In the world of Japanese politics in the 21st century, as a result of the political and administrative reforms since the 1990s, a system of government driven by political leadership—which may also be called a system led by the Prime Minister’s Office—has taken hold. The Koizumi administration introduced a system whereby the Prime Minister’s Office exercised leadership in making policy decisions in the early 2000s, and later, the government of the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) (which briefly replaced the long-dominant Liberal Democratic Party (LPD) as the governing party) upheld the slogan of “destroying the bureaucracy-led system of government.” The trend of transferring policy making power from the civil service to the Prime Minister’s Office became even more pronounced under the second Abe administration. The establishment of the Cabinet Bureau of Personnel Affairs in 2014 is considered to have given the Prime Minister’s Office a decisive influence over the civil service.

Many of the political reform initiatives carried out in Japan in order to strengthen the leadership of politicians and the Prime Minister have been modelled on British politics. The argument for introducing the single-member district system as part of the political reform in Japan was in large part underpinned by a desire to realize a British-style political system that is conducive to a change of government between major political parties. The various politician-led initiatives launched under the DPJ government were also modelled on the leadership style of the British administration under Tony Blair, which relied on his inner circle’s initiatives.

This column looks at the relationship between politicians and civil servants and the civil service reform in the United Kingdom and considers the insights that may be gained for the future of political leadership and the civil service system in Japan.

◆◆◆

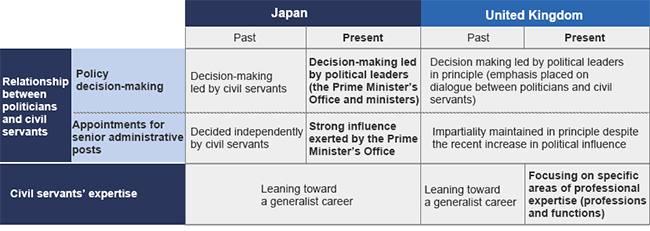

When we think about the relationship between politicians and civil servants in the United Kingdom, it is important to look at the relationship from two separate viewpoints—policy decision-making and appointments of civil servants for senior administrative posts. Regarding policy decision-making, it is ensured that ministers lead the civil service. However, that does not mean that ministers merely unilaterally provide orders to civil servants. When developing policy details, civil servants raise necessary points in relation to policy outlines presented by ministers. In other words, policy making is a process of dialogue between ministers and civil servants; however, ultimately, policies are finalized based on ministers’ decisions.

On the other hand, ministers’ authority over appointments of civil servants to senior administrative posts is limited. In the case of the appointments of permanent secretaries, before 2014, a panel under the Civil Service Commission, which is an independent organisation, selected and recommended to the prime minister one candidate for each post. If the prime minister rejected a recommended candidate, the selection process would have to start over, so the prime minister typically provided his approval as a matter of course in most cases.

However, because of the ministers’ weak authority over appointments relative to their influence in policy decision-making, discontent grew within the ruling party. Therefore, under the Cameron administration, the system was reformed. As a result, since December 2014, regarding appointments for permanent secretaries, the Prime Minister nominates one of several candidates recommended by the panel under the Civil Service Commission.

Even after this reform, the politicians’ authority over appointments for senior administrative posts has remained relatively weak. Although some people point out that in the actual candidate selection process the intentions of the prime minister as well as ministers are taken into account, it does not mean that the politicians have discretion in appointing top administrative officials. British political leaders’ authority over appointments has been far more limited than the power wielded by the Prime Minister’s Office in Japan since the establishment of the Cabinet Bureau of Personnel Affairs.

Although the politicians’ influence over appointments has been increased to some degree in the United Kingdom, impartiality of the civil service has been maintained in principle. Moreover, on the part of politicians as well, there is full awareness about the importance of the impartiality of the civil service.

The impartiality of the civil service affects the effectiveness of Evidence-Based Policy Making (EBPM). The EBPM approach has taken hold under successive British governments following the Blair administration. To implement the EBPM approach, it is essential to take advantage of civil servants’ expertise, and to do that, it is necessary to develop a system to enable civil servants to advise ministers on policy options from an impartial standpoint.

[Click to enlarge]

However, the relationship between politicians and civil servants in the United Kingdom is not perfect. In fact, many problems have emerged. In April 2023, Deputy Prime Minister Dominic Raab, who was concurrently serving as Secretary of State for Justice, resigned over the alleged bullying of civil servants. The incident came against the backdrop of growing distrust between ministers and civil servants. According to reports by the British newspaper The Times, while ministers have doubts about civil servants’ competence, the bureaucrats believe that the ministers’ policy initiatives are hastily prepared and flawed.

Following the political turmoil in the United Kingdom after the exit from the European Union (Brexit), Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, speaking in an inaugural address, pledged that the government would “have integrity, professionalism, and accountability at every level.” His administration faces a test on whether it can deliver on that pledge in terms of the relationship between politicians and civil servants.

◆◆◆

Another point of interest regarding the British civil service is the reform implemented to raise the level of expertise of civil servants.

Basically, bureaucracy has a vertical organisational structure, but what stands out about the reform of the British civil service is the introduction of horizontal networks that cut across government departments. Under the Blair administration, “professions,” or cross-governmental networks including policy making, were introduced, and under the Cameron administration, cross-governmental “functions,” that are grouped across government to enhance functional work such as finance, human resources (HR) and communication, were introduced. Civil servants may belong to those cross-governmental networks while being affiliated with individual ministries and agencies.

Currently, there are 28 professions and 14 functions. This system helps civil servants improve their expertise and build a career, and it supports efficient implementation of each ministry’s work by defining expertise, by specifying job objectives, required competencies and standards, by presenting career paths, and by providing various training opportunities.

Over the past 10 years, the British government has devoted particular efforts to three functions—commercial (e.g., procurement and contract management); project delivery; and digital, data and technology. This reflects the government’s policy of promoting cost savings and improving efficiency under fiscal austerity.

To date, it has been observed that the functions have improved the level of expertise within departments, which has resulted in increased operational efficiency and cost savings, and that the functions have played an infrastructural role in cross-departmental responses in emergencies.

British civil servants are not subject to regular job transfers determined by the HR section . Job transfers are implemented based on individuals’ applications for publicly offered vacant posts, and this means that civil servants must make proactive efforts to build their own careers. The introduction of standards for tasks and skills and a certification system for professional competence, which are common to all ministries, has facilitated inter-departmental transfers and enabled wider and more flexible career development. The horizontal networks have contributed not only to the improvement of civil servants’ competence but also to the enhancement of motivation and autonomy.

It is not easy to introduce a horizontal network into the current vertical structure of the bureaucracy that constitutes government organisations. Trial and error continue in the United Kingdom, and the system is being built through a series of modifications. An organisational culture that is receptive to change and diversity is also key for the two to work together effectively.

To realise better policy making, it is important that civil servants can advise ministers on policies from an impartial standpoint and based on professional knowledge while maintaining some degree of autonomy. In the United Kingdom, the Civil Service Commission and cross-departmental networks have underpinned the impartiality and expertise of civil servants.

It is hoped that Japan's civil service reform will also incorporate these perspectives. For example, a screening system by an independent panel for appointments for senior administrative posts and a government-wide network for each governmental function to foster expertise could be considered.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

October 3, 2023 Nihon Keizai Shimbun