The service sector accounts for much of the output of many advanced economies, and maximising the sector's output while also minimising regional disparities is an important policy challenge. This column analyses productivity in service sectors in Japan, focusing on economies of urban density. The higher the employment density of the cities in which service firms are located, the higher their productivity, but firms relocating to such cities negatively impacts regional disparity. Further, considerable differences in productivity improvements among sectors indicate there certain industries should be promoted in large cities, and others in smaller cities with lower employment density.

The service sector accounts for more than 70% of the gross domestic product (GDP) in advanced economies. Improving the productivity of the service sector is a key policy issue for lifting the economy's potential growth rate. In Japan, for example, the government's 2015 revision of the Japan Revitalization Strategy states that "stimulating the service industry and raising its productivity" is a major mid-term economic policy.

At the same time, reducing regional disparity in economic performance has been an important policy issue in every country. Place-based economic policies such as the Empowerment Zone in the United States and the Structural Funds in the European Union are well-known examples of such attempts (see Kline and Moretti 2014, and Neumark and Simpson 2015, for surveys). In Japan, the Overall Strategy on Vitalizing Local Economies was determined by the Cabinet in 2014 to revitalise regional economies.

However, we should be aware that spatial distribution of the population and economic activity greatly affects the productivity performance of service industries. In other words, reallocation of economic activity toward densely populated large cities is inevitable in order to improve productivity at the national level, under the trend of a service-oriented economy. As a result, improvement in productivity in the service industry may widen the economic disparity among regions. In order to assess the magnitude of this possible trade-off, quantitative studies focusing on service industries are essential.

Knowledge-intensive business services in advanced countries

In principle, large densely populated cities have a strong advantage as a location of service industries, because service industries are characterised as 'simultaneous production and consumption'. However, empirical studies on the productivity of the service industry from the viewpoint of agglomeration economies have been lagging behind those on the manufacturing industry. Glaeser and Gottlieb (2009), a representative survey on agglomeration economies, state that modern cities specialise in service industries where face-to-face contact is important, and that analysis of agglomeration economies in service industries therefore is a high priority issue to understand the role of cities in modern economies.

Among a wide-variety of service industries, knowledge-intensive business services (KIBS) are growing rapidly in advanced economies. KIBS, which mainly produce services that are used as intermediate inputs by businesses, are characterised by the high intensity of knowledge and highly skilled employees. Although a concrete definition has not yet established, KIBS include computer-related services (e.g. software and information processing), research and development services, and business services (e.g. legal, accounting, and advertising). Overall, these services are developed in advanced economies and hire employees with high education levels. The industries themselves not only have strong growth potential, but also affect the performance of other industries such as manufacturing, which use their services as intermediate inputs (e.g. see Barone and Cingano 2011, Bourles et al. 2013, Boix-Domenech and Soler-Marco 2015).

Recent research on value-added trade using world input-output tables also indicates that intermediate input services play a very important role in terms of international competitiveness. Numerous services are embedded in traded manufactured products, and, typically, advanced countries have a comparative advantage in these intermediate input services, especially knowledge- and skill-intensive business services (e.g. Timmer et al. 2014, Johnson 2014).

A relatively small number of past studies estimate the effect of agglomeration economies for business services. These studies generally find evidence of advantages in knowledge-intensive services in densely populated urban areas (e.g. Graham 2009, Combes et al. 2012, Maré and Graham 2013, Meliciani and Savona 2015). However, the number of studies focusing on KIBS is limited, and a study on KIBS in Japan has yet to be conducted.

Employment density and productivity of KIBS

In this context, I empirically analyse productivity in knowledge- and information-intensive business services in Japan, with a focus on economies of urban density (Morikawa 2016). Specifically, I estimate economies of density using establishment- and firm-level micro data for 14 narrowly disaggregated business service industries, such as software, data processing services, internet-based services, publishers, design businesses, and advertising agencies. The data for 2010 and 2013 are taken from the Survey of Selected Service Industries performed by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry.

