| Date | January 18, 2011 |

|---|---|

| Speaker | FUJITA Masahisa (President and Chief Research Officer, RIETI) |

Summary

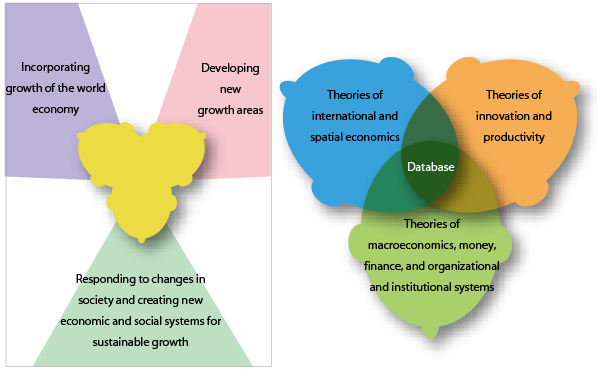

The Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) was founded on April 1, 2001 as an incorporated administrative agency (IAA) staffed by employees of a non-public servant status, building on the activities of its predecessor, the Research Institute of International Trade and Industry, established in 1987 as a functional unit of the now-defunct Ministry of International Trade and Industry. In its initial medium-term plan period covering the five years from April 2001-March 2006, RIETI established nine Research Clusters as a framework for organizing its research activities under the leadership of then President and Chief Research Officer Masahiko Aoki, a professor emeritus of Stanford University. Similarly, RIETI has defined four Major Policy Research Domains as a coherent framework for its second medium-term plan period (April 2006-March 2011). In the forthcoming third medium-term plan period beginning in April, we take it as our mission to conduct theoretical and empirical research to create a grand design for putting the Japanese economy on a growth path. As defined in our new medium-term objectives, we will pursue research by always keeping in mind the following three Priority Viewpoints of economic and industrial policies: 1) incorporating growth of the world economy, 2) developing new growth areas, and 3) responding to changes in society and creating new economic and social systems for sustainable growth.

The Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) was founded on April 1, 2001 as an incorporated administrative agency (IAA) staffed by employees of a non-public servant status, building on the activities of its predecessor, the Research Institute of International Trade and Industry, established in 1987 as a functional unit of the now-defunct Ministry of International Trade and Industry. In its initial medium-term plan period covering the five years from April 2001-March 2006, RIETI established nine Research Clusters as a framework for organizing its research activities under the leadership of then President and Chief Research Officer Masahiko Aoki, a professor emeritus of Stanford University. Similarly, RIETI has defined four Major Policy Research Domains as a coherent framework for its second medium-term plan period (April 2006-March 2011). In the forthcoming third medium-term plan period beginning in April, we take it as our mission to conduct theoretical and empirical research to create a grand design for putting the Japanese economy on a growth path. As defined in our new medium-term objectives, we will pursue research by always keeping in mind the following three Priority Viewpoints of economic and industrial policies: 1) incorporating growth of the world economy, 2) developing new growth areas, and 3) responding to changes in society and creating new economic and social systems for sustainable growth.

Now, let me show off my talent as a word riddle creator--"Totonoimashita (Here's one)," --borrowing one of last year's most popular catchphrases in Japan. Referring to RIETI's third medium-term plan period, I am reminded of the statue of the three-faced Ashura, a national treasure of the Kofukuji temple in Nara. The reason for that is because both of them look at the world from three viewpoints. What is important here is that unlike the heads of the Yamata no Orochi "Eight-Forked Serpent," a legendary Japanese dragon, the three faces of Ashura--hence the three viewpoints of RIETI--are not separated from one another. Instead, they are firmly united and function as a unified whole, whereby information and expertise obtained from each viewpoint will be shared and blended within a single brain, and yet they will pursue, develop, and maintain theories unique to their respective fields. Thus, there are three sets of theories--one of international and spatial economics, one of innovation and productivity, and one of macroeconomics, money, finance, and organizational and institutional systems--and suppose that we have a sort of "database" of knowledge and expertise at the intersection of the three sets. Such is the image I have in mind. Under this formation, we would like to proceed with our research activities in our third medium-term plan period.

Today, I would like to discuss the progress of globalization and large-scale structural changes in the world economic map from the viewpoint of spatial economics in which I specialize. Thereafter, based on these observations, I would like to offer my view on the economic growth that has been achieved in East Asia and the restructuring of the global and Asian economies toward a more balanced development. I will also speak about the diversity and culture of what I call a knowledge-creation society, based upon which I will present my personal thoughts on the reconstruction of Japan in the era of globalization and knowledge.

Spatial economics

Traditionally, there were three areas of economics focusing on geographical space--urban economics, regional economics, and international trade theory. Then, in the era of a borderless economy, a new economic geography, or spatial economics, emerged through the generalization and innovative development primarily of microeconomic theories of cluster formation. This marks a distinct difference from Michael Porter's cluster theory in that general equilibrium theory and a dynamic general equilibrium approach are consistently applied in spatial economics.

The integration of Europe that began in 1990 served as a momentum for the significant development of spatial economics. The elimination of national borders within the European Union, then consisting of 15 member states (EU15), marked the beginning of the EU integration process. In order to draw an economic map of a borderless Europe, it was necessary to integrate urban economics, regional economics, and international economic theory. For about a decade thereafter, a number of researchers undertook studies to find a new theory. One of the outcomes of such efforts is The Spatial Economy, in which Paul Krugman, Anthony Venables, and I developed a systematic theory for explaining economic activity.

As part of the 50th Congress of the European Regional Science Association in Jonkoping, Sweden, in August 2010, a roundtable commemorating the 10th anniversary of the publication of The Spatial Economy was held and the three of us discussed spatial economics under the chairmanship of Jacques Thisse. In the course of my discussion today, I would like to refer to what we discussed at the roundtable session.

Dynamic changes in the global economic map are the research target for spatial economic studies. Remarkable developments in transportation technologies and information and communication technologies (ICTs) have dramatically reduced broadly defined transportation costs, including those for transporting people, goods, money, and information. A significant drop in transportation costs has become the engine for transforming the global economic system, thereby bringing about two seemingly contradictory phenomena--globalization in the form of eroding national boundaries and localization in the form of formation of local economic zones and/or increasing the importance of cities and regions--at the same time.

