| Interviewee | FUJII Daisuke (Fellow, RIETI) |

|---|---|

| Issue date / NO. | Research Digest No.14 |

| Download / Links |

Modern societies are supported by complex production networks. The structures of production networks (inter-firm procurement, sales, etc.) have a variety of macroeconomic impacts. Much research has been done on the propagation effect of shocks in production networks, but so far there has not been much empirical research at the firm level. Using large-scale inter-firm transaction data, RIETI Fellow Daisuke Fujii examined the characteristics of transaction networks and their relationships to sales growth rates at firms and such rates at those firms' suppliers and customers (i.e., upstream and downstream firms), analyzing the extent of a shock propagation. This research has some effective implications for the building of a theoretical model of production networks, which could also aid in developing policies that help match firms with each other.

Background of the research

Q. Your area of specialty is international trade, so what spurred your interest in shock propagations in inter-firm networks?

Originally, trade theory concerned itself mainly with nation-to-nation trade, using macro data, and began with the Ricardian trade theory. Then in the 1980s, Paul Krugman and others started developing new models. The past 15 years have seen a great deal of research in the United States that incorporates the heterogeneity of firms into trade models, but these models were built on the assumption that every firm is independent and the empirical research has largely followed this trend. Therefore, the clear interactions between firms, especially inter-firm production networks through intermediate inputs, did not factor into the trade models, so I became interested in work that implied this.

I also read papers on propagations of shocks after the financial crisis, the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers, and the Great East Japan Earthquake. I found evidence of how shocks at individual firms could propagate to the entire economy in those papers. I therefore realized how important it is to demonstrate this by theoretically incorporating it into our models. This had not yet been done in the field of international trade, so it was my starting point. However, I also realized that I'd need to truly understand the mechanism through which a shock at an individual firm could propagate to the entire economy before incorporating it into trade theory.

Q. What has been found out already so far about the mechanism of shock propagation?

In 2010, Xavier Gabaix pointed out that in economies where there is some bias in the distribution of firm scale, the individual shocks of large firms can account for macro fluctuations. Then, a 2012 paper by Daron Acemoğlu et al. provided a microfoundation to the idea by considering inter-firm transaction networks. Namely, firms and industries that have many partners also have high sales, and that is why they can have such a big effect on macro fluctuations.

Although the Acemoğlu et al. model treats all connections to other firms as being reflected in sales and thus can be used to create an indicator of impact, it still describes a one-to-one relationship with sales. In other words, they were looking only at the scale of sales to explain the impact of individual firms on macro fluctuations and did not include an explicit network model.

But if we look beyond the differences caused by the distribution of large and small firms and expand our interest to the route by which shocks propagate, the network structure becomes very important. When it comes to macro fluctuations, economists largely understand that firms with many connections have a big impact, but it is critical that we really grasp the kinds of firms to which such firms are connected and the route and mechanism through which shocks propagate. This is important, for example, when governments are thinking about using public funds to rescue specific firms.

On the research content

Q. What was your perspective as you analyzed shock propagations in your recent paper?

I started with the premise that the paper would not go into the causal relationship, and just focused on the correlation between a firm's sales growth rate and its partners' sales growth rate. You wrote an excellent paper on shock propagations following the Great East Japan Earthquake, which delved into the causal relationship. My perspective was different, however. My starting point was to get an overall panoramic view by covering a large number of firms and sectors. I was trying to get a comprehensive understanding of how the size of the shock propagated varied based on factors such as firm characteristics.

Q. My own research tells me that shocks propagate out to indirect partners and that within the network structure, many firms are indirectly related. I understand that it is very important to consider indirect partners. What innovative ideas and analysis techniques did you use in your research?

When you try to measure the relationship between an individual firm's sales growth rate and that of its partners, there is the well-known problem that a network structural bias will assert itself when a simple regression analysis is done. To overcome this, I performed my analysis with a spatial autoregressive model, such as that which is used in spatial economics among others. This model basically measures the size of the propagated shock taking all network effects into account, so my analysis also accounted for indirect partner effects.

