Corporate shareholders, such as banks and business corporations, used to dominate the top ranks in the list of shareholders of Japanese listed companies. The ownership structure of these companies was very stable and served as a basis for their business management based on a long-term perspective. This, however, has changed drastically over the past 15 years. The unwinding of cross-shareholding and an increase in the proportion of shares held by institutional investors, particularly those overseas, have been the main drivers of the changes.

While some critics blame that the increased presence of foreign shareholders is likely to make Japanese corporate managers focus on shortsighted goals, there remains a persistent view that no substantial change has been made to Japanese corporate governance, which is often described as being employee-oriented. In this column, I would like to examine the current state of Japanese corporate governance and explore future tasks.

♦ ♦ ♦

In analyzing the ownership structure, it is often useful to distinguish between two types of shareholders, namely, those holding shares in maximizing investment returns (outsiders) and those holding shares for purposes other than investment and/or capital gains (insiders). Insiders include company managers, employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) associations, banks, and corporations that are business partners of investee companies, whereas outsiders consist of Japanese and overseas institutional investors and individual shareholders. Up until recently, the proportion of shares held by institutional investors was insignificant.

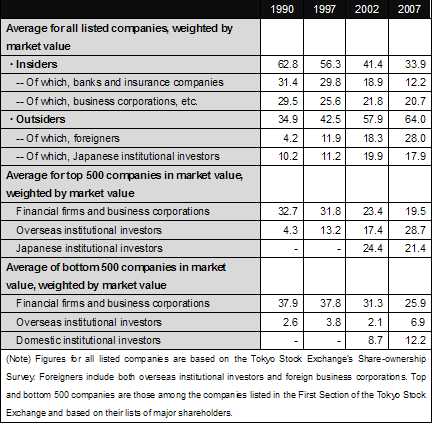

Ownership structure began to change in the 1990s. With the unfolding of financial globalization, the presence of overseas institutional investors increased significantly (see Figure). This trend was particularly conspicuous in large blue chip companies with well-established reputations in the market, high market capitalization, and high liquidity in their shares. At that point of time, however, the insider-dominated ownership structure had not collapsed.

Significant changes in the ownership structure of Japanese companies occurred after the banking crisis in 1997. Facing serious non-performing loan problems, banks sold their shareholdings, particularly in easy-to-sell blue-chip stocks, to secure funds to write off loan losses. On the other side of the cross-shareholding relationship, companies—led by those no longer dependent on banks for financing—began to sell their shareholdings in banks, considering its greater risk and shrinking returns. The sell-off of bank shares continued until 2005.

Meanwhile, overseas institutional investors' ownership of Japanese stocks further increased from 2003 onward. At the end of March 2007, when their ownership ratio peaked, overseas institutional investors owned 28% of the aggregate market value of all listed companies, while the ownership ratio for outsiders as a whole exceeded 60%.

From 2006, the business media began to pay attention to a resurgence of cross-shareholding against the backdrop of a series of hostile takeover attempts. However, no clear increase in the cross-shareholding ratio can be observed by aggregate data. Even when looking at firm-level data, we can find an increase in the cross-shareholding ratio only in those companies that are small in size, have boards of directors mainly composed of internally-promoted directors, retain a large amount of surplus funds, and have the experience of facing a takeover threat (large share purchases).

♦ ♦ ♦

What impact does the shift to the outsider-dominated structure have on the behavior of Japanese companies? First, findings from a recent empirical analysis in which I was involved show that the higher the institutional ownership ratio, the more forthcoming the companies were in enhancing information disclosure and implementing a range of governance reform measures—such as reducing the number of board members, introducing a corporate officers system, and appointing independent directors—since the late 1990s.

However, our interviews with leading foreign institutional investors showed that they have little preference on the form or structure of governance in selecting companies in which to invest, such that they have not considered the existence of independent directors, the introduction of a stock options program, and the availability of takeover defense measures—all of which are usually considered as important factors in exercising voting rights—as explicit factors. These factors are taken into consideration only when they are likely to contribute to (or impose constraints on) the formulation of a proper strategy for higher investment returns.

Second, the increased presence of institutional investors has had a substantial influence on corporate behavior. Recent empirical studies suggest that the high shareholding by foreign investors lead to faster employment adjustments in response to changes in sales, as well as more merger and acquisition (M&A) transactions as a growth strategy.

It has been pointed out that institutional investors have affected the dividend policy among Japanese companies and thus are responsible for their excessive dividend payments. In reality, however, Japanese companies' dividend payout ratios have increased only slightly since 2000 because their retained earnings increased largely in tandem with an increase in the amount paid out as dividends. Rather, more notable is the tendency for higher institutional ownership to increase the elasticity of dividends to earnings.