The underlying idea is this: There are two types of forces, namely, agglomeration forces (centripetal forces) that encourage the concentration of economic activities in a certain location and dispersion forces (centrifugal forces) that scatter the concentration. Through the interplay between these two opposing forces arises the process of self-organization, leading to the creation of stable spatial structure. When the stability is lost due to the emergence of a new technology or changes in the situation, the shift to a new spatial structure occurs. In the 19th century, the Industrial Revolution occurred in Europe. The 20th century, which can be described as the era of oil and automobiles, saw a remarkable development of the United States. Then, from around the latter half of the 20th century, Asia including China and India emerged as a new growth center of the world. Capturing those dynamic changes is the basic aim of spatial economics.

Tokyo is inhabited by approximately 30 million people. When such concentration occurs, land prices go up and so do wages, which in turn generates dispersion forces as a natural course of events. But why have so many people come to live in Tokyo? The natural geographic advantage of being located in the Kanto Plain, the largest plain in Japan, is one reason. However, what is of crucial importance is the working of endogenously generated agglomeration forces. Thus, how to explain such endogenous agglomeration forces is the theoretical focus of spatial economics research.

The biggest factors behind endogenous agglomeration forces are human activity to produce consumption and intermediate goods and the diversity or differentiation among humans. When those factors are combined with economies of scale and indivisibilities as well as with human and business mobility, forces for agglomeration and innovation occur at a regional level.

The lock-in effect of agglomeration has both positive and negative sides. In a short-term horizon, agglomeration generates positive externalities with the clustering of people fostering economic growth. In the long run, however, the negative side of the lock-in effect comes into play, making it difficult for individuals to make changes on their own due to externalities and the problem of the entire system. Such is the state in which Japan finds itself today. In order to overcome the ongoing stalemate, it is necessary to create new externalities. Bringing in new talents and knowledge to achieve that end can operate as an economic policy in a broad sense.

Diversity and agglomeration forces: A case of cultural industry

Diversity is indispensable to increasing agglomeration forces. When people and their activities are diverse and highly differentiated, direct competition (most importantly, price competition) can be avoided, whereby the overall level of complementarity will increase. Then, even when people and activities concentrate in a certain geographic region, productivity, ability to attract customers, and creativity of these people or their activities continue to increase through externalities, thereby bringing greater net gain for the region as a whole. Now, let me explain this further by taking the creative industry as an illustrative case.

In a utility function, greater diversity (or an increase in variety) leads to an increase in utility. Needless to say, variety does not increase indefinitely as economies of scale come into play. I will skip explaining this in detail, but I would like to cite the revolution of the so-called "gal industry" in Japan as an illustrative example. This is a new industry revolving around youth fashion. Now, I am not talking about European-style high fashion. Instead, I am talking about what is referred to as "fast fashion," a type of cheap and fast fashion for youth, in which a complete set of clothes and accessories to go with them, including hair clips and shoes, can be bought for 30,000 yen. Shibuya 109, a shopping complex in Tokyo and the cradle of this particular fashion revolution, has now come to be called the "temple of gal fashion," attracting nine million shoppers every year from around the world and particularly from neighboring Asian countries. Each of the approximately 120 shop tenants in the building is small with a floor space of only about 50 square meters. However, the average annual sales per shop is about 300 million yen, with combined sales of all shops in the complex amounting to about 40 billion yen, a size on par with that of a major department store.

The presence of an unparalleled variety of items to choose from is the very magnet attracting customers. Shops in Shibuya 109 sell only their original items, and more than half of the items on the shelves are replaced in a month. Because of the rich diversity of products within each shop as well as across different ones housed in Shibuya 109, they have been able to avoid direct competition with each other and increase mutual complementarity.

Cecil McBee, one of the most sought-after fashion brands in Shibuya 109 with annual sales of one billion yen, does not have any designer. Shop clerks--there are about six of them at the Cecil McBee shop in Shibuya 109--are the ones who make plans for new products and place orders with apparel manufacturers. Within a month after the commencement of product planning, they start selling the new products. Shop clerks typically serve as fashion models for customers to emulate, though many of these shop clerks used to be customers. That is, someone who used to frequent a shop as a customer has become a shop clerk and is now serving as a model for customers. The important point is that all players--customers, shop clerks, product planners, and sales and marketing staff--are collectively coming into play to create original products and continuing to replace older items with newer ones.

Meanwhile, even though shops are not in direct competition with each other, they compete indirectly. With these 120 or so shop tenants in Shibuya 109 earning an average of 300 million yen in annual sales, rent for store space is extremely high and nearly one-third of shop tenants are replaced every year. Therefore, driven by such an overwhelming agglomeration force, a portfolio of shops housed in Shibuya 109 continuously turns over with new product development and creation simultaneously taking place all the while.

Now, though this is specifically about the case of the apparel industry, various related industries are sprouting in Tokyo, with the fashion magazine business as an example. When you go into a convenience store, nearly half of the magazines you will see being sold there are fashion magazines, and they are creating synergies in very diverse downstream sectors of the economy. For instance, it is not rare for a former magazine fashion model to turn into an actress starring in a TV drama. Also, synergies are being created not only within but also outside the national boundaries. In 1993, a couple of Chinese women purchased the copyrights to publish the Chinese edition of Ray, a popular women's magazine in Japan, from Shufunotomo Co., Ltd. With roughly half of the content replaced with original articles specifically targeting Chinese readers, Rayli, as the Chinese edition is titled, is priced at 20 yuan per issue and has monthly sales of 1.05 million issues. As exemplified by this, the local language editions of Japanese fashion magazines are being circulated internationally and across many Asian countries, including South Korea, Thailand, and the Philippines.

Now, let me cite another example, a Japanese pop group called AKB48. Indeed, the explosive popularity of AKB48 is also related to diversity. Each member of AKB48 has overwhelming power within the framework of "focused diversity." Tickets to AKB48's live performance at its own theater in Akihabara, Tokyo, are distributed only to those who have applied for and won a lottery in advance. It is said that there is only a one out of a hundred chance of winning a ticket. This can be viewed as a new business model based on the strategy of focused diversity, which has turned out to be highly successful by demonstrating such an overwhelming power to attract customers.

In contrast, those in the South Korean pop music business, known as K-pop, typically pursue a strategy targeted at international markets from the very beginning as they find the domestic market too small. For instance, each member of Girls' Generation, a nine-member girl group, speaks Japanese, English, and Chinese. From the viewpoint of spatial economics, while the large domestic market of Japan is what makes J-pop idols so powerful, the small domestic market of South Korea is a driving force for K-pop idols to go into overseas markets by learning foreign languages such as English and Japanese and thereby reducing the transportation costs to such markets. Meanwhile, because of the home-market effect, whereby a market with the greatest demand tends to attract a more than proportionate share of demand, such industries as fashion, entertainment, media, culture, and tourism concentrate in large cities--Tokyo in the case of Japan. Such clustering serves as an additional driving force by making the city more luring and bringing in even more young people.

