The Covid-19 pandemic and recent Russia-Ukraine war disrupted global supply chains and led to significant delivery delays, input shortages, and stockout risks. Firms exposed to such risks have been forced to rethink their production and inventory management from just-in-time to just-in-case. Using quarterly Japanese firm-level data, this column shows that relative to firms that purchase inputs only domestically, importers significantly and persistently increased their inventories of intermediate inputs. This suggests the possibility of a shift from just-in-time to just-in-case production after the pandemic.

Inventory plays an important role in international trade. Because of delivery lags and lumpy trade, importers face severe inventory management problems. It is reported that importing firms have approximately twice the inventory of firms that purchase materials only domestically (e.g. Alessandria et al. 2010). Supply chain disruptions during the pandemic have garnered attention from researchers and policymakers regarding the role of inventory as a buffer against input shortages. The previous study shows that among French firms exposed to the Chinese lockdown, those holding more inventories ex-ante performed better in the aftermath of the shock (Lafrogne-Joussier et al. 2022). Furthermore, Alessandria et al. (2023) examine the aggregate effects of supply-chain disruptions in the post-pandemic period and show that firms optimally hold inventories that depend on the source of supply, whether domestic or imported. However, little is known about global sourcing and inventory adjustments to supply chain shocks at the firm level.

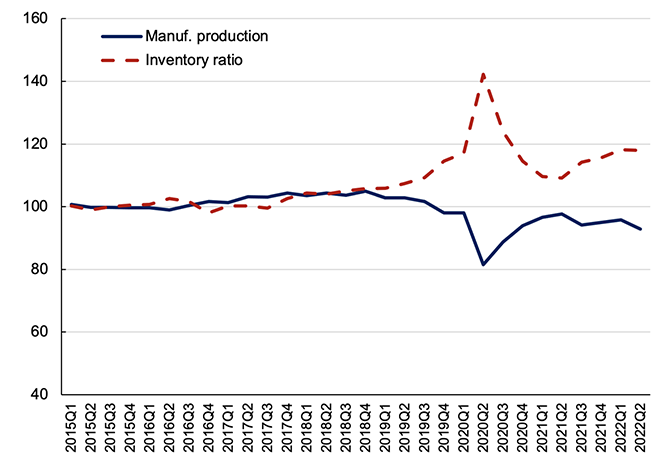

Figure 1 shows the quarterly movements in Japan’s manufacturing production and inventory ratio indices (seasonally adjusted) from Q1 2015 to Q2 2022. Manufacturing production was disrupted during Q1-Q2 2020 after the Japanese government took its first emergency measures in April-May in major economic regions. Meanwhile, inventories increased substantially, and their magnitudes were much larger than the decline in production. The inventory ratio declined quickly after Q2 2020 but it increased again after early 2021. It is worth noting that the inventory ratio remains persistently high even though production recovered by 2021. In early 2022, the inventory ratio further increased, probably because of the Shanghai lockdown and the Russia-Ukraine war.

Source: Indices of Industrial Production (IIP), Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI).

Motivated by this, in a recent paper (Zhang and Doan 2023) we explore a large-scale quarterly government survey of Japanese manufacturing firms over the period Q1 2015–Q2 2021 and examine firm-level inventory adjustments to supply chain shocks during the pandemic, focusing on firms that source inputs globally. Our data contain detailed quarterly information on each firm’s inventory of materials and supplies, work-in-process products, and finished goods. Japanese firms are famous for their well-organised just-in-time production systems and international production networks. Thus, they provide an ideal setting for studying firm-level responses (i.e. inventory adjustments) to supply chain shocks.

Importers increase inventories after the pandemic

We first show that before the pandemic, relative to firms that purchase inputs only domestically, importing firms tend to have higher inventory ratios (inventories over sales) and stocks in materials and supplies, work-in-process (intermediate goods), and finished goods, even controlling for firm size. While this relationship has been documented by Alessandria et al. (2010) for Chilean firms, we show that it is also present for Japanese manufacturing firms.

