Postwar Japan experienced sharp fluctuations in its currency exchange rate due to U.S.-led policy shifts, including the 1971 Nixon Shock. While Japan and Germany advanced with industrialization and overcame similar challenges since their defeat in World War II, significant differences have appeared between Japan’s and Germany’s current account structures over the past 40 years since the Plaza Accord in 1985. What factors contributed to these changes? I want to compare the paths taken by both countries and consider the future direction and actions Japan should pursue.

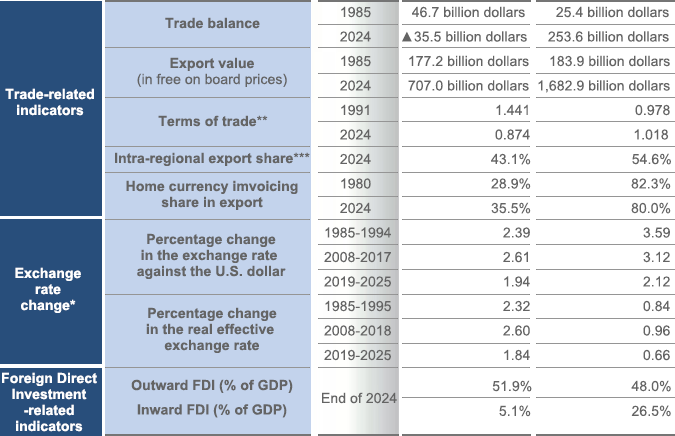

The upper part of the table compares trade data between Japan and Germany. While Japan had a larger trade surplus than Germany in 1985, by 2024, it recorded a trade deficit, whereas Germany maintained its trade surplus. The main reason for this difference is clearly shown in the export data. While Japan’s exports quadrupled during this period, Germany’s exports grew more than ninefold.

During this period, Japanese companies increased their overseas production share and maintained a current account surplus through the primary income balance, transitioning to “a mature creditor country” as outlined in the stages of balance of payments development found in the literature. However, as a result, Japan was surpassed by Germany in nominal GDP in 2023, once again highlighting Japan’s industrial hollowing-out.

◆◆◆

One factor contributing to their divergence is the difference in their currency environments. In the 1980s, the European foreign exchange market established a coordinated exchange rate system centered on the Deutsche Mark, which allowed other European currencies to remain stable against the Mark rather than the U.S. dollar.

In contrast, Japan, which has the only hard (international) currency in Asia, has experienced repeated sharp fluctuations in its exchange rate not only against other currencies of developed countries but also against currencies of other Asian nations, such as China.

Furthermore, Germany overcame the 1992-93 European currency crisis and achieved euro integration in 1999. On the other hand, although Japan experienced increasing momentum for the internationalization of the yen in the 1990s and proposed a dollar-euro-yen currency basket system to stabilize Asian currencies after the 1997-98 Asian currency crisis, nothing was accomplished.

This difference significantly influenced the trends of the yen and euro during and after the 2008 global financial crisis. The yen experienced a historic appreciation until Abenomics was introduced in late 2012. In contrast, Germany did not face any periods of major currency appreciation even during the subsequent European financial crisis.

The middle section of the table compares exchange rate volatility of the yen and the Deutsche Mark (euros after 1999) during periods following the Plaza Accord, the global financial crisis, and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Although the Mark/euro showed more volatility against the dollar than the yen in all periods, Germany's real effective exchange rate volatility was only about a third of Japan's.

To cope with price competition resulting from exchange rate changes, Japanese companies moved production to lower-cost Asian countries to maintain market share and avoid major export price increases. In contrast, German companies were able to differentiate their goods domestically under a stable, effective exchange rate and steadily increase export prices.

As a result, Germany has managed to maintain its terms of trade. Japan, unable to sufficiently increase export prices, experienced worsening terms of trade due to high resource prices, which make up most of its imports.