These 14 business service industries account for more than 1.5 million workers and about 36 trillion yen in sales (2012 Economic Census for Business Activity). These industries are characterised by their high level of skill intensity. The percentages of employees who have at least a four-year university degree is 60.8% in the information services industry, 57.3% in the information production and distribution industry, and 58.0% in advertising agencies. These figures are more than twice as high as the ratio for the manufacturing industry (25.5%).

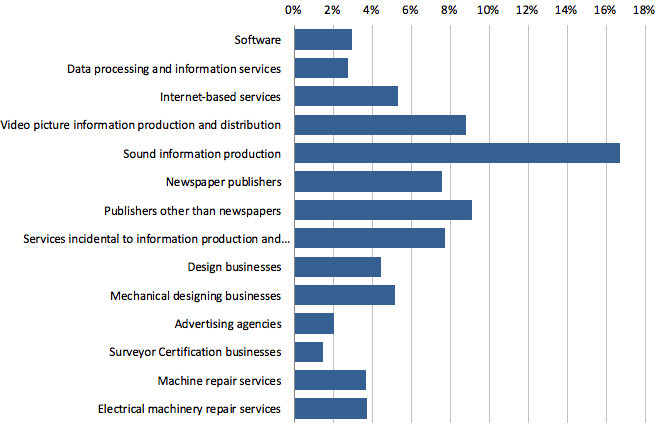

According to the estimations, the higher the employment density of the municipalities in which these services are located, the higher the productivity of establishments and firms (Figure 1). On average, doubling the employment density of a municipality is associated with around 6% higher labour productivity for service establishments and firms located there. However, this relationship differs considerably depending on the industries. In the knowledge and information creating service industries (e.g. video picture information production and distribution, sound information production, and publishers), there are great economies of urban density. On the other hand, industries where information and communication technologies overcome the barrier of distance (e.g. software services, data processing, and information services) and sectors where accessibility to manufacturing establishments is important (e.g. machine repair services) do not necessarily gain a great advantage by being located in large cities.

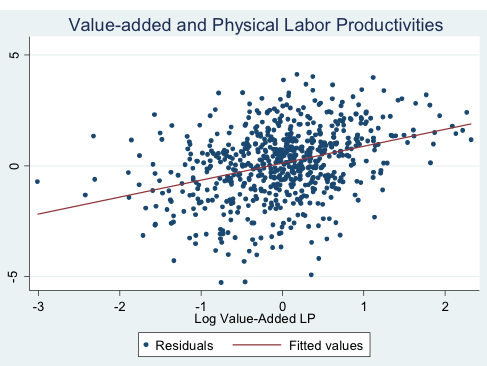

Regarding publishers, for whom quantity-based productivity measures are available, we can see a positive correlation between value-added productivity and physical productivity (Figure 2). Interestingly, we observe greater economies of urban density when using a measure of physical productivity than when using a measure of value-added productivity. Specifically, the measured elasticity of physical productivity with respect to employment density is about 1.6 times large, compared with the elasticity in value-added productivity.

Policy implications

These findings indicate that urban density plays a key role for the knowledge- and information-intensive business services that are likely to support future economic growth, suggesting that policies to maintain concentrations of employment in large cities are desirable in the context of the declining population in Japan. However at the same time, such policies may deteriorate the disparity of economic performance among regions.

The fact that there are considerable differences in density elasticity depending on the sector tells us that there are service industries to be promoted in huge cities such as Tokyo and Osaka, and others that can be promoted in small and medium-sized cities with relatively low employment density. For example, it would be difficult for publishers to raise their productivity in small and medium-sized cities, but sectors in which information and communication technologies overcome the barrier of distance and sectors where accessibility to manufacturing establishments is important do not necessarily gain a great advantage by locating in large cities.

Editors' note: The main research on which this column is based appeared as a Discussion Paper of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) of Japan.

This article first appeared on www.VoxEU.org on July 10, 2016. Reproduced with permission.