As a result of the U.S.-China showdown and the Russian invasion of Ukraine, discussing geopolitical issues has become all the rage in the media.

What we must keep in mind is that geopolitical discussions that emphasize confrontation has become significantly disconnected from economic realities. Of course, it is important to hold in-depth discussions on matters of economic security amid the growing geopolitical tensions. However, economic activities still go on and supply chains continue to function. To consider the future of Japan’s relationships with other Asian countries, particularly members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, we must first recognize that fact.

Although the decoupling of supply chains from China has made some progress with respect to some high-tech products using sensitive technologies, batteries, and rare earth-related products, the impact has so far barely appeared in aggregated trade statistics.

U.S. exports to China, particularly grains, energy, and semiconductors, increased from 2020 to 2021. Japanese exports to China also increased steeply in 2021, driven by exports of electronic parts and machinery. In recent years, Japan has strengthened export controls, but the number of export permits granted in 2020 increased by more than 10% to over 20 million, as the electronification of customs procedures has proceeded at the same time (according to data compiled by the Ministry of Finance).

Even though the division between China and the Western world may deepen further, the predominant view is that the decoupling will remain partial. The important thing to do is maintain economic dynamism and investment appetite even while guarding against future geopolitical crises.

◆◆◆

In May 2022, the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), a U.S.-led plan to create a new economic area, was launched. In addition to Japan and the United States, the 14-nation IPEF includes seven of the 10 ASEAN member countries—excluding Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar—and South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, India and Fiji.

The IPEF is comprised of four policy pillars: trade; supply chains; clean energy, decarbonization and infrastructure; and tax and anti-corruption. In June and July, in-person and online ministerial meetings were held. To make this framework effective, active engagement by ASEAN countries in particular is essential.

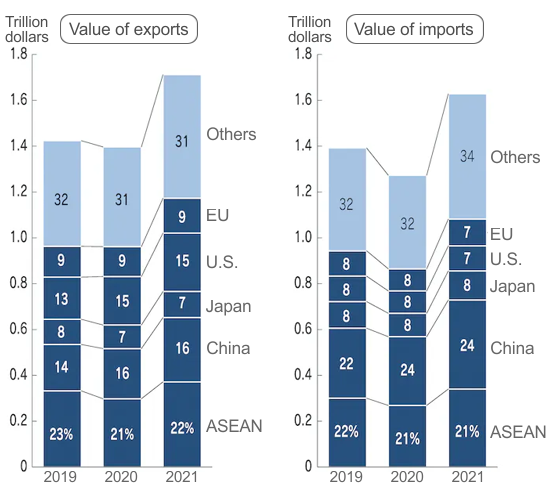

The figure below shows the total value of goods exports and imports for all of the ASEAN countries in 2019-2021. Trade value declined only slightly in 2020 and recorded strong growth in 2021. In particular, the decline in exports was insignificant because of ASEAN countries’ successful early efforts to contain the COVIV-19 pandemic and also because the countries captured increased demand for products related to remote work and stay-at-home restrictions. Since the beginning of 2022, the ASEAN region has been hit by various economic shocks, including the expansion of infections due to new variants of COVID-19, the impact of China’s zero-COVID policy and the food and energy price upsurge, but on the whole, the ASEAN economy has maintained a sufficient level of dynamism.

A breakdown of ASEAN trade by trading partner shows that the share of intra-ASEAN trade in the region’s overall goods trade is in the lower 20% range in terms of both import and export. On the export side, major trading partners outside the region include China and the United States (with shares of 16% and 15%, respectively, in 2021), and on the import side, the largest trading partner outside the region is China (a share of 24% in 2021). Trade with Japan is small, with the Japanese share at 7% of ASEAN’s overall exports and at 8% in the region’s overall imports. When it comes to non-trade economic relationships, including direct investment and finance, Japan and other Western countries are more strongly involved with ASEAN. Nevertheless, it is clear that China has a huge presence over the ASEAN region.