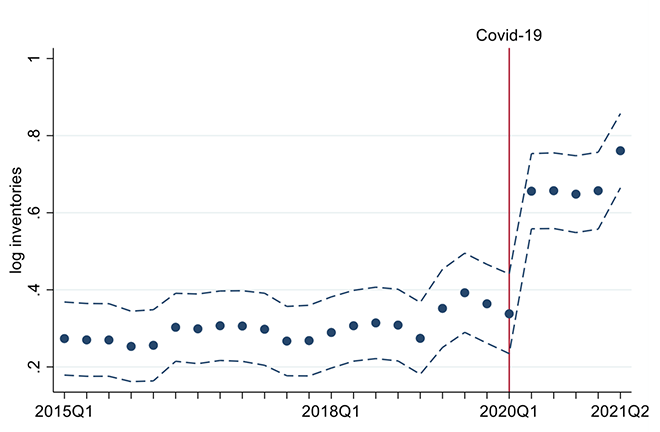

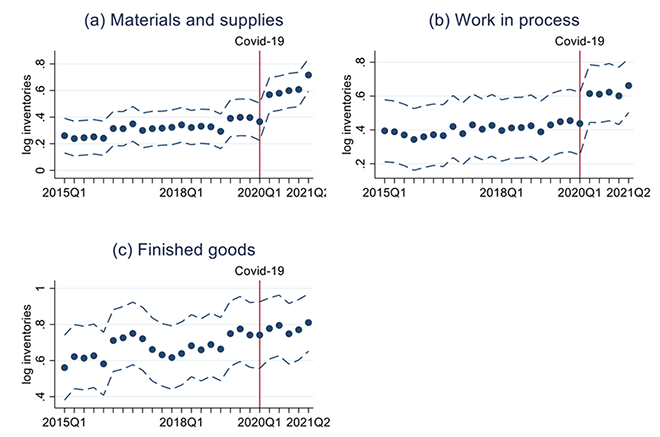

After the pandemic, relative to non-importers, importers significantly and persistently increased their total inventories (Figure 2) and inventories in materials and supplies, work-in-process, and finished goods, respectively (Figure 3). Furthermore, it is worth noting that there are substantial heterogeneities across all three types of inventories within each industry. For example, in the automobile industry, with prevailing just-in-time production and inventory management, work-in-process inventories (intermediate goods) exhibited a sharp increase during the pandemic, suggesting the importance of parts and components in this industry. These results suggest the possibility of a shift from just-in-time to just-in-case production during the pandemic.

[Click to enlarge]

Import reliance and supply chain disruptions

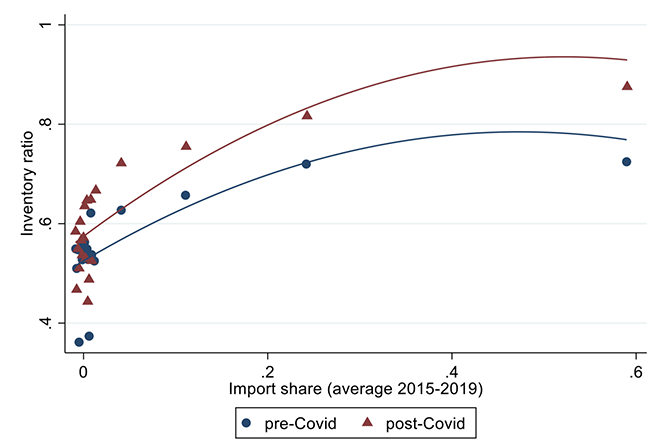

We show that importers significantly and persistently increased their inventories, especially for firms with ex-ante higher import share and (multinational) firms that experienced supply chain disruptions in China. Figure 4 shows the relationship between ex-ante import share (defined as the average share of imported inputs in total sourcing from 2015 to 2019) and inventory ratio for the pre-Covid and post-Covid samples. There is a strong positive correlation between ex-ante import share and inventory ratio in both pre-Covid and post-Covid periods. Firms tended to increase their inventory holdings after the pandemic, especially those that relied heavily on imported inputs.