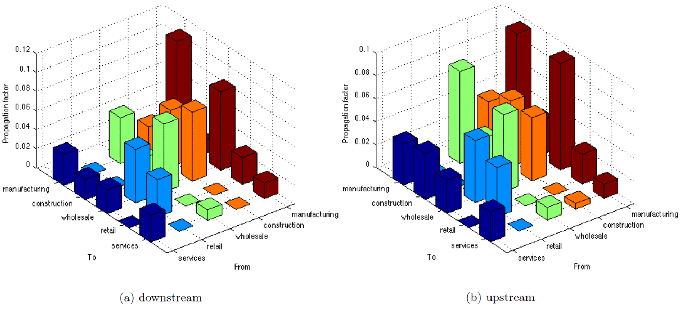

I also carefully sorted out the shocks based on whether they propagated to the firm's suppliers (upstream firms) or to its customers (downstream firms). Plus, an additional value of this research is that I was able to examine how the propagated shocks differed based on firm characteristics such as industry sector. I took several different approaches to examining how the propagation characteristics differed from each other. For example, I tried sorting the firms into manufacturing and non-manufacturing firms, breaking them down into five sectors (see Figure), sorting them out by size, and so on.

[Click to enlarge]

Lessons from analysis results

Q. What did you learn from the analysis results?

I learned that basically, in each year, there were bigger shocks to upstream partners than downstream partners. In other words, the upstream propagation factor is higher in all years. As I mentioned before, this analysis looked at correlations and not causal relationships, but one possibility is that it is more difficult to find alternatives when events occur on the customer side than when they occur on the supplier side.

By industry, the results show that in all years, there were much greater propagation effects for manufacturing firms than non-manufacturing firms. The same phenomenon was discussed in a paper by Javier Cravino and Andrei Levchenco in the forthcoming Quarterly Journal of Economics. That paper looked at the correlation between sales at parent companies and at their overseas subsidiaries. Here too, the results indicate a much higher correlation for manufacturing firms than service firms. There is a strong possibility that this occurs because manufacturing firms handle physical intermediate inputs that are difficult to substitute if something happens.

When I divided the firms into five sectors, again, the connections between manufacturing sectors had the highest propagation factor. Conversely, the results for retail and service sectors showed practically no propagation factor. This shows that retail and service sectors are not so dependent on their suppliers and customers.

Q. Did you find any differences between long-term and short-term shock propagation, or any difference by year and so on?

I was looking at yearly data, so essentially all of the shocks were short-term, but over the long term, I think shocks are absorbed and softened to some extent. I believe that there are probably differences in long-term and short-term propagation based on sectors.

Also, I was analyzing the years 2006, 2011, and 2012. Although there was some variability among the numbers with regard to the size of the shock propagated, the fact is that it would be hard for me to illustrate relationships with changes in business conditions since there are findings from only these three years of data. If I had 10 years of data, for example, I could correlate the findings with business cycles, so I would be very interested in expanding the scope of this research in the future.

Q. If we're going to talk about shock propagation, I'm sure there are those who would want to know what we should do if there is, for example, a large-scale natural disaster or exogenous shock. Does your research have any policy implications in this area?

The finding that there is a high propagation factor in the manufacturing industry was very robust, so it is important that policies take this into account.

In the manufacturing sector in particular, there are suppliers that make very crucial components on a small scale and wholesale them all around. Policies should look at the relative impact of connections, even down to the parts that might not be noticed at that scale, and provide support accordingly.

Q. Shocks are not always bad things; there are good shocks such as innovation. We also have to consider how such shocks are propagated. Does your recent analysis have any implications for how to propagate positive shocks more strongly?

The research did not consider endogenous network formation, but I think it would be a good idea for the government to create a system that matches firms with each other. If an innovation occurs somewhere, the program could bring together firms that stand to generate significant profit from that innovation but are not yet connected to each other. I believe that this would greatly enhance the propagation effect. I think it would be very worthwhile to research the policy side of this in the future.

Future direction of research

Q. Do you have any new solutions or approaches to the issues you analyzed?

First, I would like to use exogenous shocks to analyze the causal relationships of shocks propagated in a network. What I am considering now is to expand the scope of my research, in which I would like to examine how fluctuations in sales at exporters and importers are propagated to suppliers and customers in Japan by use of data on foreign trade, exchange rate fluctuations, and so on.

Another thing I would like to do is to build a model that explicitly takes into account network formation and to examine how networks themselves change. My recent paper took networks as a given, but networks change over the medium to long term. So I think this will be a very important point going forward. The question of what kinds of firms connect with each other and how links become severed when something happens has extremely important policy implications.

