubled trade among members in the long term. WTO membership increases trade by 65 percent in the long term.

We then use these estimates to build counterfactual scenarios. Specifically, we assume that in the period 1995-2014 no trade agreement was signed and no new member joined the WTO and ask what the impact on world trade would have been. We find that trade agreements (both preferential and multilateral) account for around 40 percent of world trade growth for the period (Table 1). We can further break down this number to account separately for the impact of WTO membership and preferential trade agreements. The compound annual growth rate of world trade for this period was 6.5 percent. If in this period no new member had acceded the WTO (e.g. if China had not entered the WTO in 2001 as it did), world trade would have grown 1 percentage point less between 1995 and 2014. If no new PTA were signed (e.g. if Eastern and Central European countries had not acceded the EU in 2004), world trade would have grown by a further 0.8 percentage points less per year. In other words, the combined effect of no preferential trade agreements and no new WTO members would have been to reduce the annual growth rate of world trade from the actual 6.5 percent to 4.7 percent.

| Observed | No change in trade policy (Preferential and Multilateral) |

No change in PTAs | No new WTO members | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Growth rate of world trade(1995-2014) | 232 | 142 | 200 | 175 |

| Growth rate of world trade(annual) | 6.53 | 4.76 | 5.95 | 5.46 |

| Note: Counterfactuals are based on a gravity model estimated by PPML which includes country-pair, exporter-year, and importer-year fixed effects in addition to a depth variable and WTO dummy for both of which we include lagged variables up to 10 years to capture dynamic effects. | ||||

A bleak trade future?

Trade growth has been slow in recent years and appears to have plateaued in 2016. There are both cyclical and structural factors behind these developments, including the weaker growth of the world economy since the financial crisis, the slower expansion of global value chains and the reduced pace of trade liberalization in recent years. Trade agreements, in particular, have largely contributed to the expansion of world trade in the past. A stalemate or even a reversal of the deepening of international trade cooperation would certainly have a significant negative impact on trade growth going forward. While difficult to quantify, the uncertainty on the future course of trade policy in leading advanced economies may be already contributing to weaker world trade growth today.

But pessimism on the prospects for trade should not be overstated. First, the scope for trade integration is still strong. Reforms aimed at reducing trade costs could lead to efficiency gains by improving access to markets and expanding global value chains, particularly to regions and countries that have missed out on these opportunities in the past. Second, while the future of important agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership is in question, other initiatives like the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership may gain momentum as the demand for integration in most developing and emerging economies remains strong. Finally, and more fundamentally, the deepening of trade agreements and multilateral economic cooperation more broadly is a long term phenomenon that responds to the needs of an evolving global economy. The deterioration in public attitudes towards integration in certain advanced economies is not inevitable and could be addressed if governments put in place the complementary policies that allow the benefits from openness to be shared more widely.

* This column is based on joint work with Cristina Constantinescu, Aaditya Mattoo and Alen Mulabdic at the World Bank. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and they do not necessarily represent the views of the World Bank Group.