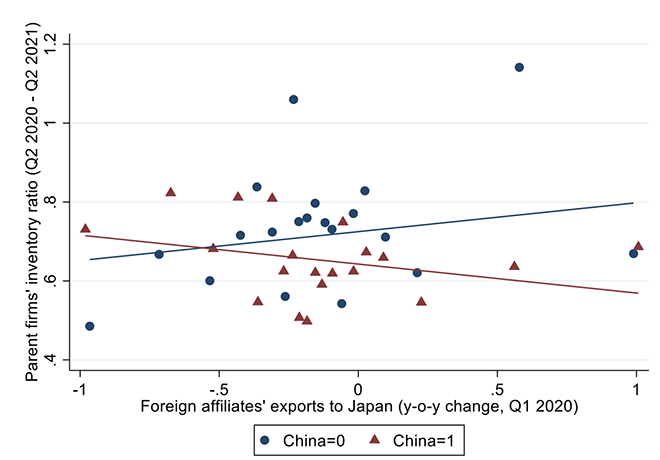

Figure 5 shows the relationship between supply chain disruptions and ex-post inventory holdings. The horizontal axis represents the year-on-year changes in foreign affiliates’ exports to Japan in Q1 2020, and the vertical axis represents parent firms’ inventories after Q2 2020. The red triangles and fitted lines show that the lower the growth of exports to Japan by manufacturing affiliates in China in Q1 2020, the larger the inventories held by parent firms after Q2 2020. In other words, Japanese multinationals that experienced a sharp drop in sourcing inputs from China tended to increase their inventories after supply chain shocks. In contrast, the blue dots and fitted line show the opposite pattern: the higher the growth of exports to Japan by manufacturing affiliates in other countries in Q1 2020, the larger the inventories held by their parent firms after Q2 2020. These results suggest that supply chain disruptions during the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic had a large and persistent effect on importer inventory management.

We further consider the potential factors affecting inventories, including the industry upstreamness in the production network, the prefecture-level severity of the Covid-19 infections, industry-level input and output prices, firm-level financial constraints, and firm-level uncertainties over economic and business outlooks. Even controlling for these factors, results show that importers always tend to hold more inventories relative to importers after the pandemic.

Concluding remarks

Our study is expected to provide policy implications for the debate on the robustness and resilience of supply chains by providing evidence of firm-level adjustments to supply chain shocks and the relationship between global sourcing and inventory holdings. Relative to firms that exclusively purchase inputs domestically, importing firms tend to hold larger inventories, even when controlling for firm size. More importantly, after the pandemic, importers reacted to potential input shortages by increasing their inventories of materials and suppliers, intermediate inputs, and finished goods. This is more prominent for firms with higher ex-ante import share and multinational firms that experienced supply chain disruptions in China. These results suggest the possibility of a shift from just-in-time to just-in-case production after the pandemic. Note that due to data constraints, we cannot observe whether a firm adopts just-in-time or just-in-case inventory. However, firms that rely heavily on imported inputs, and firms that experience supply chain disruptions do increase their inventories of intermediate inputs after the pandemic despite large carrying costs.

Inventories can act as buffers against supply chain disruptions and input shortages during pandemics and other supply chain shocks. However, increasing inventory is accompanied by increasing costs, which are crucial for firms with financial constraints. Thus, policies that relax financial constraints are required, especially for firms relying on international supply chains and imported inputs. More importantly, policies in the post-pandemic era should support business efforts to build robust and resilient supply chains. It is also worth noting that because our sample period is until Q2 2021, it is premature to conclude that manufacturing firms have completely shifted from just-in-time to just-in-case production. It is necessary to monitor firm-level inventory adjustments and the macroeconomic inventory cycle.

Authors’ note: The main research on which this column is based (Zhang and Doan 2023) first appeared as a Discussion Paper of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) of Japan.

This article first appeared on VoxEU on September 1, 2023. Reproduced with permission.