Recent economic news articles have frequently included the word “independence.” In particular, President Donald Trump fired a Federal Reserve Governor and exerted overt pressure on Fed Chairman Jerome Powell to ease monetary policy, jeopardizing the independence of the U.S. central bank.

In Japan, under the condition of a minority ruling party, pressure for fiscal expansion has been relentless. As a countermeasure to limit the pressure, economists and groups like “Reiwa Rincho” have proposed the creation of an independent fiscal institution to monitor, analyze, and advise on fiscal policy and relevant achievements on a non-partisan basis.

Since political motivations provide the government with a bias toward expansionary monetary and fiscal policies, the independence of such an institution is necessary to prevent government intervention and to impose discipline.

Even in the private sector, there are institutions where independence has been emphasized. They are known as corporate boards of directors. Directors are not subordinates of the CEO; they represent shareholder interests, oversee business, and have the authority to dismiss the CEO if necessary.

Therefore, in order to fulfill those responsibilities, it is important that a certain number of independent external individuals are selected as directors, instead of simply selecting people with close ties to the company or promoting internal executives, who tend to be more prone to colluding with the CEO. The introduction of independent outside directors has been a central theme in Japan's corporate governance reform, which has been promoted for more than a decade.

It is well established in economics that central banks, independent fiscal institutions, and boards of directors should have sufficient independence, and I have no intention of disputing that principle. This is because the performance of the duties necessary to achieve the inherent goals of the institutions is susceptible to interference from third parties, as noted above. However, I suspect that independence has been overemphasized, as a dogmatic reflex.

◆◆◆

An example of such overemphasis is the pervasive idea that simply introducing systems or mechanisms to enhance independence will improve corporate or institutional performance. I believe that formal systems or mechanisms that are intended to enhance independence inherently have limitations and loopholes that can be exploited.

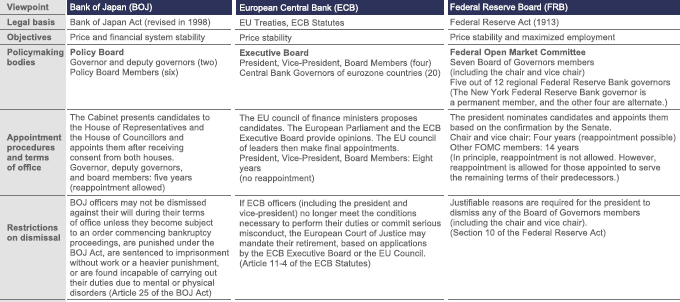

First, consider the case of the central bank. In order to ensure the central bank’s independence, measures have been taken such as establishing clear goals and placing restrictions on funding to be provided to the government. Additionally, procedures for appointing, setting terms of office, and dismissal mechanisms for bank governors and board members have been established to make external interference more difficult. For instance, in both Japan and the United States, central bank governors are not simply nominated by the government: they must be approved by the legislature (see the table).

[Click to enlarge]

To prevent the government from easily dismissing the governor and other officials, strict requirements are set for their dismissal. In principle, the government is barred from reappointing the governor or other policymakers and their terms are set to outlast the political cycle. These are recognized as methods to help prevent government intervention and increase the central bank’s independence.

Even if the government nominates the governor and other policymakers, their approval in the legislature is seen as a method of ensuring independence by having the central bank leaders approved by the legislature that reflects the will of the people instead of arbitrarily.

However, if the ruling party holds the majority in both legislative chambers, the government’s nominations are typically approved. If the government holds a biased policy ideology in such situation, it can appoint pro-government people who adhere to the same ideology, which could undermine the central bank’s independence.

What is even more problematic is that once such a person is appointed as governor, the long term of office and difficulty in dismissal can exacerbate the problem. It is difficult to clearly specify qualifications, competencies, and other requirements for the governor in advance. In many cases, the central bank’s independence depends on who is nominated. It would not be an exaggeration to say that the governor is nominated discretionally by the prime minister or the president who heads the executive branch.

The same argument applies to independent fiscal institutions such as the U.S. Congressional Budget Office (CBO) established in 1974 and the British Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) launched in 2010. The “Principles of Independent Fiscal Institutions” compiled by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in 2014 cite requirements for independence, such as a clear mandate and legal basis, staffing and funding independence from the government, direct accountability to the legislature, and recruitment and business operations based on transparent and professional analysis.

Independence related to personnel requires that the heads of independent fiscal institutions, like those for the central bank governor, hold long terms of office and protections against dismissal to prevent undue political influence. Regarding appointment procedures, strong legislative involvement is emphasized.

The director of the CBO is jointly appointed by the speaker of the House of Representatives and the President pro tempore of the Senate (the Vice President serves as Senate President) based on recommendations by the Budget Committees of both chambers. The President cannot be involved in the appointment. In the case of the OBR, the chair is appointed by the Chancellor of the Exchequer through a process that includes the nomination of a candidate by Her Majesty’s Treasury, and examination and recommendations by the Treasury Committees of the two chambers. In the case of the CBO, its budget is included in the congressional budget and Congress alone is authorized to dismiss the CBO director. The CBO is thus recognized as one of the most independent fiscal institutions in the world.

However, fiscal institutions have the same problems as central banks. Even if they are independent from the government in terms of structure, a ruling party with a majority in the legislature can appoint a director who supports the government’s fiscal policy as the head of the institution. Even the highly regarded CBO did not seem to apply fiscal discipline to the government in the 1980s, when budget deficits were a particularly controversial issue in the United States.

South Korea's National Assembly Budget Office (NABO) established in 2003 is also a legislative institution. The NABO chief is appointed by the National Assembly speaker with the consent of the House Steering Committee and the office, including its budget, is completely independent from the government. Furthermore, detailed procedures have been established for selecting the NABO chief candidate. A recommendation committee that consists of politically neutral experts produces lists and narrows down candidates for the chief before recommending a candidate to the National Assembly speaker. Such procedures will be useful when an independent fiscal institution is created in Japan.

◆◆◆

Ultimately, the independence of the independent institutions cited above depends on the qualities of their appointed heads. Whether the right people are selected as their heads depends on the qualities of government or company leaders making those nominations.

This means that no matter how many formal systems or mechanisms that are interpreted as conducive to the independence of these institutions are put in place, they do not constitute sufficient conditions for actual independence. We should bear in mind the folly of allowing form to exist without substance—of creating a “Buddha without a soul.” This is an issue that should be reconsidered alongside the limitations inherent to democracy in politics.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

September 15, 2025 Nihon Keizai Shimbun