In the fundamental theory of spatial economics, we can see the following four important elements: (1) spatial factors such as location, distance, and transportation costs; (2) firm-level economies of scale through the home-market effect; (3) diversity; and (4) history-dependent lock-in effect.

Declining transportation costs and the development of information technology

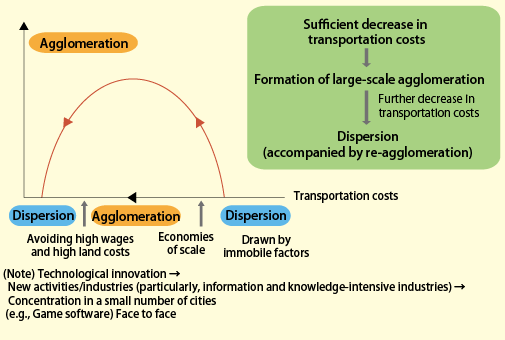

What does a decline in transportation costs mean in terms of spatial economics? Broadly defined costs of transporting people, goods, money, and information have significantly declined over the years. It is often said that as information technology continues to develop, we will be brought into a world where people can communicate with each other over mobile phones at any time and any place and, in such a world, there will be no need to gather and meet in a physical space. Some people say that this would mean the death of cities and agglomerations. However, the effects of declining transportation costs are not that simple but are represented by an inverted U curve.

From a chart with transportation costs on the X axis and agglomeration of activities on the Y axis, we can see that when transportation costs are high, production activities are dispersed, whereby locally produced products are inevitably consumed in the area because even if you produce certain products in large volume in one place, you would not be able to export them. One example of such situation can be found in Japan's postwar reconstruction, in which steel was in high demand all across the country. Since the nation's transportation network had been destroyed by the war, steel was produced in various locations such as Muroran in Hokkaido and Kamaishi in Iwate Prefecture. However, steel is the type of product for which economies of scale are critically important. Thus, with the development of transportation networks, steel production began to concentrate in areas near major cities such as Tokyo, Nagoya, and Osaka. In particular, Yawata Works in Kitakyushu, Fukuoka Prefecture, concentrates on rail production. So, when transportation costs are lowered to some extent, manufacturers begin to concentrate production activities to areas of high demand and, from there, export to areas with lower demand. When this process continues and the concentration of activities grows to an excessive point, the dispersion of activities will begin as manufacturers seek to avoid higher labor and land costs. But what I mean to say is that, initially, there must be a sufficient decrease in transportation costs and only then can large-scale agglomeration be formed.

A further decline in transportation costs will prompt activities to be dispersed accompanied by the re-agglomeration of activities elsewhere. This, however, does not mean that the original place of agglomeration will be emptied out. Information and knowledge-oriented industries are bound to form agglomeration in cities because face-to-face communication is indispensable in these industries.

Another interesting subject of spatial economics is the "siphoning effect." The size of a market is determined by the product-specific maximum allowable distance, i.e., the maximum distance customers are willing to travel to obtain a specific product. For instance, ordinary clothes shops, grocery stores, and other stores selling items that are not highly differentiated can be found not only in large cities but also elsewhere at short intervals, whereas fashionable boutiques and high-class restaurants are located at greater distances from each other, indicating a greater size of the market. In the case of dealing in extremely differentiated goods, as in the gal industry and international financial institutions, the size of the market is even greater. Once agglomeration is formed in Tokyo, there will unlikely be another in Japan. In other words, the whole country is a single market area. What is important here is that the product-specific maximum allowable time can be magnified when transportation costs decline with the advancement of information and transportation technologies, as has been the case with the emergence of shinkansen bullet trains and airplanes.

A typical example of the siphoning effect can be seen in Osaka after the Tokaido Shinkansen began operations between Tokyo and Osaka in 1964, as Osaka failed to change its industrial structure and many companies moved their headquarters or head office functions to Tokyo. Initially, a round trip between Tokyo and Osaka took about eight hours and companies needed to keep head office functions both in Tokyo and Osaka. However, as the shinkansen became faster and it became easier to make a round trip between the two cities within a day, it was no longer thought to be necessary to have two headquarters. Then, as a natural course of events, functions in the smaller of the two were siphoned to the larger. This siphoning effect dealt a significant blow to Osaka. Today, concerns are being voiced that Japan, in its relation with China, may follow the same fate as Osaka and lose entire manufacturing industries to its giant neighbor. In order to maintain large agglomerations even after transportation costs have been significantly lowered, we must, at all costs, differentiate activities and agglomeration. How we can strengthen agglomeration forces hinges on how we can create and maintain unique, differentiated activities.

Globalization and world economic growth

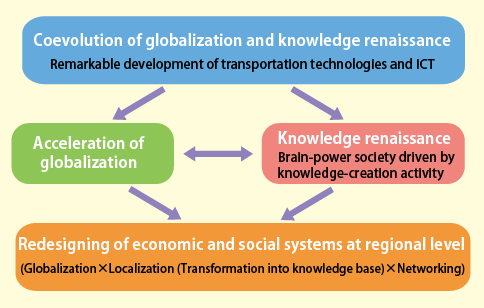

Now, let's take a look at globalization and world economic growth from the viewpoint of spatial economics. Declines in broadly defined transportation costs have been the engine of global economic system reform. A significant decline in transportation costs prompted globalization and localization, leading to economic growth across the world and bringing major structural changes in the map of the global economy.

According to the latest White Paper on International Economy and Trade, transportation costs have been on a continuous decline since 1930. In absolute terms, however, "trade costs, broadly defined, are large," as J. E. Anderson and E. van Wincoop noted in the Journal of Economic Literature. A typical toy manufactured in China is sold to American consumers at a price 170% higher on average than the production cost. In other words, the cost of transportation is 1.7 times that of production. In an extreme example, Sekai-ichi, a Japanese apple grown in Aomori Prefecture and sold for only about 300 yen there, is sold at 2,100 yen per piece at an Isetan department store in Tianjin, China. Being a perishable food might be one reason, but the biggest reason for the seven-fold price difference is either the high degree of differentiation or the fact that apples of this particular variety cannot be grown in other countries or regions. Another often-cited reason is the presence of wealthy consumers. Although China's per capita gross domestic product (GDP) is only one-tenth that of Japan, income disparities are so enormous that there exist a significant number of consumers who are willing to pay such a high price for an apple. So, highly differentiated products are marketable around the world, and the cost of transporting them to respective markets can be absorbed to a large extent. This, however, is subject to the prerequisite that products are extremely differentiated.

