Under the Strategic Priorities July 2023 - June 2024, announced in August 2023, the Financial Services Agency (FSA) is advancing the concept of turning Japan into what it refers to as a “leading asset management center” and promoting the “Doubling Asset-based Income Plan.” Naturally, there are expectations that the effort to implement the plan will ensure that asset building by the people leads to financial stability in old age. Several years ago, controversy erupted over an estimate that a married couple needs to build up savings worth at least 20 million yen if they wish to lead a comfortable post-retirement life. According to the most recent data, the estimated savings threshold for a comfortable old age is around 9.3 million yen. With the large discrepancy between these figures, it is difficult for the public to project the amount of savings that needs to be set aside by the time of retirement. Japan is ranked 56th among the 149 countries in the World Happiness Index, which represents a low standing among developed countries, and the greatest day-to-day economic concern of the Japanese people is post-retirement planning or post-retirement life design (Note 1). This article examines the issues that need to be addressed to turn Japan into a leading nation in terms of asset management, focusing particularly on the pension system, which serves as a vehicle for resolving economic anxiety over post-retirement life.

Rating the Japanese pension system

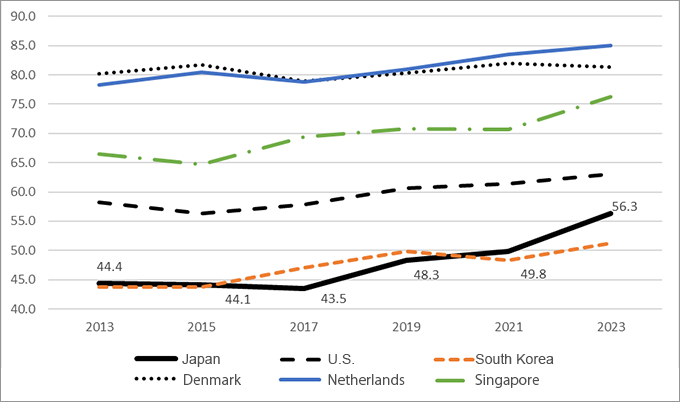

According to the Global Pension Index 2023, announced in October by Mercer, a U.S. consulting firm, the Japanese pension system was given a score of 56.3, 30th among the 48 rated countries. Simple international comparison of pension systems is difficult because each system reflects that country’s history and customs and also because other domestic systems and practices, such as retirement benefits, must also be taken into account. In Japan’s case, if governmental support under the public welfare and health insurance systems provided to people with low pensions and elderly people are taken into consideration, it is assumed that the actual living standard of people in old age are higher than the level suggested by the pension index score. Over time, the rating of the Japanese pension system has improved significantly (Figure 1), reflecting the effects of the legal amendment made to promote defined-contribution pension plans and the expansion of coverage of employee pension plans. In addition, the “macroeconomic slide” mechanism, which automatically adjusts the level of pension benefits in accordance with macroeconomic conditions, is held in high regard as a mechanism for stabilizing pension finance.

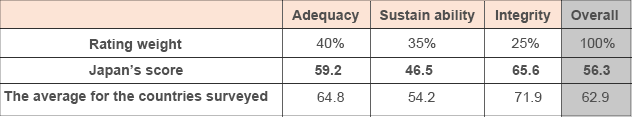

However, there are still unresolved problems related to the Japanese pension system itself. Aside from the adequacy of pension benefits or the sustainability of the pension system, each of which is strongly affected by structural factors, such as the deterioration of the government’s fiscal position and the demographic crisis (the aging of society coupled with a chronically low birth rate), there is ample room for the government to improve the integrity of system management in particular, which mainly concerns the governance and system administration of private pensions (Table 1).

Trends and problems related to corporate pensions

The total outstanding balance of pension reserves in Japan is 492 trillion yen (as of the end of FY2021), of which public pensions account for 271 trillion yen, or 55%. Corporate pensions account for around 88 trillion yen, or 18%, with reserves under defined-benefits (DB) pension plans and reserves under defined-contribution (DC) plans making up 14% and 4% of the total, respectively (Note 2). Given that a future decline in benefits paid by the public pension system is inevitable, there are expectations for private pensions—of which corporate pensions are the representative type—to play a complementary role.