Furthermore, the proportion of exports denominated in domestic currency for Germany has consistently stayed around 80%, which is more than double Japan's, which is less than 40%. Finally, while Germany has a higher intra-regional export ratio and conducts most eurozone trade in euros, Japanese companies tend to trade in U.S. dollars more often than in yen, even for intra-Asia exports.

One reason the yen is not widely used in Asia is the rational choice by Japanese companies to denominate intra-company trade within their supply chains in dollars. In contrast, for other Asian companies, the main reason is the high volatility of the yen against the dollar. Japan, which has a large portion of its exports denominated in dollars, has long maintained the belief that a weak yen benefits the Japanese economy. However, now that Japan has entered a trade deficit, the disadvantages of a weak yen for the Japanese economy can no longer be overlooked.

Additionally, there are differences in direct investment trends. As shown in the bottom part of the table, Japan and Germany both have high foreign direct investment as a percentage of GDP (around 50%). Inward direct investment shows a different picture, with inward direct investment as a percentage of GDP at the end of 2024 exceeding 5% for Japan, compared to 26.5% for Germany.

Through euro integration, Germany has secured a stable currency exchange rate that is undervalued relative to its economic strength. Additionally, it has encouraged inward foreign direct investment by leveraging the European Union (EU), which expanded to include 27 countries in 2007. In Europe, where intra-regional trade is thriving, the ability of companies with operations in Germany to use the euro for tariff-free trade within the EU is enough to attract investment in Germany despite its high wages and prices.

In contrast, Japan’s historically strong yen after the global financial crisis further boosted outward direct investment, worsening the imbalance between foreign and inward direct investment. Since 2022, promoting inward direct investment has become a key goal for Japan’s economic recovery and a way to counteract yen depreciation, but invisible barriers have slowed progress.

◆◆◆

Richard Ku’s 1994 book “Yoi Endaka, Warui Endaka (Is a Strong Yen Good or Bad?)” pointed out the flaw in Japan’s way of thinking about how to operate within the current framework, while the United States addresses the framework itself. When I experienced the Plaza Accord and the European currency crisis in the London market while working at a bank, I thought it would be impossible for Germany to give up the Mark as the strongest currency and achieve European monetary integration.

However, Europe quickly established the eurozone and overcame the Greek crisis. The euro has now reached a historic high against the yen. The Japanese currency, once considered a safe-haven asset, has become much cheaper than the Swiss franc, which continues to hit record highs.

Since the era of the Plaza Accord, when the G5 countries gained control of exchange rate trends, international financial markets, including emerging countries, have become bloated and chaotic. Due to recently rising geopolitical risks, countries in the Global South led by China are encouraging transactions in their own currencies. Some studies indicate that the use of the Chinese yuan is expanding in Asia and among some emerging market countries.

It is undeniable that the introduction of reciprocal tariffs by U.S. President Donald Trump starting in 2025 will encourage U.S. trading partners to accelerate their efforts to reduce reliance on the dollar, altering its role as the dominant global currency.

There are concerns that the Trump administration might pursue a policy of devaluing the dollar to lower the U.S. trade deficit in the future, which could again lead to significant yen appreciation for Japan. Germany’s experiences since the Plaza Accord indicate that, for Japan, as a small, open economy, maintaining exchange rate stability is a vital policy challenge. Japan should fundamentally revise its current exchange rate and monetary policies and initiate comprehensive regional financial cooperation to establish an Asian bloc.

Asia's intra-regional trade makes up about 50%, which is still much lower than the 70% of the euro area. While Asia’s intra-regional trade share is around 50%, it remains well below the 70% for the euro zone. However, removing exchange rate risks in intra-regional trade could be a major advantage for Asia overall. Now might be a good time for Japan to step up efforts to make the yen a true international currency or even the main currency of Asia.

>> Original text in Japanese

* Translated by RIETI.

September 11, 2025 Nihon Keizai Shimbun