Therefore, one of the propositions of spatial economics is that a sufficient decline in transportation costs leads to the formation of large-scale agglomerations. Then, where in the world can we see an agglomeration of economic activities? Let's focus on East Asia, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) area, and the EU15. Back in 1980, these three regions together accounted for 70% of world GDP: 29% held by EU15, 27% by NAFTA, and 14% by East Asia. In the subsequent 20 years, the information and communication technology (ICT) revolution occurred, which led to a significant decline in transportation costs. As a result, although EU15's share in the world GDP became somewhat smaller, the share increased for NAFTA, and that of East Asia nearly doubled, whereby all three regions combined to increase to 83%, indicating that economic activities continued to agglomerate in these three major areas of agglomeration. Over the same 20-year period, world GDP grew at an annual average rate of 3%, a level that is historically extremely high, and exports grew 5.7%. From 2000 onward, world GDP has been growing at an average annual rate of 6.4%. This is obviously inflated, and I would call it "normal" if we can maintain annual growth of 3% going forward.

The current high level of growth is attributable to the formation of two enormous agglomerations, namely, East Asia and the United States. Although Europe has always been home to large-scale agglomeration, agglomeration in Europe is primarily self-supporting in nature. In terms of the impact on global economic growth, the development of East Asia as the world's manufacturing center and the United States as the ultimate market for financial settlement and the world's largest asset market have been far greater factors. East Asia earns money by manufacturing goods as the factory for the world. In the years running up to the global financial crisis, much of the money earned in East Asia was not spent there but instead was channeled to the United States, typically in the form of investments in the U.S. asset market. This is how the enormous asset bubble was developed there, which in turn caused an unsustainable global imbalance and brought us to where we are today.

Economic growth in East Asia and the development of a regional economic system

Looking back on the process in which East Asia evolved into the manufacturing hub of the world, we can see that East Asian economies followed the flying geese pattern of development up until the early 1990s. This gradually developed into de-facto integration, whereby these economies formed a multicore network economic system and together developed into the manufacturing hub of the world. For instance, labor intensive industries such as textiles, which used to have a large presence in Japan in the 1950s and 1960s, shifted to nearby economies such as South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore in the early stage of the flying geese pattern of development, and to ASEAN countries in the later stage. Then, in the 1990s, China and India joined in as new hubs for intensive industries and, with this, the flying formation shifted from the geese pattern to one that looks more like a horizontal row. As a general process, when transportation costs are lowered, activities based on established technologies disperse in search of lower costs. However, such dispersion does not occur in an evenly distributed manner. Instead, as activities disperse from a certain location, a new cluster emerges elsewhere. By the way, this does not mean that Japan, which used to be the lead goose and a major hub for manufacturing activities, will be emptied out as knowledge-creation activities continue to concentrate in specific large cities because of the significant dynamics of knowledge externalities as agglomeration forces. In any case, since the 1990s, Asian economies have undergone remarkable development through the formation of an extensive multi-core network linking major cities and industrial clusters, and Asia as a whole has become a virtually integrated economic zone underpinned by mutually complementary relationships. This is what former RIETI President Masahiko Aoki referred to as "Flying Geese Version 2.0" in his lecture in the second round of this seminar.

Being the factory for the world, East Asia has a high concentration of manufacturing industries. Figures for 2008 show that East Asia accounted for 38.9% of the world's automobile production (of which Japan and China comprised 16.4% and 13.3%, respectively), exceeding by far the NAFTA and the EU. East Asia produced 67% of chemical fiber (of which 60% by China), 71% of mobile phone (51% by China and 12.3% by India), 96% of digital video disk (DVD) recorders/players (71% by China). Excluding designing and research and development (R&D), the production of personal computers (PCs) is almost entirely undertaken in East Asia. In 2008, the region accounted for 99.8% of the global production and China alone comprised 96%. East Asia held 100% share of the global production of hard disk drives (HDDs). However, unlike the case of PCs, the production of HDDs is not monopolized by China. In 2008, Thailand had a far greater share than China, while Malaysia and Singapore accounted for more than 20% each. East Asia also hold 100% share in digital cameras, in which Japan is putting up a fairly good fight. All these figures show that Asia--and China in particular--has surely grown into the factory for the world.

However, while Asia as a whole continues to grow driven by the economies of agglomeration, disparities are widening across countries within the region. For instance, comparison in terms of GDP per capita shows that the level of Singapore, the top country within the region, is more than 100 times that of Myanmar. Such a situation is sustainable. So, it is necessary for Asia to pursue the so-called "inclusive growth" through bottom-up cooperation.

When we look at China, one prominent feature is its population numbering 1.3 billion. This means that a country with a population 10 times that of Japan, which itself is the fifth most populated country, is just over there. For instance, Shanghai's population is about 20 million, and the combined population of Shanghai and its two neighboring provinces--Zhejiang in the south and Jiangsu in the north--is comparable to that of Japan at about 130 million. Having a population 10 times larger, China is huge as a source of labor. Furthermore, as wages have been on the rise, China has also grown into an enormous market.

Another characteristic of China is that the urban population ratio remains around 50%, meaning that there exists huge potential for development. The productivity growth of an economy is driven by agglomeration at least in the initial stage and then proceeds with urbanization in the later stage, whereby the core of agglomeration shifts from agriculture to manufacturing and then to services. As such, I believe that in 20 years or so, China's urban population ratio will be approaching 75%.