Moreover, an increase in the presence of institutional investors does not necessarily force companies to pursue short-sighted management. People often criticize that an increase in the presence of foreign investors could drive companies to reduce research and development (R&D) expenditures in order to achieve target profit levels or maintain dividend levels. However, my empirical analysis with Yasuhiro Arikawa and Takuya Kawanishi of Waseda University has found no evidence indicating that R&D expenditures were significantly affected by changes in current cash flows in companies with high institutional ownership. Rather, our interviews with leading foreign institutional investors found that a decrease in R&D and advertisement expenditures is taken as bad news.

Then, how is a company's performance affected by an increase in ownership by foreign institutional investors? In fact, it is not easy to identify the causal relationship between them. Institutional investors, by nature, tend to invest in companies with high performance. In addition, an increase in inward investment might have a demand shock only on companies favored by institutional investors, thereby raising their share prices.

Accordingly, in another one of my analysis conducted along with Keisuke Nitta of Nippon Life Insurance Company, we used return on assets (ROA), which is not directly affected by share prices, as a performance measurement and excluded reverse causality as much as possible in our estimation. We found that the greater the percentage of shares held by foreign institutional investors, the higher the growth rate of ROA. This tendency was particularly conspicuous from 2002 through 2006.

For the past two decades, foreign institutional investors have accumulated information on Japanese companies and enhanced their monitoring capabilities. Japanese institutional investors also increased their independence from investee companies from 2000 onward. Moreover, as they grew more conscious of their fiduciary duty, they have become more active in exercising their rights as shareholders. Japanese and foreign institutional investors are in competition for fund management contracts from Japanese pension funds, and there are no longer any significant differences in their investment behavior. Thus, institutional investors' influence on corporate governance has been steadily increasing.

♦ ♦ ♦

If the views described above are correct, what are the future tasks necessary for Japanese corporate governance?

First, as far as leading Japanese companies are concerned, the establishment of a corporate governance arrangement is nearly complete.

Based on findings in its recent survey of corporate governance equality, the Asian Corporate Governance Association (ACGA) has appraised significant improvements made in disclosure and other governance-related activities in the Japanese market and voluntary efforts undertaken by Japanese companies. Fund managers of foreign institutional investors have also acknowledged that there is no serious problem in the form of corporate governance of Japanese companies. Although Japanese stocks appear to have lost their appeal to investors, it is not because Japanese companies failed to comply with or deviated from international standards in the corporate governance arrangement. One of the tasks for senior managers of Japanese companies is to explain elaborately and clearly to the market a vision of their strategy on how they plan to improve managerial efficiency and fundamentals.

Second, the task of corporate governance lies in how to create a mechanism that not only appropriately disciplines corporate managers but also ensures their discretion and enables them to increase corporate value. Japanese corporations have never had institutional ownership surpassing 50%. They are likely to have incentives to increase insider ownership, as evidenced by some Japanese companies reviving cross-shareholding after 2006. However, during the recent global recession, they suffered from substantial capital losses on their shareholdings, whereby many corporate insiders realized that cross-shareholding is not a rational option. Thus, another crucial task is how to design a mechanism to protect managerial discretion without relying on cross-shareholding.

Fortunately, following the collapse of Lehman Brothers, small and medium-sized and uninformed institutional investors have withdrawn from the Japanese market, and those remaining are, all-in-all, equipped with a well-established information infrastructure, and their behavior in terms of investment decisions and exercise of voting rights is relatively predictable. Going forward, it is hoped that an operative relationship will be formed between leading Japanese companies and institutional investors, both Japanese and foreign, based on mutual trust and dialogue.

Looking at the bottom 500 listed companies in terms of market value, we can see that the institutional ownership ratios generally remain low. For those companies, it is hard to expect institutional investors to play a central role in imposing discipline on corporate managers. Thus, a creditor bank and/or a buyout fund—an equity fund which invests in buyout opportunities and reorganizes businesses to raise corporate value—must play that role. Also, as those smaller listed companies have been slow to improve their boards of directors and remuneration systems, it is imperative for both to be revamped. In this regard, it is appropriate that the government (Financial Services Agency) introduced rules requiring listed companies to disclose information on remunerations for directors and cross-shareholdings, effective as of last year. Discussions are currently underway to allow a new form of governance structure, i.e. the establishment of an audit and supervisory committee under the board of directors, aiming at facilitating the appointment of independent directors. The introduction of such a committee would be quite useful for improving corporate governance among firms with smaller institutional ownership such as the bottom 500 listed companies.

* Translated by RIETI.

September 26, 2011 Nihon Keizai Shimbun