The ASEAN countries well understand the potential policy risks related to China, and they are therefore engaging in a balancing act by deepening their economic ties with Western countries led by the United States. On the other hand, they wish to avoid being forced into a situation where they have to choose between the two superpowers.

The IPEF provides an important opportunity for Japan to show how it intends to engage with Asia, including ASEAN, in the future. One constraint is the absence of tariff concessions under the IPEF due to the United States’ domestic circumstances. Even so, Japan should not leave it to the United States to fix the details of the IPEF agreement but make efforts to ensure ASEAN engagement.

◆◆◆

The IPEF is expected to allow member countries to choose whether or not to participate on a sector-by-sector basis, unlike under the framework of free trade agreements, which in principle require a comprehensive agreement encompassing multiple sectors. Now may be the time to try something bold. One good idea would be to attract partners under a two-pronged approach: this would begin by enforcing a binding agreement among countries willing to make a commitment, but also offering a more flexible partnership arrangement in order to bring in more partners. The Trans-Pacific Economic Partnership (TPP) may be regarded as one of the agreements fallen into the former category.

As for the details of the IPEF agreement, one option would be to clearly separate purely economic agendas from economic security agendas. That would dispel possible partners’ worries that the United States, which is pushing the “friend-shoring” initiative to develop supply chains among trusted partner countries, may pressure them to make a U.S.-or-China choice.

Economic agendas should include attractive inducements to ensure that the ASEAN countries remain interested. “Digital” and “green” are the keywords. Digital rules, including the provision for free cross-border data flow and the prohibition of data localization, may be difficult for some countries, such as India, to accept immediately, but the first step should be taken by countries that are willing to accept the rules. The e-commerce chapter of TPP and the Japan-U.S. Digital Trade Agreement would serve as a model for the rules. It is also essential to ensure the effectiveness of the rules as international standards by clearly defining the scope of exceptions to public policy and exceptions to national security and by including rules on government access to private data.

In addition, it is necessary to propose cooperation for the promotion of digital transformation (DX) and for activities to resolve the digital divide, including infrastructure development, technical assistance, human resource development, and support for entrepreneurship. The ASEAN countries are also strongly interested in sectors such as green technology and energy and environmental transitions, and Japan and the United States have something to offer in those sectors. Japan and the United States must promote cooperation with ASEAN by taking advantage of their own technological expertise and high-quality products and services.

Regarding economic security agendas, for the moment, the important thing to do is to acknowledge individual countries’ respective positions and to take the first step by embracing countries that are willing to accept the proposed agendas. Amid the growing geopolitical tensions, ASEAN will have to take action in some sectors. For example, with respect to trade controls related to supply chains, the extraterritorial application of the U.S. export control laws affects companies located within the ASEAN region. Moreover, import restrictions related to human rights violations, which the United States and European countries are moving to legislate, will also require some kind of action.

Strengthening cybersecurity is also important. Development of cybersecurity-related systems will become necessary for the ASEAN countries as well, and therefore, there is room for them to deepen their engagement in economic security.

The fundamental problem is the decline in the Japanese economy’s position relative to other economies. As Japan has less and less to offer in the eyes of other Asian countries, it has become difficult to have matters of interest for Japan reflected in the IPEF.

For Japan as well, it is important to promote economic agendas and economic security agendas at the same time. Japanese companies have already made much progress in pursuing the “China plus one” strategy to diversify supply chain operations outside China. If there are important goods and resources for which there are absolutely no non-China alternatives, then it would be a good idea to help realign production operations while maintaining appropriate profitability as a defensive approach, in order to avoid future supply disruptions.

However, it is not easy to pursue a more aggressive approach, such as developing tools of “economic statecraft” to erode adversarial countries’ competitiveness by decoupling supply chains, or to exercise political influence over them through economic means. As a first step, Japan should look squarely at the decline in its own international competitiveness and mobilize human and physical resources to strengthen international competitiveness under free market competition.

* Translated by RIETI.

August 3, 2022 Nihon Keizai Shimbun