China has achieved rapid development since the mid-1990s. In the process, however, young people were driven out of rural areas, creating massive disparities between urban and rural China. Economic growth, agglomeration, and disparities occur simultaneously, at least in the initial stage of rapid development. Indeed, Shanghai's GDP per capita was 10 times that of Guizhou Province in 2006. China is making nationwide efforts toward narrowing such vast disparities. One such effort is a plan to build a transportation network extending to inland areas. Nearly 45 years have passed since Japan's first shinkansen began service between Tokyo and Osaka in time for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. Today, the shinkansen serves approximately 2,000 km from Aomori to Kagoshima. In China, high-speed trains operate only in two areas, respectively in and around Beijing and Shanghai, with a total distance of less than 1,000 km at the moment. However, a 1,400 km line linking Beijing and Shanghai will be put in service in June this year. China had earlier planned to complete a high-speed railway network with a total distance of 20,000 km by 2020, but the schedule has been moved up and the high-speed railway network is expected to stretch beyond 20,000 km. Although it is hard to find a place to sit down within the shinkansen waiting areas at Tokyo Station, you will see a number of chairs in a very spacious waiting room at Beijing Station, which looks more like an airport waiting room. China initially planned to purchase shinkansen trains of the same model as Yamabiko. However, this plan was later dropped as China wanted to achieve a top speed of 350 km per hour, whereas the Yamabiko can only attain 290 km per hour. Thus, China imported high-speed trains from Siemens of Germany, and Chinese manufacturers have reproduced them. This means that China has the technological capabilities to do so. Passengers are served tea while travelling, and trains quickly reach speeds of 330 km per hour even in a short distance of 150 km between Beijing and Tianjin.

This is a typical case of leapfrog development. As referred to in development economics, leapfrog development occurs when a developing country leaps over advanced countries by boldly introducing leading edge technologies. Japan leapfrogged in the postwar high growth period. Going forward, China may be leapfrogged by other countries from behind. Through and with such dynamic changes, the world will continue to develop.

Rebuilding the world and the East Asian economy toward a more balanced development

East Asia, taken as a whole, has already overtaken the United States and has vastly surpassed the eurozone in GDP. Needless to say, it owes much to China. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) also forecasts rapid growth for China in the years to come. It is thus expected that East Asia, as a whole, will eventually comprise a significant proportion of the world GDP and grow into the largest market in the world.

However, these are nothing more than predictions and not guaranteed. In order to turn these predictions into reality, it is necessary to change drastically or rebuild the economic structure of East Asia and that of the world into a more balanced one. Globalization or borderlessness is the key to rebuilding the economy, and it is quite natural to focus on the manufacturing sector. At the same time, we must remember that the world is now evolving into what I call a "brain-power society" or a society in which knowledge-creation activity plays a central role. For instance, central activity in Tokyo is not narrowly defined manufacturing but broadly defined knowledge creation that includes the gal industry and service industries. What is important is to strike and maintain a reasonable balance between the two. That is, in considering the future of East Asia, which is currently serving as the world's manufacturing base, it is necessary to build a new institutional system and achieve a knowledge renaissance. For this, we must create a brain-power network in addition to effective production and transportation networks. Through such a process, East Asia can evolve into a more advanced and innovative manufacturing base for the world, while at the same time becoming a major global market and serving as a world-class base for creative activity. Only then will East Asia be able to become the third pillar of the world, following Europe and the United States, to pave the way for more balanced global growth.

With a clear intention to transform East Asia into such a creativity hub, various innovation activities are being undertaken in countries across the region. In R&D investment as a percentage of GDP, Japan has been maintaining the top position among developed countries since 1985. This is quite important. Although Japan seems to have lost much of its confidence, in the eyes of other Asian countries, Japan possesses enormous technological power, and massive R&D investment is the source of that power. However, most of Japan's R&D investment comes from the private sector, and R&D investment by the government sector remains extremely low at 0.75% of GDP. The need to increase government R&D expenditures has been pointed out, although only to 1%.

In the meantime, South Korea is rapidly catching up and might have reached a level comparable to Japan in 2010. China's R&D investment has been on a sharp rise as well. Including military-related R&D investment, which is not reflected in the figures I have just mentioned, China's R&D investment in terms of percentage of GDP is probably as high as those of the United States and Japan.

Meanwhile, in terms of the number of patents published by research area, China ranked at the top in the environmental area, exceeding the United States and Japan. In the area of biological sciences, the United States has the largest number of patents published, and Japan is roughly on par with Europe. However, China is approaching the level of Japan and Europe, with South Korea fast approaching.

So, active R&D efforts are being made in countries and regions in East Asia, and broadly defined knowledge renaissance is already beginning to take place. However, the knowledge network within East Asia remains extremely weak and far from being comparable to those observed in Europe and the United States.

When requesting the granting of a patent for an invention, the applicant must cite all prior patents related to it. World Bank data show that although a fairly large number of patents registered in Japan are cited in patent applications filed in East Asia, those registered in the United States are, by far, the most cited, and only a very small number of patents registered in other Asian countries, i.e., excluding Japan, are cited in patent applications filed in the region. This means that the United States is playing a dominant role as a knowledge hub in the world at the moment. However, so far as the electronics area is concerned, Asian patents are more cited than those of the United States in patent applications filed in Asia, indicating that the Asian knowledge network is taking shape in specific areas. Creating a brain-power network is the key to turning Asia as a whole into the third global hub for creative activities following the United States and Europe. Through this process, we will be able to mobilize diverse brain powers from all across Asia to bring about a knowledge renaissance.

Diversity and culture in a knowledge-creation society

In order to transfer the entire Asia region or all of Japan into a knowledge-creation society, we must develop more comprehensive theories of spatial economics. The theory of new economic geography, which emerged in the 1990s, focuses on economic linkages (E-linkages), i.e., linkages through the production and transaction of traditional goods and services. Here, the production of ordinary goods is surely important, but the importance of knowledge linkages (K-linkage), i.e., linkages through the creation and transfer of broadly defined knowledge (including ideas and information) is becoming critically important today. In order to make spatial economics more comprehensive, the theory explaining the working of these linkages must be reinforced and it would be necessary to conduct more empirical research.

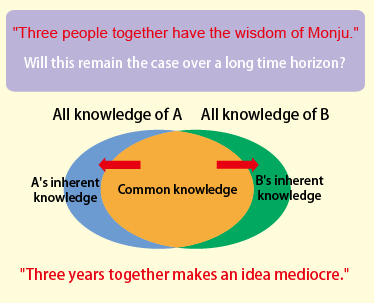

Spatial economics considers diversity as the source of agglomeration and productivity growth. In a knowledge-creation society, the most important resource is our brain. Just like there is no point in having many copies of the same computer software, having many brains of the same kind would not create any synergy. Only by bringing together diverse brain powers--a group of people with each having differentiated knowledge--will it be possible to create synergies. In Japan, we have an old saying, "san-nin yoreba Monju no chie", which literally translates as "three people together have the wisdom of Monju (the saint of wisdom in Buddhism)." This holds true for the case of two people. Of course, a degree of common knowledge is necessary as a basis for communication and cooperation. However, if all knowledge is common, there is no point in cooperating. Therefore, an adequately balanced mix of inherent and common knowledge is crucial to creating synergies.

