Stalled industrial output in developed nations

Donald Trump's victory in the U.S. presidential election is building up high expectations for his economic policies. President-elect Trump pledged to reduce the federal corporate tax rate from the current 35% to 15% and make massive infrastructure investments worth $1 trillion over 10 years. He also mentioned lowering the top rate of the progressive income tax rates. The implementation of these policies would substantially expand the economy of the world's largest economic superpower. That would naturally have a positive impact on the world economy through the expansion of international trading activities.

However, we cannot be entirely optimistic. Trump's policies of trade protectionism and immigration control might temporarily protect domestic employment, but would reduce the supply of goods and labor. It is conceivable that the domestic labor market will be partially tighter, and the resulting wage increase will suppress corporate performance. Employment improvement has already applied an upward pressure on wages in the United States. If Trump enforces his pledge of deporting the two million illegal immigrants with criminal records out of the total of 10 million illegal immigrants, and assuming that they include one million in the workforce, the tight labor market situation will likely push up the wage growth rate by about 2% from the current 2.9% year-on-year (December 2016).

It is true that people in other developed nations are becoming more intolerant of the continued inflow of goods and immigrants from emerging and developing economies. In fact, global trade has increased by 11.2 times (source: International Monetary Fund (IMF)) from 1980 to 2015, when the world gross domestic product (GDP) rose by 6.7 times (source: World Bank). Exports from emerging and developing economies have grown by a staggering 46 times (source: IMF). Yet, the value of exports has declined over the last two years due to a drop in the prices of crude oil and other resources. According to data for up to 2013, when the prices of crude oil and other resources hovered high, export values grew by as much as 12.6 times worldwide and 52.8 times among emerging and developing economies since 1980. This indicates that exports from emerging and developing economies to developed economies grew to such extent.

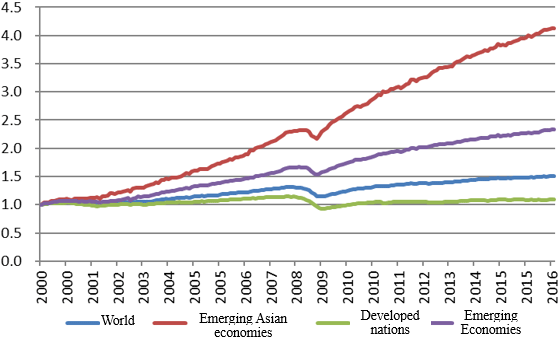

The impact of increased exports from emerging and developing economies to developed nations can be also seen from the changes in world industrial output. From 2000 to 2015, world industrial output increased by 1.5 times, while that of emerging economies rose by 2.3 times. Above all, growth in industrial output in emerging Asian economies including China, which has become the world's factory, reached 4.1 times (Figure 1).

Industrial output in developed nations, on the other hand, has remained largely steady, growing by just 1.1 times. It grew by 1.1 times in the United States and the Eurozone while remained even in Japan. Even consumers in industrialized nations may benefit from gaining access to cheaper industrial products from emerging economies, but they would not be completely satisfied if the imports hamper growth in domestic industrial output or employment and wages in the manufacturing sector. Just like after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, only public dissatisfaction would rise in developed nations if their economy and employment are not strong.

Innovation and differentiation are necessary

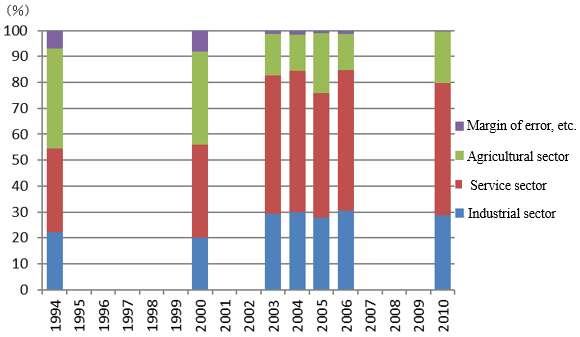

With the exports of emerging and developing economies growing faster than their GDP, the number of workers in the industrial sector is rapidly increasing in those countries, as opposed to the developed nations. Figure 2 shows the breakdown of the global workforce by sector since 1994. The ratio of workers in industrial sector increased from 22% in 1994 to 29% in 2010. As the global working population increased from 2.5 billion to 3.2 billion over this period, the number of workers in industrial sector workers increased by almost 400 million, from 550 million in 1994 to 920 million in 2010.

The increase in the global working population itself is a great thing as more people can earn a living. Increase in the working population in the industrial sector by almost 400 million within the past 20 some years has lead to an increase in production capacity, and thus, an increase in exports by emerging and developing economies. While increase in production capacity is essential when the world economy is growing steadily, it could negatively impact employment in developed nations, which are still suffering from the post-Lehman economic downturn, if a massive amount of competitive products produced with cheap labor flow in.

What is necessary for developed nations is not a policy package of demand increase and trade/immigration restriction, as claimed by Trump. Such policy might buoy the economies of these nations in the short term, but end up guiding them into a zero-sum game with emerging and developing economies and no positive impact on the world economy. A more desirable approach would be to increase the size of the world economy to create a win-win situation for developed, emerging, and developing nations.

A direction more suitable for developed nations leading the world economy would be to create innovative goods and services that generate new demand and promote innovation that facilitates such policy. For developed, emerging, and developing nations to gain a synergy through collaboration, they should not compete against each other in exporting similar types of goods, but it is important for developed nations to shift their weight to exporting intellectual properties and services while emerging and developing economies focus on exporting goods.

Needless to say, it would be difficult to achieve such innovation and differentiation in the short term. While developed nations are facing competition from emerging and developing economies in trade in goods, its service exports are steadily growing. Although it might take time, it is desirable that the world economy will expand to satisfy developed, emerging, and developing nations, and we need to watch closely to see if there are signs of such developments in 2017.