| Author Name | ARMSTRONG, Shiro (Non-Resident Fellow, RIETI) / Jacob TAYLOR (The Brookings Institution) |

|---|---|

| Download / Links |

This Non Technical Summary does not constitute part of the above-captioned Discussion Paper but has been prepared for the purpose of providing a bold outline of the paper, based on findings from the analysis for the paper and focusing primarily on their implications for policy. For details of the analysis, read the captioned Discussion Paper. Views expressed in this Non Technical Summary are solely those of the individual author(s), and do not necessarily represent the views of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI).

The world has crossed a threshold where the digital economy is now the key driver of value in the global economy. The digital economy makes up more than 15% of global GDP and has grown two and a half times faster than world physical GDP over the last 10 years. The World Economic Forum estimates that 70% of new value created over the coming decade will be based on digitally-enabled platform business models. Much of trade in physical goods and services is now dependent on data-driven insights produced from these physical flows.

Systems of data, software, computation, and talent promises significant productivity growth and new opportunities for improving welfare. But it also presents new challenges to societies and policymakers globally. The digital divide between rich and poor countries and vulnerable populations within all countries is extreme. In 2023, one-third of the world’s population, or 2.6 billion people remained offline, a disproportionate number of whom were women, indigenous people, and rural residents. Meanwhile, 2023 heralded a new wave of innovation in generative AI models now set to turbocharge the digital economy by serving as ‘foundation models’ for a new industrial layer.

Frontier digital and AI systems present new opportunities for societies to address challenges that were previously too costly or not possible, such as increasing worker productivity in sectors like healthcare and education, identifying tailored solutions in disability or social welfare support across heterogeneous societies, or global-scale biodiversity monitoring or pandemic preparedness systems.

At the same time, the speed and scale of growth in the digital economy and generative AI are exacerbating existing risks around personal privacy, cyber security, and IP protection, while also creating entirely new risks. Some are easily recognizable in the form of deepfakes and misinformation, while others are harder to identify, such as single point of failure vulnerabilities in computational infrastructure, algorithmic biases and discrimination, or the environmental impacts of massive-scale computational systems. Slowing the use of frontier digital and AI technologies in one jurisdiction — if it were even possible — would not mitigate risks from other jurisdictions in a digital world where borders matter less.

Globally-inclusive, multilateral arrangements for digital and AI governance can help address many of these risks by helping align incentives and establish shared norms between all actors. But developing multilateral digital and AI governance is not easy in the current disruptive global environment. A range of interconnected, transnational challenges—including climate change, the collapse of biodiversity, conflict, inequality and indebtedness—are outpacing international institutions designed to manage such challenges.

Despite considerable progress on digital economy and e-commerce rulemaking within plurilateral settings such as the World Trade Organization’s Joint Statement Initiative and evolution of the Japan-led concept of Data Free Flow with Trust (DFFT) within G20 and G7 groupings, the global digital economy remains highly fragmented. It is at risk of coalescing around three blocs—the United States and its allies, China and the European Union. Balkanization of digital governance, including key gaps in membership and rules, threatens to further fuel geopolitical rivalry and adversely affect economic dynamism and interdependence in goods and services trade.

In this context, continued engagement in existing multilateral rule making and consensus building processes remains important but engagement alone is not sufficient. New approaches to multilateral governance are needed that can more evenly distribute the benefits of digital and AI systems while collectively managing their risks.

This paper provides three building blocks for new approaches to multilateral governance of the digital economy and AI.

First, this paper analyses the economic logic of value creation in the digital economy and the policy dilemmas that this logic implies. Since key components of digital economic activity have public good features, with data and software being able to be used by many simultaneously, barriers to free flow of data, software, and talent are particularly detrimental for economic growth and development within and between countries. Monopolistic hoarding of these components by technology firms and barriers to digital trade across borders and jurisdictions affect supply chains, productivity, peoples’ livelihoods, and reduce the growth potential of economies, including those at the global technological frontier. There is a need for policy solutions that liberalize flows of data and software while incentivizing business innovation and protecting against risks.

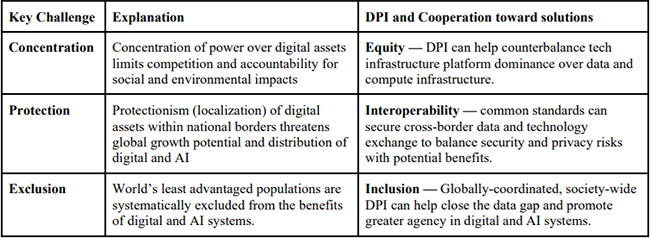

Second, this paper identifies major economic and political challenges that impede efforts to advance multilateral governance, including concentration of power, protectionism, and exclusion in digital and AI systems. A key challenge for policymakers will be finding more globally-inclusive ways to harness the economic and societal value of digital and AI systems while preserving important foundations of the digital economy, including individual privacy, cybersecurity, and civil society oversight.

Third, this paper evaluates the potential of Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI)—an increasingly globally-recognized framework for developing inclusive, interoperable, and publicly guaranteed digital ecosystems—to help advance global digital and AI governance. By creating a ‘level playing field’ for inclusive and competitive digital economic activity within (and potentially between) countries, global proliferation of DPI (especially digital ID, payments, and data exchanges) could help establish a stronger foundation for multilateral digital and AI governance in the years to come.

[Click to enlarge]

Developing shared guiding principles can help enhance the opportunities and positive spillovers from the new technologies while managing risks and negative spillovers across borders. Establishing links between DPI and AI within multilateral settings like ASEAN, APEC and regional trade agreements like RCEP can help encourage dialogue between major powers like China, India, Indonesia, and the US with the help of influential middle powers like Australia, Japan, and Singapore. Sound domestic regulation guided by experience sharing and share interests, aligned and connected through multilateral principles can create a framework to manage the key challenges in the global political economy of digital and AI governance.