So, the proverb "three people together have the wisdom of Monju" is quite important. But will this remain the case over a long time horizon? When the same three researchers continue to work and write papers together for too long, their common knowledge will increase and inherent knowledge will decrease in proportion, resulting in the phasing out of synergies. This kind of phenomena is actually happening in Japanese companies and research organizations. Having the same members engaging in research over a prolonged period of time would turn what used to be "san-nin yoreba Monju no chie" into "san-nen yoreba tada no chie" (three years together makes an idea mediocre). Thus, we must remember that the centralization of knowledge workers is double-edged.

Tokyo has been the knowledge center of Japan ever since the Meiji Restoration in 1868, drawing a predominant proportion of knowledge workers from diverse backgrounds. The concentration of knowledge workers and their close communication created and increased synergies and served as a major source of Japan's growth over a short period of time. However, by sometime in the 1980s, Tokyo had absorbed all of those who were to be absorbed. Furthermore, the revolutionary development of ICTs prompted media organizations--TVs and newspapers--to centralize their operations, whereby Tokyo virtually became the sole source of nationwide news and programs. If everyone watches the same TV programs and reads the same newspapers, they will eventually be filled with predominantly common knowledge, producing a population with identical ideas and knowledge and eliminating synergies. In order to prevent this from happening, it is necessary to develop intentionally diverse organizations and regions and promote knowledge exchanges and human mobility.

One reason behind Japan's lack of vitality is its weakness in overall innovation capabilities relative to the United States. In this regard, an extensive questionnaire survey of Japanese and U.S. inventors, conducted by RIETI Faculty Fellow Sadao Nagaoka, who is also a professor at Hitotsubashi University, offers some interesting insights. The survey, conducted with over 3,000 inventors (granted for cutting-edge inventions) in Japan and the same number of those in the United States, found that one of the most distinctive differences between the two countries is the very high mobility of U.S. inventors. More specifically, 25.7% of U.S. inventors--45% in the area of biotechnology--moved to another company, university, or elsewhere in the past five years, whereas only 4.6% of Japanese inventors did so. Also, foreign-born inventors account for 30% of U.S. inventors, compared to almost zero in Japan. In the U.S., frontier-type research, which accounts for a large segment of overall research activities, have led to many unintended, surprising results, whereas most research efforts in Japan produced intended results. Furthermore, those with doctoral degrees account for 45% of inventors in the U.S. compared to only 12% in Japan. This indicates that Japanese researchers are mostly trained within their respective companies. The practice of in-house training might have worked well until now. However, we must do something about the current low mobility of researchers.

Japan must break away from the lock-in effect of the existing homogeneity-based, improvement-seeking innovation system and shift to a new knowledge-creation system focusing on a heterogeneity-based, discovery-seeking innovation system. For that, it is necessary to strengthen cross-organizational cooperation to facilitate the gradual shuffling of members and absorb new talents. It is also necessary to overcome the problem of over-centralization and reinforce the culture of more diverse regions.

Now I would like to explain the relationship between this culture (agglomeration of unique knowledge) and creativity by assuming a pair of contrasting regions. Suppose an economy has two symmetric regions--instead of a highly centralized, unipolar structure--with each region having an agglomeration of knowledge unique to itself. Within each region, close interaction takes place. So, two typical individuals taken from the same region have much knowledge in common. In comparison, in the case of two typical individuals from two different regions, the amount of common knowledge between them is much smaller as inter-regional communication has costs. This difference in knowledge between the two is what we call culture here. Improvement-seeking research can continue to take place under close communication within each region. However, in knowledge frontier-type research such as in the area of biotechnology, diversity is crucially important, and a team of talents brought together from the two regions can significantly enhance R&D capabilities. Regarding this, I have written in detail in the discussion paper, Culture and Diversity in Knowledge Creation, soon to be published on the RIETI website.

Now, let me assume two cases. In the first case, research is conducted in only one of the two regions, and collaboration and communication between the two regions can be made at no costs. In the second case, the task of research is divided between the two regions, and collaboration and knowledge transfer between the two regions involve costs but result in greater diversity. By comparing these two cases, we have found that growth in region-wide knowledge in the second case can be nearly three times that of the first. This finding also points to the importance of knowledge diversity.

Rebuilding Japan in the era of globalization and knowledge economy

In Japan, we hear lots of talk about the "lost two decades." However, in the light of history, 20 years of stagnation is not such a big event. China had gone through 200 years of stagnation, and Greece has yet to emerge from its 2,000 years of stagnation.

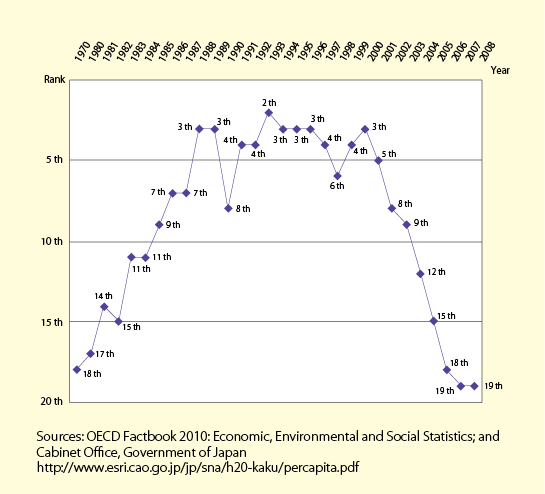

In the early phase of the postwar period, Japan achieved remarkable economic growth, sparked by the outbreak of the Korean War. Then, helped by the remaining momentum, Japan managed to ride over the Nixon Shock and the oil shocks. Having its economic structure based on the high-tech industries, Japan grew into the world's economic powerhouse--such that it was referred to as "Japan as Number One"--by the late 1980s. However, then came the burst of the economic bubble and ever since the 1990s, the Japanese economy has been stuck in mire just like a snowball trapped at the bottom of a ravine. Under the so-called mass production-oriented capitalist economy, importing and improving cutting edge technologies from the United States and Europe was all that was necessary, and Japan, just like today's China, leapfrogged into the world's top economy position in 1993 in terms of per capita GDP. Having reached that point, Japan must explore frontiers on its own and turn into a true brain-power society. However, due to the negative lock-in effect, it has been unable to change completely its structure. Japan, which was ranked 18th among the member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in 1970, climbed to second place in 1993, or first place depending on the exchange rate applied for statistical purposes. After that, however, Japan dropped sharply in the ranking to 19th in 2008. This cannot be explained by changes in the foreign exchange rates alone. There must have been major structural factors.