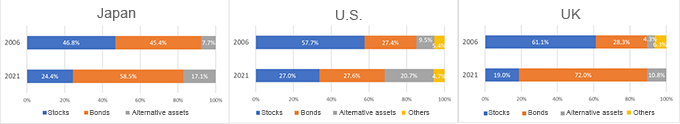

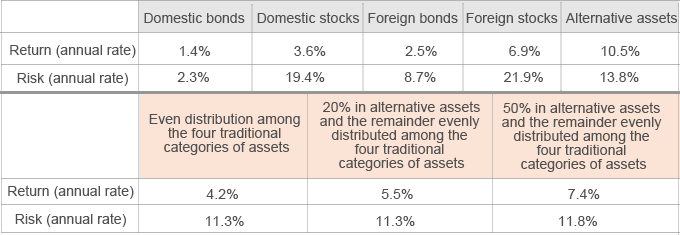

Under the government’s policy for turning Japan into a leading asset management center, corporate disclosure of their investment situation will be promoted in order to encourage corporate pension funds to raise their prospective yields. However, the management of corporate pension assets is largely a function of decision-making regarding the policy asset mix. A look at changes in the asset mix of corporate pension funds in various countries over the past 15 years shows that fund managers have engaged in the rational behavior of trying to maintain returns while reducing risks by shifting the asset mix away from stocks to (1) bonds—as a way to reduce risks—and (2) alternative assets—as a way to secure returns (Figures 2and Table 2). Moreover, compared with cases where the asset mix is comprised entirely of the four traditional categories of assets (Figure 4), it is estimated that allocating 20% of the mix to alternative assets will deliver a higher return while the risk level remains similar, and in the case of corporate pensions in Japan and the United States, the actual share of alternative assets in the asset mix is around 20%. It seems that Japanese corporate pensions are not inferior in asset management expertise to their foreign counterparts; rather, they are engaged in the reasonable behavior of trying to secure decent returns while controlling risks.

[Click to enlarge]

Corporate pension funds, unlike fiduciary institutions that earn fees in proportion to the amount of assets entrusted by clients, not only bear full responsibility for investment risk but also take various factors into account when deciding prospective yields and investment policies, including the management situation and personnel strategy of the companies whose assets they handle. Meanwhile, as the calculation of pension liabilities is based on the yield on the 30-year government bond, a possible future decline in bond prices due to an interest rate rise is, in a sense, hedged against, with the risk from holding bonds reduced. The asset mix and prospective yield are decided with due consideration given to a comprehensive set of factors, including the abovementioned ones, so simple comparison across different pension funds based on disclosure information is difficult. Meanwhile, there is a lack of clarity over the benefits that can be received in the future, which is the greatest matter of interest for pension plan members. Therefore, it is necessary for corporate pension funds to communicate more closely with pension plan members, for example by disclosing the estimated benefits that will be received, among other measures.

An integrated premium management system will start in December 2024. Under the system, for people who are members of both DB and DC plans, the contribution that can be made under the DC plan changes depending on the assumed premium paid under the DB plan, with the total allowable premium amount capped at 55,000 yen per month. This is intended to ensure equitability in total tax advantages received by pension plan members. However, in the past, many companies introduced a DB pension plan in place of lump-sum retirement allowances, and in that case, the contributions that can be made by employees under DC plans will shrink under the new system, which would mean inequality in another form. Moreover, of the DC plan members who are given the choice of receiving a lump-sum payment at retirement or a pension, more than 70% choose the lump-sum payment (Note 3). If the reason for that decision is the superficial perception that receiving lump-sum payments is more advantageous for pension plan members in terms of taxation than receiving pensions, factors contributing to that perception should be resolved. One option worth considering is balancing out the tax burdens between lump-sum payments and annuity-based pensions by increasing the tax deduction for pension income and decreasing the deduction for one-time income received in the form of retirement allowances. On the other hand, if employees are choosing lump-sum payments merely based on their understanding of the differences in tax treatment, they may be neglecting the characteristics of annuities. Given that the investment approach adopted under DC plans is passive—around 30% of DC pension assets are invested in deposits and other financial instruments that guarantee principal repayment—it is also necessary to consider the future of the pension system from the perspective of financial literacy.

Looking Forward (Conclusion)

As described above, Japan's pension system has faced major challenges, such as the deterioration of the government’s fiscal position and the demographic crisis, and while some improvements have been made, further study is necessary on what form the Japanese pension system should take in the future.

Therefore, I look forward to institutional reforms, including the reform of the DB-DC integrated premium management system and the taxation on retirement allowances. Although corporate pension funds have engaged in fairly rational asset management under some constraints, it cannot be denied that their information disclosure lacks specifics. Moreover, in some respects, there is a lack of financial literacy on the part of employees. Due to these circumstances, there is an initiative led by the Financial Services Agency to develop an integrated approach to the promotion of financial and economic education, which has been repeatedly attempted to no avail in the past, based on a plan to create a Financial and Economic Education Promotion Agency.

It is possible that increasing awareness and knowledge of individuals by promoting financial and economic education will lead to more proactive information disclosure by corporate funds, creating a multiplier effect in the form of a further improvement in financial literacy. Encouraging individuals to think about the pension system from their individual perspectives may indirectly lead to appropriate pension system reforms. I hope that through that process, the government’s initiative to turn Japan into a leading asset management center will relieve the people’s anxiety regarding retirement and lead to a higher level of happiness.

December 22, 2023

>> Original text in Japanese