Q. How are you thinking of developing this research going forward?

There are two big challenges. One is building a trade theory model that really considers inter-firm networks within Japan. The trade theory models used until now do consider the heterogeneity of firms, but they do not go as far as inter-firm networks. Quite a few international trade models have been built lately that include input-output (I-O) tables, and those are used to discuss value-added trade and indirect trade. This is exactly the kind of research we need.

However, analysis using the existing I-O tables essentially cannot distinguish between the intensive margin (an intension of trade, such as value of trade per firm) and extensive margin (an extension of trade, such as number of trading firms). The significance of building a trade theory model that accounts for inter-firm networks would be that it could explicitly handle even the network's formation and the extensive margin. It would be possible to expand the analysis to include the firm's process of deciding whether to enter a market in the first place. I would like to build a theoretical model that accounts for a firm considering whether to get involved in foreign trade in the first place, and if it does, the model should allow it to think long-term about the kinds of firms with which it will form a network.

Indirect trade is going to be very important going forward. I previously wrote a paper with you and Yukako Ono on the role that wholesalers play in indirect trade. For example, many of Toyota Motor Corporation's suppliers in Japan are small and do not engage in foreign trade, but the added value that they create is traded through the medium of a product: a Toyota vehicle. In that sense, even domestic firms are not unaffected by shocks from abroad. That is another area I would like to research.

Another research topic that I would find very interesting is to look at the dynamics of network formation. There is not a lot of data on large-scale inter-firm networks, even outside Japan. If we follow firms' life cycles from a time series and panel perspective, it is important for the sake of spotting macro fluctuations to look at the dynamics, namely, with what kinds of firms the subject firm is starting to do business, how it grows with its partners, and how it exits markets. So, I would like to continue my investigation in those two directions.

Q. What kinds of policy suggestions do you think could be derived from further research in those two directions?

For example, current foreign trade statistics can only measure direct trade, but out of all the firms in business, there are very few doing direct foreign trade—just a small percentage. However, if we expand the scope to include firms with connections to those firms doing foreign trade, the number increases greatly. Even firms that were always thought to do no foreign trade are likely to be indirectly exporting quite a bit of their value overseas. When we try to estimate the effect of trade policies such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), we have to consider the impact on those firms doing indirect trade.

If you consider inter-firm networks, then even firms that are non-exporters under the existing definition are affected by foreign risks and exchange rate fluctuations. And that impact also extends to monetary policy. The monetary policy of the Bank of Japan influences exchange rates in the short term, which results in a secondary effect, namely, changes in corporate earnings at firms that conduct foreign trade. The Nikkei Stock Average, which is compiled primarily from exporting firms, correlates strongly to the exchange rate. The effect that monetary policy has on firms doing foreign trade extends also to the partners of those firms. Therefore, even non-exporting firms would likely feel some impact, which would vary depending on their distance from the exporting firm in the supply chain. Transaction data from Tokyo Shoko Research, Ltd. (TSR) can quite explicitly track this, so I think we should be able to see the propagation effect, particularly of shocks from abroad and from monetary policy, in channels where we have not been able to see them up to now.

Moreover, I believe that research into the dynamics of transaction networks can offer suggestions to how governments should support network building. For example, a younger firm may form and sever its connections with a variety of firms because of the asymmetric nature of partner information. As time goes by, however, I predict that the quality of inter-firm matching will become clearer and stable transactional relationships will form over the long term. If there were a platform where users could share a certain amount of information, such as what firm the user should first connect itself to, it would undoubtedly be very effective at the initial matching stage. I would also like to look for implications such as a policy of lowering costs when such firms form links.

Profile

Postdoctoral Research Fellow, University of Southern California, also has been a Fellow at RIETI since 2014. His expertise includes international trade, firm dynamics and macroeconomics, supply chain and firm networks, and urban economics. His works include "Essays on International Trade Dynamics," University of Chicago Dissertation, 2014; "International Trade Dynamics with Sunk Costs and Productivity Shocks," 2014; "Determinants of Industrial Coagglomeration and Establishment-level Productivity" with Kentaro Nakajima and Yukiko Saito, 2015; and "Indirect Exports and Wholesalers: Evidence from Interfirm Transaction Network Data" with Yukako Ono and Yukiko Saito, 2016.