In 2008, Luxembourg topped the list with per capita GDP three times higher than that of Japan. The top 10 countries for this year were Luxembourg, Norway, Switzerland, Denmark, Ireland, the Netherlands, Iceland, Sweden, Finland, and Austria. All of them are small European countries with a combined population of 63 million, roughly half that of Japan. Also, the distance from Helsinki, Finland to the Netherlands is shorter than the distance between Hokkaido and Okinawa. That is, a relatively small geographic area has a cluster of these small countries with diverse backgrounds. What is important here is that these countries, each of which is an independent state with its own language and culture, have successfully transformed themselves into a highly advanced knowledge society through their respective policies. This provides a good guidance for Japan's future.

In order for Japan to play once again an active role as one of the world's leaders, it must become a global hub for innovation and knowledge creation in a way that is distinctive from other countries. An important factor for this is the diversity and autonomy of everything. In all aspects ranging from people and human resources to businesses, universities, and cities and regions, Japan must restore and strengthen diversity and autonomy. In particular, the diversity of human resources and regions must be reinforced to meet the needs of the knowledge era.

I personally believe that competition and coexistence through an autonomous decentralized governing system will become the basis for future regional policies. The replacement of fairly autonomous feudal domains with centrally controlled prefectures, a sweeping governing system reform implemented as part of the Meiji Restoration, turned Japan into a highly centralized nation state with Tokyo at its center. This system worked well in the first 20 to 30 years. This does not necessarily mean that the system will continue to serve as an appropriate form of governing going forward. As an antithesis to the Meiji Restoration and centralization, I am proposing Heisei Restoration and decentralization, or a shift from the existing centralized governing system to a decentralized one by creating more diverse and autonomous regional centers.

The centralized governing system created by the replacement of feudal domains with prefectures has had its good and bad sides. As one of the good sides, we can cite the fact that the system as a whole functioned extremely well in catching up to industrialized nations such as the United States and European countries, which resembles how the Chinese Communist Party system works in today's settings. At the same time, however, Japan lost diversity and autonomy in many aspects of society. Compulsory education, which is based on the idea that acquiring knowledge is remembering the most advanced right knowledge of the time, and school entrance examinations, in which students are primarily tested for their memory skills, have deprived children of their individualities and creativity. The central control of local authorities deprived local regions of their autonomy, resulting in the bloating of common knowledge and turning the Japanese population into masses of people that are of the same sort in their ideas. This highly centralized system should be replaced by one based on smaller but diverse regional centers, each embracing industrial and knowledge clusters or knowledge and cultural agglomerations unique to itself, whereby these regions--through competition and coexistence--would together serve as a driver of nationwide knowledge renaissance and develop as an innovation center. Such is my proposal.

If this is to be realized, utilizing the existing regional resources to the fullest extent and bringing in new people and knowledge from the outside should be the basis for each region's policy. Through such a process each region can create its own unique environment, culture, and framework that would bring excitement to all people living in the region and pave the way for sustainable innovations. And it is the role of the central government to create a mechanism that facilitates the emergence of diverse regions.

One major challenge common to all regions is how to nurture diverse human resources or attract them from across Japan and the world. Simply waiting will not work. The diversity of people is to evolve with the capacity for embracing diversity and outsiders, and making it happen requires intentional efforts. Thus, the enormous challenge for these regions is how they can expand their capacity for broadly defined outsiders through proactive and concrete policy measures. "Outsiders" here refers to those left outside of mainstream society. We should let them join the mainstream and play an active role, particularly, as core members of a knowledge-creation society.

Typical examples of outsiders include foreign nationals living in Japan. Although foreign nationals are welcomed and treated kindly so long as they are here as guests or visitors, they face a range of difficulties as residents. Indeed, it is difficult to become a public servant or faculty member at university, and some foreign workers are unfairly treated. Young people who have dropped out of school as well as those who are overeducated, such as PhD degree earners, often find it difficult to get a job whether at a company or at a government agency. Other outsiders include middle-aged and elderly people who wish to play an active role in society, as well as people with handicaps. However, one area in which Japan is particularly poorly compared with other developed countries is in the treatment of women. For instance, only two of the 99 national universities in Japan have a female president, compared to four--including Harvard University and the University of Pennsylvania--out of the eight Ivy League universities in the U.S. Indeed, in the U.S. as well as in northern Europe, there is no gender gap in knowledge-creation activity, and no one is blocked from playing an active role in the mainstream.

Conversely, we could say that Japan has tremendous potential to grow by letting foreign nationals and women play more of a role in the mainstream of society. At the moment, foreign nationals account for less than 1% of skilled workers in Japan, compared to 6% in the U.S. and North Europe. In order to make major progress in terms of utilization of human resources and human diversity, Japan must implement the aforementioned measures with a clear intention to achieve that end.

Among Asian economies, Singapore is most effective in taking advantage of the diversity of human resources. Singapore, which is the No. 1 country in Asia in per capita GDP, has been making strenuous efforts to enhance its acceptance of outsiders and promote internationalization. Let me introduce an interesting article I found in the Far Eastern Economic Review, a business magazine that ceased publication a couple of years ago. The article, titled "Gay Asia: Tolerance Pays," is about an annual gay party, which was held on the national day of Singapore in the midst of summer bringing together some 8,000 gays from all over the world. With barely clad participants dancing all night, the event is wild by any standard and would have been unthinkable 10 years ago. Back then, Singapore was highly centralized and known for its extremely stringent regulations. People often said that one could get arrested for possessing chewing gum in Singapore, even before having a chance to chew it, as a police officer would say, "You have chewing gum. You are going to chew it. And when you finish chewing, you will spit it on the road. So you are arrested." Singapore has now become very open with the government making intentional efforts to accept outsiders and enhance broadly defined tolerance for things different. This means that each region in Japan can emulate Singapore to promote internationalization and revitalize local economies and activities.

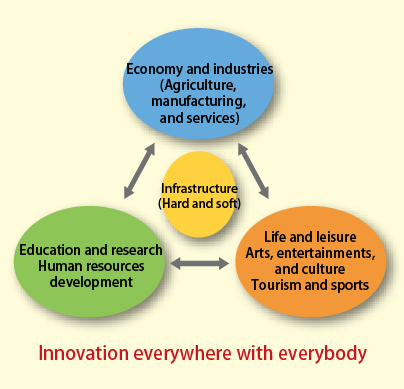

Regional revitalization by all people through diverse approaches

Revitalization efforts must be undertaken by all people in all areas through diverse approaches. Needless to say, we must further promote education, research, and human resources development to turn Japan into a more robust science and technology powerhouse. At the same time, we must vigorously promote cutting-edge R&D in the manufacturing sector, and there remains significant room for development in the agricultural and service sectors. This involves efforts both in hard and soft aspects. In addition, the arts, entertainment, and culture are what make the world enjoyable. It is important to ensure that all those areas are distinct from one another but, as a whole, compose a unity, just like the three gods in the Trinity. I think we should pursue "innovation everywhere with everybody," which would include not only Tokyo but also the regional areas.

What we must keep in mind here is that there is a tendency to emphasize equality in Japan. For instance, there is a strong sentiment that we should protect elderly people, small and medium-sized enterprises, women, local areas, agriculture, and so forth. We must change this perception and create a new system in which all people play a major role in bringing about social innovations. It will be impossible for a small number of young people to bear all of the burden. Although both South Korea and China will, sooner or later, face rapid population aging, Japan is moving ahead of them. In order to realize a new form of aging society, Japan must pursue new business innovations and thereby build a new business model or social system whereby everyone can be a major player.

In fact, such new innovations are occurring in various parts of Japan. The revolutionary development of the gal industry in Tokyo is a fashion revolution revolving around young women. Meanwhile, in rural areas, elderly farmers--particularly elderly women--are bringing about a rural revolution.

For instance, Kamikatsu in Tokushima Prefecture is known as a "town that has turned leaves into money." The town, located in a mountainous area about a two-hour trip from the city of Tokushima and having a population of only about 2,000, has been the scene for many interesting activities. The Irodori project is one of them. It is a business to sell cherry branches and maple leaves as garnishes for dishes served in luxurious ryotei Japanese restaurants. Local farmers produce some 400 kinds of garnishes for each season and ship them to restaurants in 90 cities across the country. It all started with unusually heavy snows in the winter of 1980, which totally damaged orange trees and deprived local farmers of their main source of income. Those farmers also grow rice, but production volume is extremely limited as there is not much they can do in the bottom of valleys. Cash income per farming household for that year and thereafter was only about 200,000 yen. After agonizing over how to find their way out of the hopeless situation, Mr. Tomoji Yokoishi and four housewives launched the project in 1986. Selling leaves as garnishes for dishes is something anyone can do. Yet, it was a big innovation because no one had done it before.

When Mr. Yokoishi, the mastermind of the project, hit upon and proposed the idea, he received two typical responses. One response was, "If simply collecting leaves makes money, Japan should have been full of rich people from Hokkaido to Okinawa. This cannot be true," while the other was, "Making money by selling leaves is unbearable. It is so shameful." Despite such negative responses, Mr. Yokoichi was confident and persuaded them. Today, approximately 150 farmers--the majority of them elderly women--are engaged in this business. With the oldest member aged 95 and the average age at 67, they earn 1.7 million yen per person per year. The amount may look small, but many of them are married couples and in most cases both the husband and wife participate, bringing the household income to 3.4 million yen, roughly 15 times the average income per farming household in Kamikatsu prior to the launch of the project.

This project is now packed with know-how accumulated over the past 20 years and makes full use of information and communication technologies. They grow seedlings in their own fields, collect leaves, and ship them out on their own. So, each one of them is the business owner cum worker. Even though they are directly linked to the market, they need to analyze market movements to determine their shipment volumes, for instance, how many cherry branches they should ship tomorrow. Specifically, they need to obtain necessary data--price data for 90 cities over the past one month period and price forecasts for the coming one month--from respective municipal governments and analyze them on computers. The Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry helped in the development of the computer network for the Irodori project, including the development of an elderly-friendly mouse the size of a tennis ball. Following the introduction of a computer network, overall sales for the Irodori project more than doubled. Based on the information they obtain via computers, Kamikatsu farmers decide their shipment volumes, pack the products, and bring them to the local agricultural cooperative by 4 p.m.The products are then transported to the Tokushima Airport and, from there, sent out to 90 cities across Japan. They are joining forces to develop new products.

Today, Kamikatsu has come to be known as a "town of smiles." It is surely nice that people can earn a reasonable amount of cash income while living in nature. What is more important, however, is that they have entered the mainstream of society by establishing a direct link with the market and yet continue to live in the town that lies in a beautiful natural environment. Of the town's population of 2,092, 6.3% are newcomers or returnees from cities. There are many others wishing to come and live in Kamikatsu, but there seems to be a limit in terms of land available for them. Among the municipalities in Tokushima Prefecture, Kamikatsu has the highest proportion of aged citizens. Despite this, the town has not a single person bedridden at the moment, and the annual medical spending per person amounts to only 260,000 yen per person, compared to 460,000 yen in the municipality that ranks second in the proportion of elderly population and has no special activities comparable to those of the Irodori project.

Indeed, the Irodori project is not the only project undertaken in Kamikatsu. For instance, the mayor of Kamikatsu invites people to compete in new ideas in a program dubbed as Ikkyu Undo held approximately once a month. The unique part of this program is that offering new ideas is not the end but the beginning of this practice. Those who offered new ideas are required to report three months later on how they have materialized these ideas, whereby other members will be asked to offer advice for further improvements. As such, Kamikatsu is a town where people live with smiles on their faces, earn reasonable cash income, and spend little on medical care services. In the same way, we can create new business models in and for cities and towns across Japan, and it would be nice if we could invite China and South Korea to join us in this endeavor. What is important is to make this movement into "innovation everywhere with everybody."

Toward a creativity-driven country that is open and has rich diversity

Japan, which still remains a highly centralized country, is depressed and dispirited. One way to break free from this situation is to transcend national borders. Prime Minister Naoto Kan also calls for opening up the country. Japan must integrate itself with the rest of Asia and the world in a sustainable manner. The presence of diverse human resources and regions is crucial to maintaining Japan's agglomeration forces. By abolishing the centralized governing system and creating diverse regional areas, we must transform Japan into an innovation center where everyone is a major player and make it an integral part of the world. In this way, Japan should become a creativity-driven country that is open and has rich diversity. Such is my idea.

*This summary was compiled by RIETI Editorial staff.